María Robles, like most Yaqui women, has known the open ocean since she was a child. She is one of the inhabitants of Bahía de Lobos, municipality of San Ignacio Río Muerto, Sonora, who knows what it's like to catch crab, blue shrimp and jellyfish with the fishermen in her community.

“There are very few who are involved daily in a job as fishermen... three or four women. Even so, those who work it, I don't know if out of necessity or pleasure, do a very good job,” shared María, who started collecting with her brothers when she was sixteen.

Robles, 41, studied a degree in Biology and works in the administrative area of the Yaqui Communities Cooperative. An organization of fishermen from the tribe that has 579 members. All men.

Yaqui women are not fishermen nor are they part of the Yaqui Communities Cooperative. Although for years they began to be more frequently involved in various activities, not only in the administrative area, but also in product processing and as fisherwomen, some occasional and only a couple who attend formally.

This made them protagonists in the capture of cannonball jellyfish - or aguamala, as it is commonly called in the fishing zone - on April 25.

The role of Yaqui women in fishing is indispensable. They are responsible for the hulling, gutting and packing of shrimp, tuna, crab, aguamala and others. They also subject the product to dehydration without losing its natural properties.

Despite this work, María believes that “if they were given the opportunity” more often, women might be better able to be fishermen.

“I see a lot of women who really want to dedicate themselves to fishing but the doors are half closed. They stop because of what they will say or because they don't see them as very capable. According to him, it's harder work, for men, a little heavy, but we really could be more prepared to do it if we were given the opportunity to do it freely,” he explained.

This year, the production of cannonball jellyfish, popular in the Chinese market, was 1,882 tons worth 3.2 million pesos, according to data from the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca) in Sonora. Like every season, the schools are located and extracted with a minimum size of 11 centimeters in diameter.

Due to an unfavorable climate due to heavy rains, production did not exceed that of last year. In 2020, the volume of the species was 12,369 tons with a value of 30.50 million pesos, according to the Fisheries and Aquaculture Information System (SIPesca).

Photo: Conapesca Sonora

The sea or ten hours of field

“My mom was a single mother and we worked at sea all the time since we were very young. We went to the oysters, to look for clams, one they call mule's foot. When we got home, we started taking out the oysters and selling them from jar to jar . We are seven brothers, five women and two men,” recalled Brenda Guadalupe Navarro Corona, 27.

Originally from Guásimas, municipality of Guaymas, she is also part of the Yaqui community. He says that his whole family is engaged in fishing. From her husband who has been a fisherman for a decade to her mother, who at 53 years old continues to catch clams to sell.

Fishing is the main source of income in the area. Brenda in Guásimas and María from Bahía de Lobos agreed when they answered that working at sea can have better conditions than in the maquiladora or the field where the working day lasts 10 hours, even longer.

“All day crouching, chopping pumpkin, it's really tiring,” said Brenda, who also worked in the fields.

Although Yaqui women are not part of the register, the workers of the Yaqui Communities Cooperative receive a salary for their work in whatever part of the fishing process they are located in.

An average of 350 pesos per day for the fishing season and 2,100 pesos per week for female employees in the administrative area. There is also a source of employment for them in Chinese processing plants where jellyfish, crab or shrimp are received, but these do not belong to the Cooperative.

“Yes, it's dangerous because the sea has no handle. But there are many women who cast their nets during the shrimp season, and that is heavier than the crab or the jellyfish. They go to their husbands, to their parents, to their siblings, even though it's a job for tough people. People here are very rude,” Brenda said.

“Do you think they are ready to do the same activities as men?” , he was asked. “Well the truth is, I think so,” he answered.

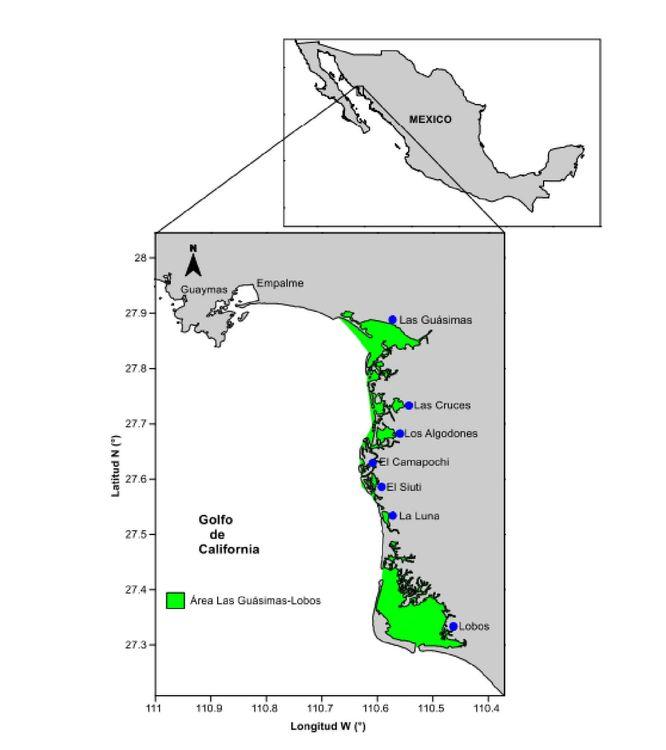

Image: “Natural Capital and Social Welfare of the Yaqui Community” from the Technological Institute

of Sonora.

The sea and household work

The Yaqui Community Cooperation agrees that the increase in women's participation is constant. Their legal representative, Samuel Valenzuela, stated that he does not deny that they continue to work in the fishing sector, however, the register continues to not register women.

“We haven't talked about including them in the work because, apart from being heavy, they are mothers of families and it's impossible for both of them (dad and mom) to go to work and leave their children at home alone... We haven't thought about it, maybe,” Valenzuela acknowledged in an interview for this publication.

María Robles and Brenda Guadalupe Navarro have different ways of dealing with the domestic.

“In my case, I take the children to my in-laws' house or to a sister of mine. She is also a hard worker and, when I can, she sends me her children. We share care,” Brenda said.

Both agreed that the problem that must continue to be solved is the machismo that is still present in the community. María believes that Yaqui women still struggle with the belief that women should only be at home: “I have struggled to defend my position at work. It's not just saying that we do things that men can't do, we also do things that men can't do. That's why I give a lot of impetus to the others: you want to go to the sea, you can, you want to do this, you can.”

Comentarios (0)