Thinking about ecosystems with their own rights is rare in Mexico, but Mayan communities in Yucatán seek to protect in this way one of their most important natural resources, the Cenotes Ring.

For at least three months ago, members of the Kanan Ts'ono'ot collective (Guardians of Cenotes, in Mayan language) began efforts to decree this ecosystem as a subject of rights, a protection scheme already used for other specific ecosystems in countries such as Colombia or New Zealand.

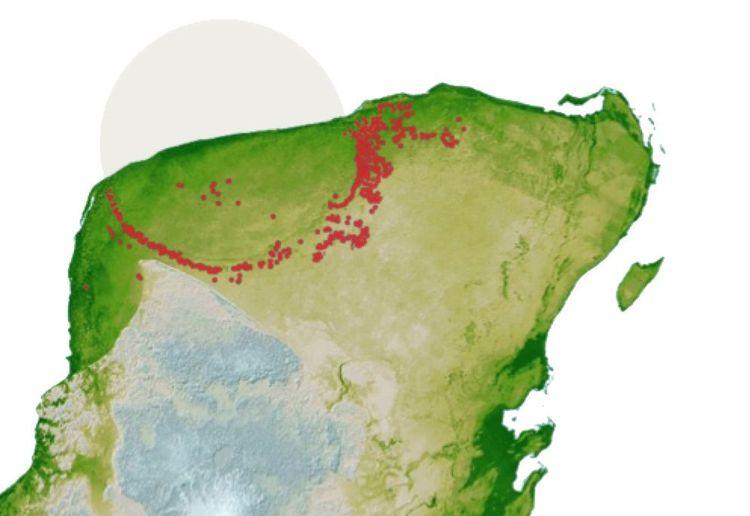

The so-called Cenote Ring is a semicircular alignment of these bodies of water, whose geological formation is related to the asteroid that produced the Chicxulub crater, possibly related to the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Image: Northwestern University

In the cenotes there is water to drink, water to clean, water to swim, and the livelihoods of the communities of the peninsula depend on them, said Clemente May Echeverria, representative of Kanan Ts'ono'ot.

This group, made up of indigenous Mayans, has been involved in a legal battle against the operation of pig farms in the region.

With a struggle of more than five years, the search for a decree that recognizes the Cenotes Ring as a subject of rights is another bet to guarantee its protection, said the activist in an interview with Journalism Causa Natura.

For May, who lives in the town of Homún, the growth of the pig industry is one of the main threats to cenotes.

“Since the cenote can't talk, it can't say anything, anyone comes and does what they want,” he said.

In the Mayan worldview, cenotes are considered sacred sites, the gateway to Xibalbá, or the underworld, a mythical place where deities such as Ah Puch, god of death, lived.

“Cenotes are very important to us and we want them to have rights: the right not to be contaminated, the right to be used with respect for our customs,” May added.

The idea of ecosystems as subjects of law is a paradigm that has been more strongly discussed in the last decade.

The Whanganui River in New Zealand, the chimpanzee Cecilia in Argentina, or the Atrato River in Colombia, are cases that respond to this trend.

In Mexico, the constitutions of Oaxaca and Mexico City already recognize the rights of nature, but not yet of specific ecosystems. If achieved, the Homún Cenote Ring would be the first ecosystem subject to rights in Mexico, explained Lourdes Medina Carrillo, lawyer for the civil organization Indignación, which provides legal advice to the Kanan Ts'ono'ot collective.

To obtain this declaration, it can be done in two ways, Medina Carrillo said. The first is with the application of reforms to the corresponding laws, where the Cenotes Ring is explicitly recognized as a subject of rights. The second is through a presidential decree, with the same recognition.

The decree initiative was submitted to governmental bodies such as the government of Yucatán, the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat), the National Water Commission (Conagua) and the Presidency of the Republic.

After three months, he said, there has been no response from any authority.

The Cenote Ring was declared a State Hydrogeological Reserve in October 2013, with an area of 219,000 hectares, but Mayan communities are asking for a stricter protection scheme, including long-term conservation plans.

In February 2022, the Foundation for Due Process submitted a supporting report on the need to classify this site as a subject of law.

The document states that regulations have been insufficient to effectively guarantee their protection, restoration and conservation.

“The alarming level of pollution faced by the Mayan aquifer due to the use of loading and discharging water for industry, the proliferation of mega-farms and the use of pesticides for agro-industry are just some of the critical consequences of the ineffectiveness of these regulations,” he says.

The pig industry in Yucatán

The town of Homún, famous among tourists for its cenotes, has been the epicenter of the fight against the pig industry.

In 2017, during a Popular Consultation process, the villagers' refusal to allow the operation of a farm owned by the Kekén company prevailed.

At the same time, a legal fight was launched that, so far, has kept activities suspended.

However, this is not the only place where dissatisfaction has been expressed. On May 17, residents of Sitilpech, also on the perimeter of the Cenotes Ring, demonstrated outside the First District Court based in Mérida, to demand the definitive closure of another farm located in this town, also owned by the Kekén company, which operates 148 throughout the country.

In the same way, residents of Sitilpech managed to suspend the operation of this farm through judicial channels, but there is still no definitive resolution.

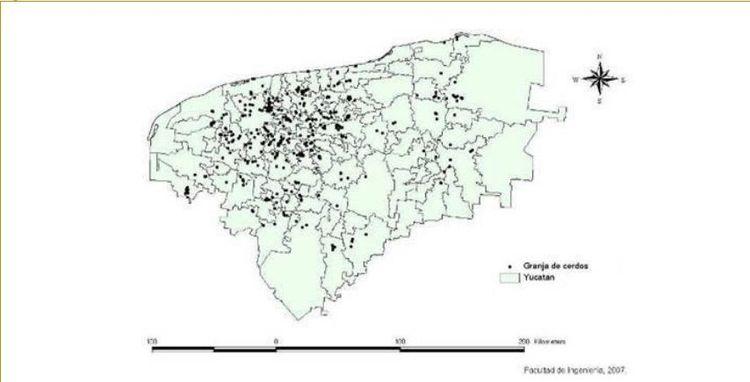

According to a report by the Mexican Institute of Water Technology (IMTA), there are 222 pig farms in Yucatán, of which only 84 have information on water management and only 18 submitted an Environmental Impact Statement (MIA). Of these, 36 are located in the Cenotes Ring area.

The contamination of pigs and poultry is one of the central points of the Regional Water Program of the Yucatan Peninsula, developed by the National Water Commission and the Basin Council.

Image: Regional Water Program of the Yucatan Peninsula

“The decomposition of animal manure causes serious environmental consequences due to the production of gases such as methane and nitrous oxide, which, in the vast majority of farms, is not collected, is released into the atmosphere. In addition, unpleasant odors and contamination of soil and water resources occur,” the program reads.

It is estimated that 631,532 kilos of excrement and more than 3 million liters of wastewater are generated daily in Yucatán, according to information provided in the Program, which is key to water policy in the area.

Gonzalo Merediz Alonso, president of the Yucatan Peninsula Basin Council, where both the environmental and agricultural sectors are represented, stated that it is necessary not to 'demonize' the industry, but to address alternatives to reduce environmental impacts.

“If it's a topic that needs to be addressed. It must be seen that those that are working illegally, who do not operate; that those who are legal but do not apply any treatment to water, should do so. It's a very important industry, which generates a lot of jobs, so we have to see how it's environmentally viable,” he added to Causa Natura Journalism.

Alejandro López Tamayo, hydrogeologist and director of the organization Centinelas del Agua, said that with the new update of the Official Mexican Standard 001, which regulates the discharge of pollutants allowed to the aquifer, there are stricter parameters.

However, he said, not all companies comply.

The specialist pointed out that cases of water pollution have been documented in communities surrounding farms, so it is necessary to apply stricter regulation.

He also expressed the opinion that although economic diversification is necessary in the peninsular region, since it is a land area sensitive to pollution and with extensive forest cover, there are economic activities that are not ideal for the area, such as the farms themselves or mining.

“If this growth of pig farms is not well regulated, then tomorrow we are not only going to suffer because of quantity, but also because of the quality of the water,” he said.

A unique ecosystem

An analysis published by the Mexican Association for Karst Studies indicates that, in addition to the fragility of the soil, the area is a temporary habitat for more than 200 migratory birds, which use cenotes for food.

Dozens of endemic freshwater fish live in the bodies of water themselves, some included in the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Culturally, cenotes also protect a large part of the archaeological remains of the Mayan civilization.

For Alejandro López Tamayo, protecting the Cenotes Ring from possible pollution threats is a priority, because he said, it is a geological and paleo-climatic record for the world, which today is being studied.

The expert in karst systems asserted that, due to its particular characteristics, the Cenote Ring could even be recognized as a geopark or a hydrogeological reserve by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

“It is possible to scale up to international protection,” he concluded.

Comentarios (0)