The advances at the Akumal fishing shelter are not black or white. They navigate on a gray scale. Six years after its establishment, researchers, fishermen and tourism staff recognize progress for the benefit of species such as turtles, corals and seagrasses. But illegal tourism and fishing practices, the omission of authorities, lack of environmental education and inadequate wastewater treatment are persistent threats.

On October 5, the agreement for the three-year extension of the Temporary Partial Fishing Refuge Zone with the name Akumal Bay, in the municipality of Tulum, Quintana Roo, was published in the Official Gazette of the Federation (DOF).

“The expansion will be to improve the functioning of the shelter. The thing is that at the same time, negative impacts have increased: sargassum, increased temperature, illegal fishing, pollutant emissions via drainage,” said Iván Penié, Research Coordinator of the Akumal Ecological Center (CEA).

The CEA is a non-profit civil association that, together with authorities, fishing and tourism cooperatives, has been working on monitoring, environmental education and training since before the establishment of the refuge. Iván Penié has been conducting research in the area since 1993.

In addition to seeking the protection of species, for six years we have been working for non-extractive tourism, the main economic activity in the area, followed by sport-recreational fishing.

“It's been difficult, but gradually people are adapting. Previously we had up to 5 thousand people inside the bay and now we are only 36 permit holders with space for 12 tourists. This has greatly improved the quality of the turtle sighting and its health. The only bad thing is that there are still groups that are not authorized and continue to carry out activities even if the authority comes forward,” said David Díaz, representative of the tourist cooperative Las Maravillas de Akumal.

The cooperative that David represents runs tours for swimming with turtles within the circuit allowed by the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas (Conanp). In turn, they work on species monitoring in conjunction with the CEA.

This new three-year term for the Akumal shelter will seek to complete the development of technical studies to define a modification in the area, says the DOF. But for those working to defend the place, this is an even greater opportunity to address threats and pending issues.

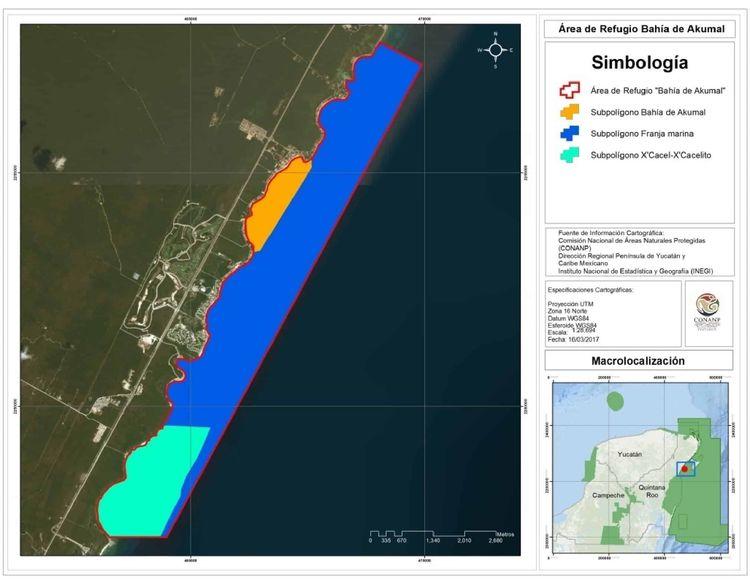

Location and delimitation of the Refuge Area for the Protection of Marine Species in Akumal Bay. Source: DOF

The big commitment to non-extractive tourism

Hundreds of tourists entering and leaving the hotels; a universe of cooperatives and tourism agencies on the coast; more than 5 thousand people waiting for the sighting of turtles. Until 2017, this was the image of Akumal Bay in a single day.

“Because of its ecological value, the low-impact tourism planning process is crucial to developing the potential of this activity as a conservation strategy in the Refuge Area,” says the Refuge Area Protection Program published in 2016.

In that document, conservation measures were established. But the emphasis is on the development of non-extractive tourism.

“The process has been gradual. A little complicated,” recalled David Díaz. During the interview with Causa Natura, he tells how the first regulation began, in which all service providers were summoned for a management plan with the installation of the shelter.

The result was the issuance of authorizations so that only 12 people per permit holder could enter Akumal Bay per day.

The reduction in the presence of 5,000 daily tourists to less than 500 contributed to the health of the green, caguama and hawksbill turtles found in the waters of Quintana Roo. For example, the Operation Wallace and UNAM Project Report: Monitoring Seagrasses and Turtles in Akumal Bay 2018 documented how the negative impact of tourists on the evasive behavior of turtles decreased. Mainly because of the cessation of interactions such as the touching of species.

“It's just that illegal or unauthorized tourist activities continue. They enter areas they shouldn't and the authority does nothing. No authority,” said David Díaz.

Source: National Commission for Protected Natural Areas (CONANP)

The problems of omission

The omission in the face of illegality is presented as a wall for progress. During the talk for the First Mesoamerican Reef System Festival (SAM) 2021 broadcast in March, the coordinator of Coastal Ecosystems of the CEA, Baruch Figueroa, broke down the problems of conservation in reef species.

“With regard to reef fish, in the last 10 years there has been a sharp decline in the abundance and biomass of major commercial species such as browns and groupers, which for more than a decade have been maintained by very low biomass levels,” said Figueroa.

The main cause is overfishing, which is mostly attributed to poaching.

During the talk, the 2020 Mesoamerican Reef Country Progress Report of the Healthy Reef for Healthy People (HRI) Initiative was also discussed, where Mexico obtained a score of 2.8 (classified as regular) but the Quitana Roo area is below this with 2.5.

“Conanp is very limited, Pofepa is practically absent and Conapesca inspectors are like three in the entire state. And the police and public security don't know the legal framework, they don't know what to do, for example, in a case of illegal fishing. Authority is practically absent,” said Iván Penié.

For Penié, it is necessary to reinforce surveillance and the legal framework in the Akumal shelter. In addition to coordinating the municipal security system. But if we talk about greater solutions, he suggests environmental education and a change in the region's development model.

“It's a disease that has a lot of symptoms, but the main one is the development model. The moment you think about increasing the number of hotels because that's how you trigger economic development, that's when you don't include the ecosystem,” he said.

Comentarios (0)