The community of Isla Magdalena, in the northwest of Baja California Sur, Mexico, has been surviving solely on fishing since 1952, but with the increase in illegal fishing, their resources began to run out, so they have undertaken community surveillance in which they have invested thousands of pesos, time and put their lives at risk to defend, rather than fishing resources, their survival in the region.

Since 15 years ago, there has been an increase in boats without permission, without registration and without cooperatives, with stolen engines and fishing for unauthorized sizes or species banned in Magdalena Bay until it became clear that fishing resources were running out.

Fishermen from the Bahía Magdalena cooperative pointed out that in 2018 illegal fishing was strengthened by the presence of groups with illegal activities and the situation became critical.

“As a cooperative you have to arrive the product, give it to the authorities and they see what and how much you get, but they don't; they grab it and sell it to the highest bidder taking whatever they find that suits them and because the resource was running out of us,” said a manager who, for security reasons, asked to protect his identity.

Although fishermen are already risking their lives every day to dedicate themselves to one of the most dangerous professions in the world, they have started to carry out surveillance work where they put their bodies and their boats to combat illegal fishing.

Organized islands against illegal fishing

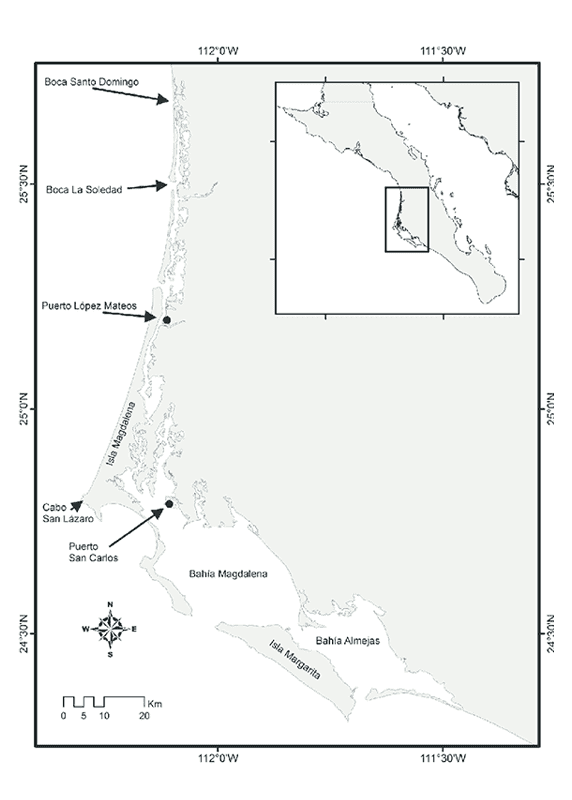

57 km from Ciudad Constitución, the municipal seat of Comondú, Baja California Sur in northwestern Mexico, is Magdalena Bay, made up of two fishing ports, San Carlos and López Mateos, and the Magdalena and Margarita Islands that protect the bay from the Pacific Ocean.

Three cooperative fishing societies coexist on the islands: Melitón Albañez, Puerto San Carlos and Magdalena Bay. The latter is based and most of its members on Magdalena Island, located 30 minutes by sea from Puerto San Carlos and is one of the oldest fishing cooperatives in Baja California Sur at 71 years old.

The National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca) is responsible for verifying compliance with regulations regarding inspection and surveillance of the fishing and aquaculture sector, but since 2009 it has only nine federal fishing officers for these tasks and in 2022 it had eight vehicles and two boats to deal with incidents in the entity.

With limited resources, Conapesca undertook 3,108 inspection and surveillance activities in 2022 focused on the North Pacific region and on dealing with illegal acts rather than on their prevention.

In the absence of presence and prevention of fishing authorities, the cooperatives organized themselves to monitor and defend the resources of those who have a concession, led by the Bahía Magdalena cooperative, because they have more members and because of their strategic position between Cabo San Lázaro and Isla Margarita and in front of Puerto San Carlos.

Surveillance increases work and risk for fishermen

Every day at nine o'clock in the evening, a group of five fishermen, including the president and secretary of surveillance, and an advisor to the Fund for the Protection of Marine Resources (Fonmar) go out on tours.

They regularly do it by sea on a cooperative boat, but when they don't have enough budget, they do it in cars on land and return until four or five in the morning to rest.

However, from November 15 to May 15, lobster season, incidents increase and complaints are heard during the day.

In the case of the president and surveillance secretary, surveillance activities are so demanding and exhausting that they have been absorbed and kept away from fishing. The position lasts two years, so there are one year and two months left before they recover their lives, their days as fishermen and also their peace of mind.

They said anonymously that they feel insecure because, given the lack of support from the authorities and social support, they and their families live in concern for their integrity and fear of being retaliated for their work.

In the last five months, the vigilantes recorded eight detentions of illegal fishing boats and last year they had a two-month streak with daily chases that mostly did not end in insurance.

The rest of the fishermen who accompany the surveillance voluntarily follow a role in which they lose at least three to six days of fishing per month by joining as a vigilante.

The guarded area ranges from Cabo San Lázaro to the Cabo Tosco Lighthouse, that is, the entire Magdalena Island and Margarita Island on the Pacific Ocean side, where the three cooperatives have concessions for lobster and abalone, the most important species in the area.

The partners agree that in the last five years to date they have received more support from the Secretariat of the Navy (Semar), Conapesca and Fonmar than from other administrations.

However, surveillance actions, precautionary detentions and complaints have decreased, this is because although there is good collaboration and willingness on the part of the authorities, most of the time the elements of Semar and Conapesca are limited in resources because they do not have enough budget, equipment and personnel to support them in their daily trips and to respond to reports.

“There is a need for more presence of the authorities at sea and for them to come and help us. With their presence, things change... Here it should be mentioned that they too need resources. Lately they don't even have boats, so it has forced us cooperatives to have our own boat and together with them to do the surveillance,” said one of them.

Conapesca inspectors are authorized to draw up administrative records in illegal fishing incidents so that a sanction process can be carried out, but since there are three based in Puerto San Carlos, without a boat and equipment they cannot attend to all the facts that are recorded.

Sources from the Bahía Magdalena cooperative pointed out that the lack of inspection and control of boats by the Captaincy of Puerto San Carlos facilitates illegal fishing, since it is from this place that most poachers are identified.

“Captaincy is the one that should take care of that but it doesn't do its job as it should. We have everything in order. We have everything the Captaincy asks for, but they only demand it from cooperatives and not from others (illegal fishermen),” said the source.

For this report, an attempt was made to interview the Captaincy of Puerto San Carlos, but they pointed out that it was necessary to send a formal request to Semar and until the close of the edition there was no response.

Routes in Homelessness

The size of the Islands is enormous and their isolation makes them a paradisiacal place with great biological wealth, but this also places them as a target of species trafficking in a large space where authority does not reach and where fishermen cannot have 24-hour surveillance.

In the last five years, the fishermen of the cooperative have experienced at least eight violent incidents during surveillance work where their teams have been shot or beaten. They have filed complaints with the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic but the investigations are not progressing.

In these cases, the greatest consequence has been the retention of the boats, but after a few days they are returned to illegal fishermen.

The insecurity they are experiencing makes them see the solution only in Semar, since even if its elements do not have the power to inspect boats, they can fight illegal armed fishermen.

The partners requested that Semar be provided with greater resources and that personnel be appointed to be stationed on Magdalena Island, as well as to improve the operation of Conapesca and the Port Authority so that the inspection and control of improper vessels be applied.

The sustainability of surveillance

To sustain surveillance, the cooperative has been supported by Fonmar, a trust created by the government of the state of Baja California Sur to manage income from sport fishing, which provides them with 200 to 400 liters of gasoline per month.

However, the rest of the expenses, which on average amount to one and a half million pesos per year, are borne by cooperatives.

They recently purchased “The Beast II”, a boat with two engines worth 790,000 pesos to improve surveillance. This one has greater capacity and speed than the previous one they had and gives them the possibility of not neglecting the area in case one breaks down.

Even with the two boats, those in charge of surveillance pointed out that it is not enough, since they have faced groups of up to seven boats and it is impossible to chase them all to deter them.

Those in charge of surveillance receive a weekly salary from the cooperative that helps them meet their needs, however, they pointed out that it is not enough for all the work they do and the risks they face, but at the same time they face the challenge of determining what is the value of the work they do and who should be the one who should bear these costs.

The Golden Link

Any community effort to protect resources and extract them in a sustainable way would not be possible without the commercialization of cooperative production. It is the marketers who demand legal products and those who motivate cooperatives to comply with regulations and generate income for them to survive.

Jorge Chávez has been working with the cooperative since 1992 and exports all his lobster, abalone and axe callus production to Asia and other destinations in Mexico.

In the end, the resources they invest in surveillance to pay salaries, buy boats, equip them and gasoline come from the profits generated by their productions and, in turn, this effort is rewarded by being purchased at good prices in an international market.

In part, this is the result of Jorge's work to make his customers aware of the importance of consuming seafood that are legal and of encouraging fishermen to become certified and to remain within the law in order to continue exporting their products to other countries.

Fishermen insist on overcoming the challenges of implementing sustainable fishing, even if they are currently doing so aboard The Beast II chasing some illegal vessel that tries to flee after being discovered extracting lobster during the ban.

For now, this is what they can do, said one of them, and what has worked for them to ensure their livelihood on the island, while they wait for their demands to be echoed by the authorities and the surrounding communities where illegal fishing comes from.

Comentarios (0)