On the night of September 6, the streets of Tula, Hidalgo, were covered with rain and sewage from the Valley of Mexico. The flood after the river overflowed damaged 31,000 homes, left more than 70,000 people injured and caused the death of 14 patients with Covid-19 hospitalized in a hospital of the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS).

To remedy this, the National Water Commission (Conagua) designed a Water Plan that recently began its second phase of works to expand and cover the Tula River. However, it is the victims themselves, as well as environmental groups in the region, who are opposed to this project.

“They are not solving the underlying problem,” summarizes Violeta Arellano, a resident of the San Miguel Vindho community in Tula de Allende, and a member of the We Want to Live Environmental Awareness Network.

“If Mexico City, the Valley of Mexico, needs to expel all that water so as not to flood, they chose the easy way, which is to use the riverbed, make it bigger, fill it with cement, turn it into a channel and that we receive everything...”, he described.

According to information presented by Conagua at meetings with environmentalists and neighbors, the Tula de Allende Water Plan is divided into four actions: desazolve - which consists of cleaning drains - and the expansion of the river in two stages; the development of a protocol for the rainy season; the creation of a network of automatic measurement stations in the basin and, finally, the rectification of the channel and its concrete coating.

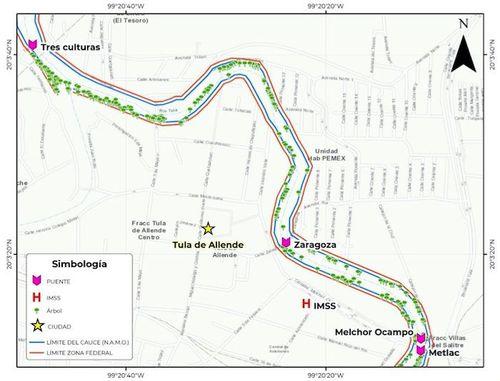

In the process, around 230 trees will be felled, 80 buildings are planned to be demolished and works will be carried out to raise the Metlac, Melchor Ocampo, Zaragoza and Tres Cultura bridges.

For the latter reason, in mid-April, citizen complaints about loss of roads and space for micro businesses were heard. A demonstration was also held by the Great Assembly of Victims of Tula, formed since the end of September 2021 by those affected by the flood.

The objective of all these modifications, as indicated by federal and state authorities, is to increase the volume of river reception to prevent flooding. What for the inhabitants of Tula means expanding, felling and cementing the riverbed in order to receive more sewage from the Valley of Mexico.

Conagua itself has estimated that capacity will more than double, from 230 cubic meters per second to 677. An equivalent to 677 thousand liters per second, above the more than 500 that were reached early in the morning of the overflow.

“To avoid floods in Mexico City, all they do is transfer (water) to an area where we have less than 200,000 inhabitants compared to more than 100 million there. But in the end, our lives are worth the same as those who live in Mexico City. Why bring us the problem, why not make their own channel,” Arellano questioned.

Although the mobilizations to redesign the Water Plan have generated a couple of meetings and working groups with the state Conagua, groups such as the Environmental Awareness Network We Want to Live or the Great Assembly of Victims of Tula stated in an interview that they have not received the expected response nor have they been considered in the design proposals.

Tree felling contemplated for the Tula de Allende Water Plan. Source: Conagua (image provided by the Environmental Awareness Network We Want to Live).

Tree felling contemplated for the Tula de Allende Water Plan. Source: Conagua (image provided by the Environmental Awareness Network We Want to Live).

Anticipated flooding

After the flood in Tula, it took two months for federal authorities to recognize that the heavy rains that night in September were not the only cause of the disaster.

On November 15, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador mentioned during his morning press conference that Conagua would publish an opinion explaining what had happened. It recognized for the first time the ravages of discharges from the Valley of Mexico.

“In the early morning of Tuesday, September 7, the estimated flow that traveled through this river was of the order of 500 m³/s (cubic meters per second), of which 150 m³/s came from discharges from the Valley of Mexico through the Emisor Central and Emisor Oriente tunnels, 28 m³/s from the El Salto river, 100 m³/s from the discharge of the Requena dam, 130 m³/s from the Tlautla River, and 92 m³/s from the proper basin between the exit of the tunnels and the city of Tula de Allende describes”, the document delivered at a working meeting in Tula and obtained through the Platform of Transparency for this publication.

In addition, since previous days, heavy rains have collapsed the municipal drainage of Ecatepec and the overflow of the Chimalhuacán drain, in the State of Mexico, occurred.

The Commission also admitted that the Tula River did not have the expansion works ordered by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) in 2016, prior to the entry into operation of the Eastern Emitter Tunnel (TEO), a 62-kilometer-long hydraulic project that had been built since 2008 with the purpose of helping to increase drainage capacity.

However, the ruling also identified environmental groups in the region as responsible for preventing the works of the TEO.

“In 2017, we opposed it because the project considered the destruction of the river's ecosystem by felling more than 9,000 trees, most of them centuries-old, such as ahuehuete trees... The objective was to get more water from the TEO (from the Valley of Mexico to Tula), even though we already had pollution from the Central Emitter Tunnel...”, explained René Romero, part of the collective Communities in Defense of Life and Territory of the Tolteca Region.

The protests of that time led to meetings with Conagua to redesign the plan without affecting the environment. But after the end of Enrique Peña Nieto's six-year term, only one of the five planned stages was completed and there was no further progress.

“The main slogans were 'Not one more tree' and 'No to the discharge of the Eastern Emitter Tunnel into the Tula River', because this represents an additional volume that could bring flooding,” Romero added.

It was until 2019 that President López Obrador inaugurated the TEO without completing the first works ordered by Semarnat. This completed the plan for the Valley of Mexico and the Mezquital Valley, in Hidalgo, to be interconnected as part of the same Deep Drainage System.

Specialists told The Washington Post that the flood in Tula could have been prevented if the floodgates of the drainage system had been closed until river levels dropped, but this would have caused Mexico City to be flooded.

“We learned that the works (of the TEO) were stopped by groups of environmentalists who opposed the felling of trees. A lot of people unaware of this project didn't get involved until after the flood,” said Berenice Pecina, president of the Tula Grand Assembly of Victims.

During the interview, Berenice describes that she began to enter when she and her family were affected by the flood on Moctezuma Street.

Currently, the Grand Assembly, which began with 10 representatives, has 70 of more than 20 affected streets, such as Leandro Valle, Moctezuma, Heroes of Chapultepec, Toltecs, Heroic Military College, Callejón Club de Leones, Three Cultures, La Carrera, Pueblo Nuevo, San Lorenzo, San Marcos and Vuelta del Rio.

“As a group of victims and with the support of all the organizations, even the same environmentalists who had previously done the work of getting involved in the initial project, we came to the conclusion that we do want the Tula River to be cleaned, but we don't want rectification or cementing. The stretch where it was cemented last time was also flooded because the drains are very low, at floor level,” Pecina explained.

Both affected people and environmentalists agree that the solution partially addresses the problem. The efforts of the Conagua Water Plan are focusing on the downtown area of Tula, leaving aside the 12 municipalities through which the riverbed crosses.

In addition to this, the more than 70,000 people affected by the flood have not yet obtained reparation for the damage.

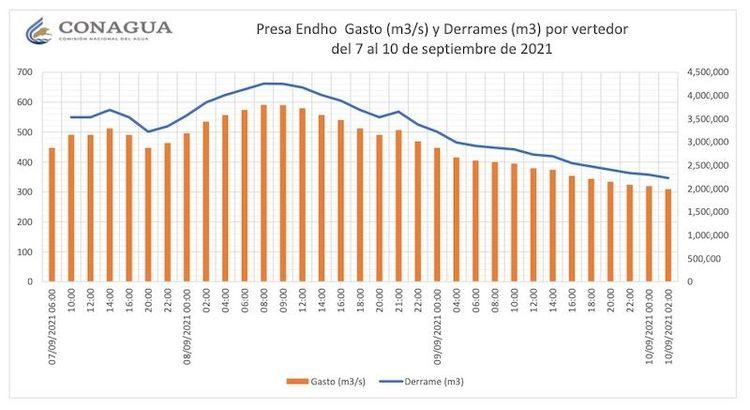

Expenses and spills per cubic meter in the Endhó dam, located downstream of the city of Tula de Allende, responsible for receiving discharges from the Tula River. Obtained via a transparency request.

Expenses and spills per cubic meter in the Endhó dam, located downstream of the city of Tula de Allende, responsible for receiving discharges from the Tula River. Obtained via a transparency request.

No response to solutions

In 2005, the United Nations considered Tula to be one of the most polluted regions in the world. Since that year, the Hidalgo dams, such as the Endhó dam, which receives discharges from the river, have been classified by the media as the largest latrine in the world. Label with which the inhabitants of the municipality agree.

Residents of the region live with the smell of putrefaction that emanates from sewage from Mexico City and extends around the river.

Beatriz Rodríguez Díaz, PhD in Science from the National Polytechnic Institute, has been involved since the first demonstrations at the 2017 works with the Environmental Awareness Network, mainly in the community of San Miguel Vindho, to document and advise a thesis on the environmental impact of discharges.

“The expansion of the Tula riverbed for many years, out of interest and anthropogenic action, affects air, soil and water. Currently, vegetation has been considerably reduced... in addition to having arid and non-arable soils that harm the inhabitants of the town...”, details the research.

Added to this are the pollutants from the Cruz Azul cement plants and the Petroleos Mexicanos refinery (Pemex), which are also active in the area.

The Tula de Allende Water Plan does not mention any of the impacts that already exist on the river. Nor are there actions focused on preventing environmental damage.

“They are solving the problem of Mexico City, no one is ever thinking about us,” said Violeta Arellano.

As part of the common solutions proposed by environmental defenders, affected people and specialists involved, it is to focus on the source of the problem: Mexico City.

For this, it will be necessary to restore the regulatory vessels that allow water to be retained. This includes the removal of the Requena dam, located on the Tepeji River for discharge to the Tula River, and the Endhó dam. But also others such as the Tacubaya dam, which is currently in the middle of the works where the Mexico-Toluca Train will be carried out.

“Conagua tells us that the projects we are asking for are very expensive. But rather there is no political will to do something more sustainable,” added Berenice Pecina of the Network of Victims.

Both groups report that they will take regional demonstrations to other federal bodies for a response. Even if Conagua's work to expand the Tula River continues, the defense will not stop, they said.

Comentarios (0)