The conflict between Sinaloa's 16 fishing cooperatives ended. For more than two decades, coastal fishermen in the El Caimanero area, municipality of El Rosario, remained in dispute over the use of prohibited fishing gear and access to some areas of the place. The solution became an agreement signed on September 28 in the Sinaloa Congress. Now, the pending issue has another name: dredged.

Iván Teodoro García, president of the General Álvaro Obregón cooperative, and Primitivo Deras Gómez, president of the Greenwater Shrimp Federation, both longtime fishermen and representatives of two of the parties involved in the agreement, hope that it will address the problems. But while what was signed is reviewed before a notary and a copy is given to the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca), the resolution of the conflict highlights the common problems.

According to the fishermen, there is a lack of dredging to improve fishing activity in the region. These are cleaning processes in which rocks and sediments are removed in bodies of water such as canals, lagoons and rivers.

“We have always commented on the lack of support from the authorities for dredging. The federal government took away the supports (subsidies) we had... but what we do ask of it a lot is that we don't forget the dredging of the Caimanero lagoon,” said Primitivo Deras Gómez.

The request for dredging raises questions in the environmental sector. “It depends on the area, but dredges usually suspend sediments that can be carried by currents and are deposited on other marine organisms,” explained Alejandro Olivera, representative in Mexico of the Center for Biological Diversity.

In an interview, Olivera suggests that research be carried out considering the particular characteristics of the Huizache-Caimanero coastal lagoon, an area that in recent years has gone from an exemplary fishing activity throughout the Pacific to being a place of deterioration.

Dredging work in 2014 for the Humaya and Tamazula rivers, in Sinaloa. The reason was the heavy rains to prevent future floods. Photo: Rashide Cold/Darkroom

A hole in the water: dredging and the agreement

The Huizache-Caimanero lagoon was one of the most productive shrimp areas in the Pacific. In 2005, the area was designated as a Ramsar wetland of international importance.

Although it remains the area of main economic activity, the modification of the hydrodynamics of the lagoons generated sedimentation, death of species, erosion and loss of mangroves, according to the Network for Sustainable Development Solutions (SDSN) of the United Nations (UN) in Mexico.

The changes in land use and the works to connect a beach mouth brought the entry of sediment into the area, that is, flooding. In turn, this prevents proper navigation and species development.

The production, which in a single night allowed the collection of 32 tons of shrimp, is currently a volume that is not seen in the entire lagoon during the fishing season.

To these effects were added the bad practices resulting from the cooperative conflict, mainly due to the use of prohibited arts such as pens and chacuacos, as well as the use of purine (an attractive food for shrimp), which increases the mortality of what is caught.

“There are many factors for improvement. But I do emphasize that internal dredging in the lagoon can be beneficial to everyone: more product would enter the marshes, there would be bright tides and salinity levels would fall,” insisted Iván Teodoro García, president of the General Álvaro Obregón cooperative.

“They would help us because the marsh is flooded and channels are needed to hold water. Because if the level is low, it heats up and the product dies,” added Primitivo Deras.

However, from the environmental sector, dredging does not always represent a solution. On several occasions they can cause problems to the environment, such as the Don Diego underwater mine, in the Gulf of Ulloa in Baja California Sur, where the American company Odyssey Marine Exploration wanted to extract phosphorus from the seabed by dredging.

“But it's not that easy. It's not dredging here and dredging there. Research is needed to know the dynamics of currents, where they could and under what circumstances. They (the fishermen) will need to submit an Environmental Impact Statement (MIA),” proposed Alejandro Olivera.

The MIA is a technical-scientific study that allows us to know the effects that a work or activity may cause on the ecosystem, which is submitted to the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat).

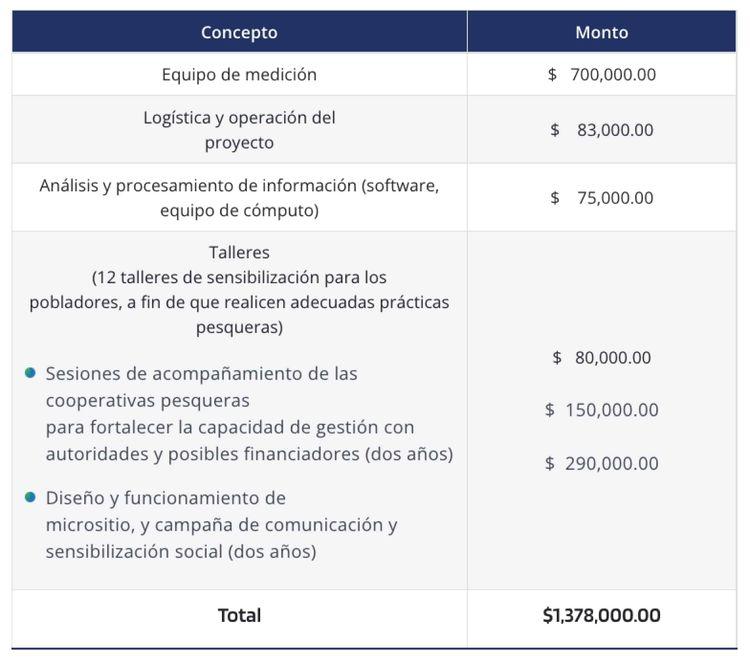

For its part, the UN SDSN also believes that to restore the Huizache-Caimanero lagoon system, it will be necessary to work on research that includes better fishing practices, management, conservation and adaptation. The site even breaks down the costs of an improvement project.

Support and costs of the progressive restoration plan for the Huizache Caimanero lagoon proposed by the SDSN.

On hold: the costs and what is pending

While common petitions exist in cooperatives in southern Sinaloa, solutions to their differences take a new direction.

“It is agreed not to throw purine; not clogs across the width of the marsh; and the concession of cooperatives will work together for all the cooperatives in Laguna del Caimanero. It is also agreed not to increase the fishing effort required by concessions,” says the agreement signed at the Sinaloa Congress.

In the case of the use of illegal fishing gear, the cooperatives established penalties of 20,000 pesos. In addition, they will work together for inspection and surveillance rounds, whose costs are borne by fishermen.

For its part, the Álvaro Obregón General Cooperative covers needs to improve activity in the area, such as labor, operation of fishing sites and offices in general. An estimated 600,000 to 700,000 pesos a year, of which loans are obtained from March until the end of the season.

“I want them to be aware of the expense we make to really cover everything, not just the cooperative, the whole town. Everything we had for the benefit, with the agreement, they left us at bay, but what we don't want is for there to be a conflict,” said fisherman Iván García.

The cooperatives belonging to the Green Water Shrimp Federation coordinated by Primitivo Deras recognize the economic effort of their fishing companions. And they hope that by the next fishing season, the needs in the Huizache-Caimanero del Rosario lagoon, Sinaloa, will no longer be excluded from state and federal action.

Comentarios (0)