Only 16% of 37 different elements in the area of fisheries transparency showed extensive progress between 2021 and 2023; 42%, partial advances; and another 42%, zero progress, according to a follow-up to the fishing evaluation of Taking Stock 2021, prepared by the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (FiTI), in collaboration with Causa Natura Center.

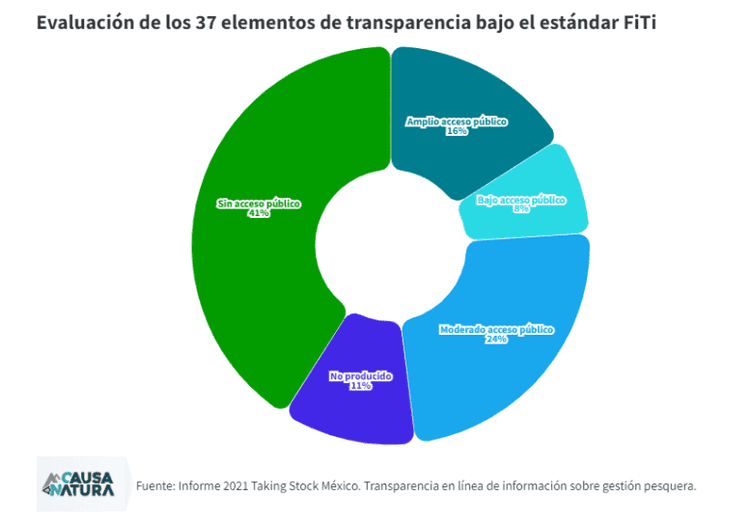

Two years ago, this evaluation showed that with regard to public access to fisheries information, only 48% of the total elements evaluated were public, at different levels of quality.

“Some in total transparency, but others in medium or little transparency,” explained Harumi Hayashida, coordinator of the Applied Research Unit at Causa Natura Center.

The FiTI standard is an international framework that defines what information on fisheries management should be published by national authorities and assesses whether it is freely available, updated and findable.

In 2021, only 16% of the elements evaluated were widely available to the public, in accordance with the FiTI standard. Mostly information regarding issues related to the capture and disembarkation of larger-scale vessels.

For its part, 41% of the elements evaluated had evidence of their existence without being public and of 11% of the total there was no evidence that this information was being recorded, so the FiTI made a series of recommendations to the Mexican government.

Among the main ones were making public information that existed but was not available for consultation, addressing information gaps and ensuring that public information was systematized and easily accessible.

Two years after this report, Causa Natura Center evaluated the implementation of these recommendations and identified that there are “total” advances in 16% of the 37 elements evaluated, mainly with respect to databases of notices of the arrival of larger and smaller vessels and the disembarkation of larger-scale vessels in ports in Mexico.

42% of the elements have partial advances. These include aspects such as: fishery resource states, development projects, employment information and payments for fishing of large scale vessels.

“Although information is published on the payments that both larger and smaller vessels must make, this information is not disaggregated at the vessel level. Information was also found in the INEGI on employment issues, but these reports are for 2018, they are out of date,” said Hayashida.

Finally, 42% of the remaining elements show no progress. These are evaluations of information on foreign vessels that fish in domestic waters, Mexican vessels that fish in third countries' waters on the high seas, transshipments, the application of labor standards, information on penalties for crimes and discards, and information on final beneficiaries in the fishing sector, Hayashida said.

Satellite data

Mexico has made progress in terms of fisheries transparency in this six-year period, such as the publication of satellite monitoring data for larger vessels by the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca), something unprecedented, but accessibility to these data still needs to be improved, according to Mariana Aziz, director of transparency campaigns at Oceana.

“What the Mexican Government has done so far is to upload databases in excel sheets with the geographical location of the vessels, which doesn't tell us anything if there is no subsequent analysis,” Aziz said during the webinar Opportunities and Challenges of Fisheries Transparency in the Current Administration, organized by Causa Natura Center.

Oceana has uploaded these databases to Global Fishing Watch, an open data and analysis platform where people can visualize the trajectories of boats on a map and make it more visual.

The location of the vessels is managed by Conapesca and Semar also has access to the data, with two main purposes, Aziz points out, one is to have the location to deal with safety issues such as accidents on the high seas, and the second is to detect illegal activity such as illegal fishing.

“So this information allows us to know if fishing vessels are complying with this regulation or not,” Aziz explained.

Challenges

One of the irregularities detected is that government sources that generate information on fishing such as Conapesca, INEGI and the Ministry of Economy present data that are not coincidental and this generates confusion.

The lack of information causes an underreporting of production, demonstrating that there is no control over fishing effort and that there are no incentives for legal fishing. At the same time, the level of occupational vulnerability in which fishermen find themselves is unknown.

“Without this data, it is not possible to drive this activity (fishing) towards sustainability,” said Hayashida.

Transparency is currently in an adverse context because the current administration has not encouraged it, so for the researcher at Causa Natura Center, it is necessary to fill the information gaps and that in the next administration the recommendations of the FiTI be resumed so that transparency can have a greater impetus.

Comentarios (0)