In Mexico, fracking is only stopped at the president's word. Since the beginning of his six-year term, Andrés Manuel López Obrador included as number 75 of his 100 government commitments to curb this hydrocarbon extraction technique. A demand that has been driven by specialists and civil organizations due to impacts on the environment and health.

However, months before the elections for the presidential change, there are eight initiatives for the ban, proposed by different benches, that have not been ruled out, according to the legislative monitoring carried out by the Mexican Alliance against Fracking, made up of more than 40 groups in the country that are taking actions to stop this practice.

While the review is postponed, the president's word is the only thing keeping activity in unconventional wells limited. But the lack of legal support has allowed Petrleos Mexicanos (Pemex) and institutions such as the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH) and the Security, Energy and Environment Agency (ASEA) not to curb the practice from their different powers. This has had an impact on the fact that a budget for fracking is granted and exercised throughout this six-year period.

Even so, in his fifth government report, released from Campeche last September, President Obrador mentioned as one of his achievements that fracking is no longer practiced. A statement that was questioned because although tenders have been canceled, existing wells continue to operate in states such as Tamaulipas, Veracruz and Puebla, in the east of the country, where the effects are already visible.

Wells in the mountains

In the ejido of El Tablón, the first thing to alert them was a penetrating scent. As it is a region where there are wells for the extraction of hydrocarbons, its almost 300 inhabitants live with the constant smells of gasoline and gas, but this one was different and came from a well called Pankiwi intended for fracking.

“This well (Pankiwi) was established on land that is not in El Tablón, but belongs to the community of Ameluca, which is less than a kilometer away. (The exploration) began in 2018, but one thought it was one more well among the many that are nearby,” Guadalupe Pérez, a resident of the ejido, said in an interview.

El Tablón is the last community in the municipality of Pantepec, on the border with the municipalities of Venustiano Carranza and Francisco Z. Mena, in the northwestern highlands of Puebla. It is a rural region where native peoples prevail and languages such as Totonaco, Tepehua and Otomí are spoken. There are also livestock territories that are known as “small properties”, and it is in most of these that oil wells are installed or infrastructure pipelines pass through.

In Pantepec, extraction began in the 1970s, when Pemex established an oil well in the El Tablón ejido. And fracking, also called hydraulic fracturing or hydrofracturing, became popular in the 90s.

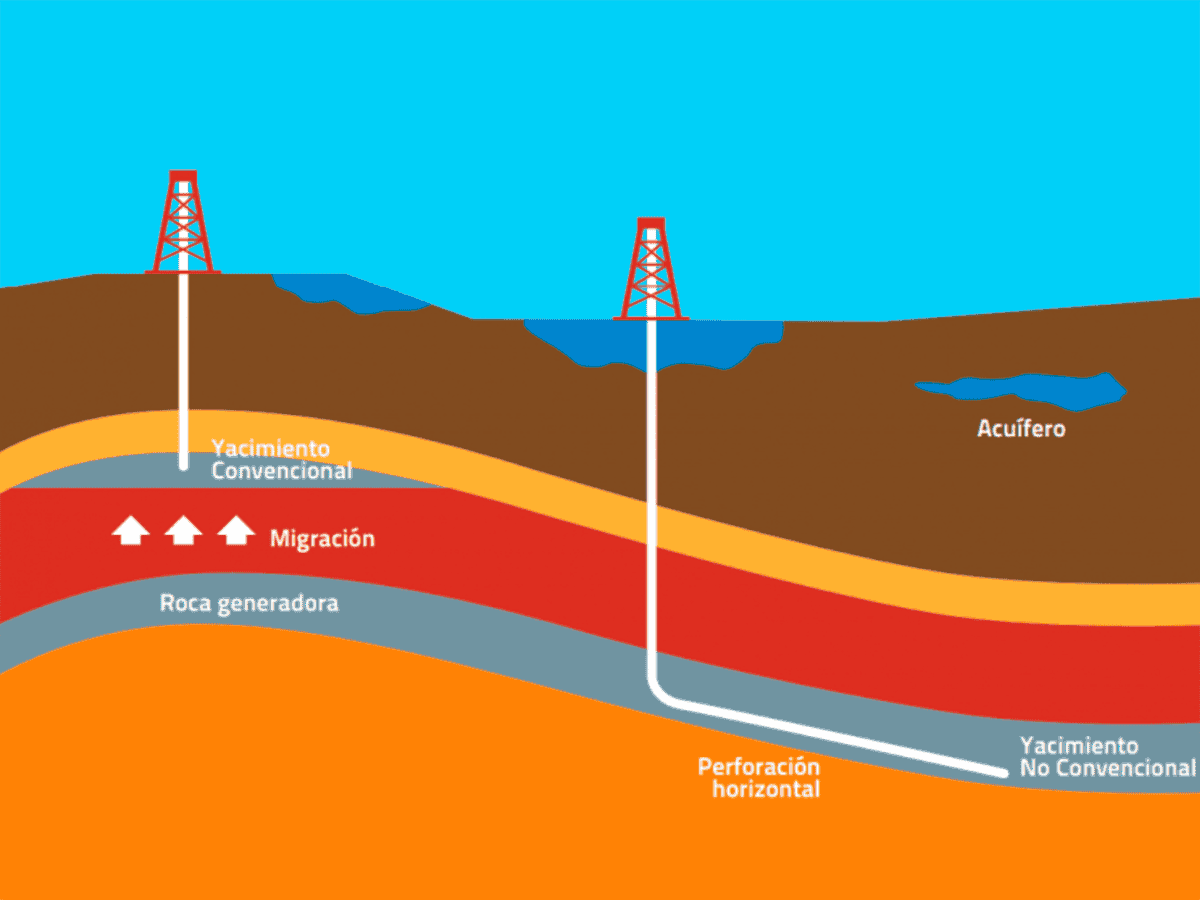

Fracking is a technique for obtaining gas or oil from the subsoil by breaking up rock bodies that are injected with water under high pressure, among other chemicals. In countries such as Mexico, Argentina and the United States, it has been possible to document that the fracturing of a single well requires between 9 and 29 thousand cubic meters of water, equivalent to between two and seven Olympic pools. This has been one of the main characteristics in raising questions: the use and pollution of water.

In the conventional manner, borehole drilling is vertical. However, in the face of the depletion of traditional deposits, what is sought with fracking is to fracture the bedrock where the poor permeability allows some oil and gas residues to accumulate. It is these unconventional wells where President López Obrador focused his speech in favor of the ban.

Guadalupe Pérez, who has witnessed years of drilling in the Sierra de Puebla, pauses to review how many wells are still active in the El Tablón region alone. It concludes that there are five, including Pankiwi for fracking, which, in turn, is part of the “Gulf Tertiary Oil” project, with official records since 2006.

In a documentary made by the Mexican Alliance against Fracking, together with the organization Earthworks, it was demonstrated that there are 1,337 wells that have been exploited for more than a decade in states such as Puebla and Veracruz where these projects have operated. Many are abandoned or unsealed. Of the total, 233 are estimated to be fracking. Regarding the Pankiwi well, it has been demonstrated that in 2019 it fractured up to 15 times.

This documentary shows that the practice allows the release of methane and other volatile toxic gases such as benzene, toluene, ethane and propane, which have health impacts and destroy the ozone layer.

In addition, the release of gases from fracking has been investigated in other studies, such as the Compendium of Scientific, Medical and Media Findings Demonstrating the Risks and Harms of Fracking, prepared by the Concerned Health Professionals of New York, which links air pollution with respiratory diseases such as cough, asthma, irritation, and others such as premature deaths and the risk of cancer. Conditions that have become common among the inhabitants of communities such as El Tablón and that have led community and ejido authorities, as well as their inhabitants, to initiate a series of legal and public lawsuits in recent years to address the effects, whether or not there is a ban.

Money to fracture

The Sierra Norte de Puebla isn't the only place in Mexico where the presidential word hasn't stopped fracking. Another of the best-known cases is the Tampico - Misantla basin, between Tamaulipas and Veracruz, with an area of more than 57,000 square kilometers and a plan for 10,470 wells, in which President Andrés Manuel López Obrador called for the cancellation of tenders at the beginning of his administration in 2018.

In 2019, the Mexican Alliance reported that under the argument of a new exploration strategy for unconventional deposits, the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH) authorized Pemex to explore fracking wells for the Tampico - Misantla basin.

President Obrador's response was to argue that this project had not been authorized and that Pemex had already received the corresponding instructions. But according to an official CNH report, in 2019 Pemex drilled four exploration wells “for unconventional objectives”, of which two were oil and gas producers in the Pimienta Formation and one was an oil and gas producer in the Santiago Formation in Tampico - Misantla.

“If you don't make a legal change, the obligated bodies in the country that have to do with the matter have no instrument not to allow it. If Pemex introduces a work plan that involves the use of fracking, the National Hydrocarbons Commission has no elements to deny that work plan because there is no legal basis to say that this is no longer valid,” explained Claudia Campero, geographer and member of the Mexican Alliance against Fracking.

In addition, throughout this six-year term, Pemex has been one of the most executive-backed companies in the State. This has also led to the maintenance of allocations in the Federal Expenditure Budget. From 2018 to the 2024 allocation, more than 60 million pesos (3,560.957 USD) have been allocated to projects involving fracking. In a more detailed analysis, the Mexican Alliance has a follow-up in which it has documented that the federal government grants between 4 and 16 billion pesos per year.

One of the positive points is that the amount exercised has remained below 7 billion throughout this six-year period. Even for 2024, the allocation was reduced by 4.63 million pesos, which represents 50% less than in 2023.

Regarding the most recent actions, on December 1, organizations and communities that make up the Alliance demonstrated in front of the National Palace to remind the president that there were 305 days left until the end of his term of office and to demand that a moratorium be established in the national territory with respect to this practice. At press time of this report, the federal government had not issued a response.

Fracking yes, fracking no

Burning eyes and throat, dizziness and vomiting are some of the ailments experienced by those who live in the ejido of El Tablón, in Puebla, and which several of its inhabitants attribute to decades of being in a region dedicated to the extraction of oil and gas, both by traditional means and by fracking.

The changes are not only visible in their health, exploration for fracturing has involved dynamiting the Earth. This leaves it unproductive, at the same time causing other consequences such as displacements and small earthquakes.

Guadalupe Pérez remembers that with the beginning of the concessions, a type of machinery with sensors arrived, whose activity caused houses to be shaken, resulting in several homes with cracks. Not only homes, but also mostly dirt roads have been damaged by the weight of pipes, machines and other heavy vehicles that travel constantly. There is even a part of the route that is colloquially known as “the swing”, since the movement of the earth has caused a subsidence.

To address the effects, a mobilization began in El Tablón in which the intervention of Pemex was requested, as well as the private companies responsible for developing the projects. The response, residents point out, was a refusal in which the different actors justified not having responsibility, assuring that it was the responsibility of the other, not theirs.

“Something similar also happens with the municipal authority (of Pantepec) because Pemex has said that it provides resources to the municipality, but we don't see them reflected for the benefit of the communities, specifically in El Tablón,” said Guadalupe.

As far as they know, when Pemex contributes directly to communities, it does so with school repairs, such as painting fences or donating material for work. The lack of attention to the rest of the inhabitants led to a complaint in 2019 to the National Human Rights Commission. This indicated that from its powers it could only make a call to ASEA, responsible for regulating and supervising energy activity in the country, but it did not go far enough. “Even so, we recognize it as a pressure mechanism,” Pérez says.

Another worrying change in the community of El Tablón is that the influx of the El Caliche spring that is available for supply has decreased. In Mexico, as well as in other Latin American countries, those who oppose the ban on fracking point out that the practice should be regulated to occur in regions with greater water availability. There are even those who say that excessive use is not necessary and that a treatment effective enough to reuse water can be given.

“Among the myths of fracking or hydraulic stimulation is the excessive use of water. But actually the return of water can be greater than 50 percent and this resource can be reused. When the application of fracking is completed, water returns are generated. Its volumes vary depending on the type of reservoir,” said the Colombian Oil and Gas Association.

However, international organizations have documented that the use can reach up to 29 million liters. Luca Ferrari, a researcher at the Geosciences Center of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, points out that the process that brings water to fracking makes it difficult for it to have another treatment.

“It's usually left in large pools and then transported to other wells. In Mexico they are called latrine wells. The liquid (used) can be injected there and is expected not to contaminate, however contamination has sometimes occurred even in the fracking operation itself. If the well is not well sealed, the water and its chemicals may leak and contaminate the aquifer or there may be a deeper fracture that carries this contaminated water upwards,” said researcher Ferrari.

The existence of latrine wells does not mean that there are no cases in which treated water is reused. In California, United States, the water used is reused for irrigation. This led to an argument in 2022 for the state to ban farmers from farming with this water.

“In fracking, permeability is artificially induced in order to remove some of this oil and gas that is left between the rocks, but it's really very little, actually 15% of what's there is out there,” the researcher explained.

For Ferrari, the costs are higher than its profit. “We are in a period of decline in the amount of energy available through hydrocarbons. Not only from an environmental point of view is there an awareness that we can no longer use them, but also because they are finite resources and over time it is increasingly difficult to extract oil and gas. Instead of following the idea of growing that production, we should be using what's left in a very parsimonious way to prepare for a society without fossil fuels,” Ferrari concluded.

New law and another presidency

The General Water Act is currently being discussed in the Senate, a legislation that has also been pending for 10 years, and is accompanied by a citizen initiative called Water for All that seeks to prioritize human rights in supply.

“This citizen initiative includes in its articles that water is not allowed to be used for fracking. Fracking is not discussed because it is not a law that talks about the extraction of hydrocarbons, but it has a practical effect,” Campero explained.

Although it has not yet been put to a vote, the initiative is in the committees. Only that there has been a modification to the article in which it is intended to point out that water for fracturing that is classified for domestic or agricultural use should not be used, which only protects these two types of use, but still leaves everything in what is classified as industrial use.

While the law is being revised, the country is less than half a year away from voting for a new president.

For their part, communities such as El Tablón point out that, beyond what is legal, there is still work to strengthen their region. “The work has to be done in territory, in communities,” insists Guadalupe Pérez, who believes that external support and prohibition laws are important, but they are not the final objective. “We have to try to make sure that roads can take us where we want to go.”

This text was produced with the support of Climate Tracker Latin America

Comentarios (0)