The specter of a possible commercial embargo on Mexican fisheries haunts Mexican fishing and trading communities. It would be the first time in President Joe Biden's administration to ban fish and seafood from Mexico from entering U.S. territory.

Now, under the Pelly Amendment, the United States government has certified Mexico as a country that violates international treaties that protect wildlife. From then on, it has 60 days, that is, until July 17, to determine possible trade sanctions against Mexico.

“And it all stems from the fact that Mexico has not been able to demonstrate that they are protecting the vaquita (the most important endemic marine mammal in Mexico),” said Alejandro Olivera, representative in Mexico of the Center for Biological Diversity.

But according to Enrique Sanjurjo, executive director of Pesca ABC, an organization dedicated to sustainable fishing in the port of La Vaquita, San Felipe, Baja California, these embargo measures have worked the other way around; they open up new markets to illegally trade embargoed species.

Despite a long history of preventing the extinction of the marine vaquita that dates back to 1975 with the total ban (prohibition of fishing) for totoaba in waters of the Gulf of California, the Mexican government's plans have been insufficient and it is on the verge of extinction, Olivera said.

In the Upper Gulf, poaching continues for totoaba, a banned species with high value in China and for which the vaquita has been accidentally fished in the past; the habitat of the vaquita is not respected and the presence of gill nets (which, like other nets, become ghosts when abandoned in the sea), deadly actions for the species, continues.

Embargo closes sustainable fishing markets

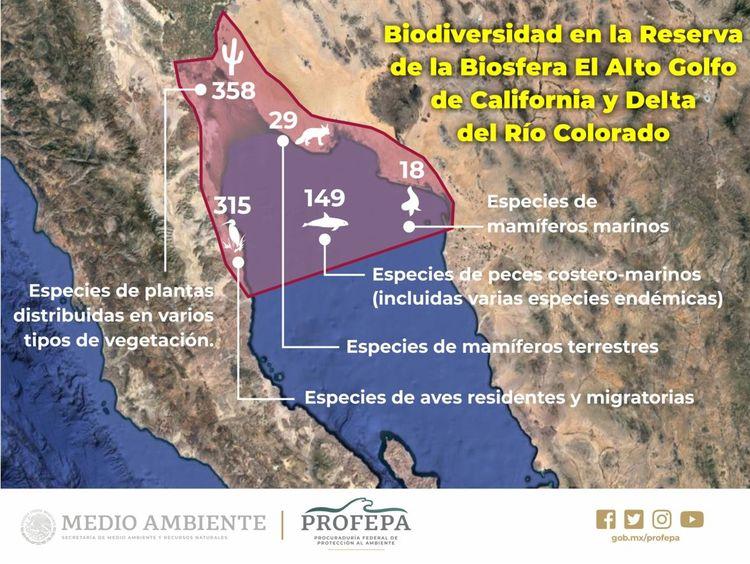

Previously, in 2018, under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (different from the Pelly Amendment), the Upper Gulf fishery was embargoed, located north of the Gulf of California at the apex of the states of Baja California and Sonora, an area declared a Biosphere Reserve because it is the habitat of wild species such as the vaquita marina and the totoaba.

“Under this law (the United States) imposed this punishment (embargo) but it only covers fishery products from the Upper Gulf, which are the species of blue shrimp, brown shrimp, the sierra, the curvina and other fish species,” Oliviera said.

This embargo is still in force, so that fishermen deliver their products to retailers, but it cannot be exported to the United States. Despite this restriction, Mexican fisheries have not had economic effects because they continue to be illegally traded in U.S. territory but now in the hands of those who already had control of routes to trade other species illegally, Sanjurjo said.

“Shrimp that is legal, for example, and can be moved in Mexico, suddenly appears in the United States. There is a dark passage there... because by closing the legal channels for shrimp fishing, you opened others for them... then the only way to sell them is through people who already have the routes, the channels of illegal trade,” said Sanjurjo

It's impossible for the embargo to affect illegal fishermen, Sanjurjo added, since they don't use legal channels. The measure affected fishermen such as those in his organization who are looking to make fishing a sustainable activity, since they use fishing gears that give added value by not harming the vaquita, but their main buyers are in the United States, where there is a larger market looking for these businesses and sustainable consumption.

As long as the U.S. market is closed to fisheries in the Upper Gulf of California, sustainable fishing models will be unfeasible for anglers in the region, he said.

Thus, instead of discouraging illegal fishing, it gives it more species to incorporate into traffic, says Sanjurjo, who added that if what happens in the fisheries of the Upper Gulf extends to national fisheries, “it would be dramatic” for the country.

Marine Vaquita population and ongoing efforts

An observation cruise was sailing in the Upper Gulf from May 18 to 25 with scientists and environmental organizations on board when they saw marine vaquitas, which are estimated to have a 76% probability, corresponding to 10 to 13 specimens, including one or two young, according to the report of the Vaquita 2023 Research Cruise.

It was reported that this calculation is approximately the same as that of October 2021, that the individuals sighted looked healthy and that although there were no vessels using nets in the Zero Tolerance Zone, there were in other areas where vaquitas were sighted.

Regarding the findings, Adán Peña, head of the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas (Conanp), commented at an event organized by Oceana on June 8 that in 2021 they had registered a trend of 8 possible minimum specimens, while “in 2023 we have a trend of 10 to 13 and besides, we have identified young that were born 4 months ago, that means that the species has a chance of survival”.

In this regard, Pesca ABC, which collaborates in the acoustic monitoring of the marine vaquita, through Sanjurjo, noted that this is the first time in 10 years that there have been more acoustic detections (61) of the species than the previous year, in the Zero Tolerance Zone (ZTC) within the Upper Gulf of California Biosphere Reserve and Colorado River Delta.

However, he pointed out that an increase in acoustic detections does not mean an increase in the population and that in any case it is that the population has been maintained and that they are reproducing, due to the sighting of young.

Fishermen from the organization Pesca ABC installing an acoustic receiver to monitor the vaquita marina in the Upper Gulf. Source: Pesca ABC

Regarding the presence of vaquitas in unprotected areas, the report noted, it highlights the need for the expansion of the ZTC and the installation of more concrete blocks to stop gill fishing before the start of the next fishing season in September.

In the cruise ship report, the experts pointed out that “the apparent decrease of more than 90% in the presence of pangas and gillnets within the ZTC, the last stronghold of the vaquita, is probably the most significant step taken to date to save the species.”

In a post on social networks, Conanp indicated that its incumbent will seek the expansion of the Tolerance Zone polygon and will continue in dialogue with the fishermen in the area.

Also recently, the Secretariat of the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) published the Government of Mexico's Compliance Action Plan to prevent illegal fishing and trade of totoaba, its parts and/or derivatives, to protect marine vaquita, which will be reviewed in November at the next meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

However, if this plan does not satisfy other countries, Olivera points out that another trade sanction could be imposed on Mexico, such as the export ban on the list of wildlife species registered in this convention, which had already been imposed on it in March 2023 through notification No. 2023/037 and was withdrawn due to the presentation of the plan.

“It's been almost five years since this administration and we're still struggling and publishing new plans and new promises and we're not there for that. There should be an implementation of all regulations, insurance for the protection of the vaquita and alternatives for anglers. That is why international pressure and that is why the type of sanctions that are coming because here there is no longer a response from the dependencies in Mexico,” he said.

Certifying fishing for export and increasing surveillance

Fishermen in the Port of San Felipe. Source: Pesca ABC

Despite international pressure, Olivera points out that with the dismantling of support for the fishing sector and for inspection and surveillance, it is clear that there are other priorities for the Mexican government.

“There are decisions that are taken without involving the fishing sector or the NGOs and there is a total absence of the authorities. In general, there is a feeling of abandonment towards the fishing sector and therefore a lack of action on the part of the Mexican government with fishermen, with conservation, with agreements, with laws, in general a total neglect of fishing and conservation,” he said.

Under the logic of encouraging illegal fishing, Enrique Sanjurjo suggests that the Mexican government should promote an export standard through which fish and seafood can be certified as complying with regulations and can be exported.

“Bringing all the world's fishermen to legality is impossible, the tendency is to lead them to identify and the few who are doing well and we are going to generate certain incentives to show that they are doing this well. Instead of punishing everyone, it's differentiating a few and starting to migrate so that more and more people join this path of legality, but little by little,” he said.

Comentarios (0)