From the Mapuche worldview, when someone leaves material life, they begin a journey to wallmapu, a territory occupied by this culture that comprises a region of Chile and Argentina in South America. This is where his journey, together with other sister beings from nature, such as the whale and the wolf, is launched to Wenuapu, where his Am, the soul, finally rests.

The destruction or predation of Mapuche territory means disease in people. Cristian Chiguay, lonko (traditional Mapuche authority) from the Yaldad community and also leader of the Wafo-Wapi Association, explains: “A natural space that is poisoned by misuse and bad industrial practices, although it is not death, but it is the disease for the Mapuche people and for their essence, which is the spirituality that our people live by”.

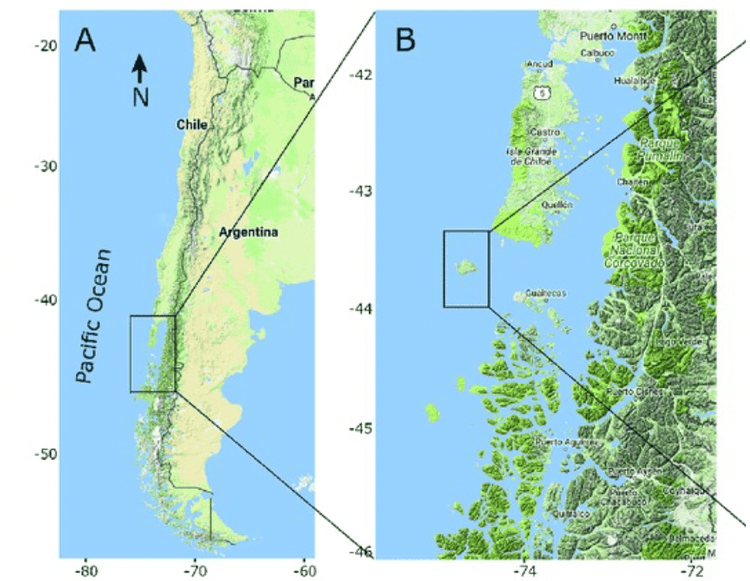

The 213.7 km2 area of Guafo Island in Chile, south of Chiloé Island, is part of this sacred territory for the indigenous Mapuche-Williche communities who point out that the conservation of this space has been their ancient use, and that it is now interrupted by extractive processes, according to a publication published by the organization WWF Chile.

In 2016, in the midst of Mayo Chilote, a crisis caused by the flowering of a harmful alga that seriously affected fishing in the region, the salmon industry dumped more than 4,600 tons of decomposing salmon off the coast of Chiloé Island, generating protests that paralyzed and isolated the Chiloé archipelago.

Chiguay points out that at that time, the malpractices of salmon farming and midiculture were evident, such as the pollution it generates and the lack of control and supervision by the authorities.

In addition, the indiscriminate extraction of wood, a mining concession in the area and attempts to sell it are latent threats that can destroy this space of high biological and symbolic value.

In view of this, 11 indigenous Mapuche-Williche communities have undertaken the process to request the recognition of this area as a Coastal Marine Area for Indigenous Peoples (ECMPO) before the Undersecretary of Fisheries and Aquaculture (Underfishing) to ensure its conservation.

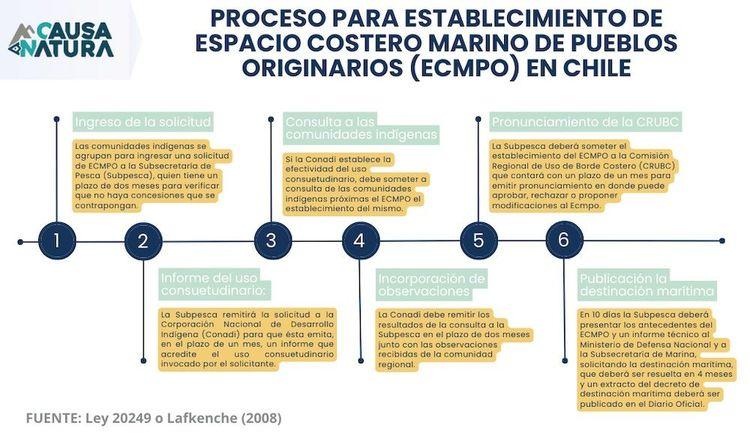

The ECMPO are a conservation model created based on Law No. 20249 or Lafkeenche Act, which places the administration in the hands of an association of indigenous communities that have given it regular use with the intention of maintaining the traditions and the use of natural resources with which they have a historical-cultural connection.

Images of Isla Guafo in the catalog of private islands for sale in 2020, where their value was set at 20 million dollars. Source: Private Island Inc. company website

ECMPOs represent self-government, alliances and sustainability

Unlike Protected Areas, explains Jaqueline Montecinos, coordinator of marine biodiversity and ocean policies at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF Chile), in the ECMPO marine space is granted in perpetuity for administration to native peoples.

According to Chihuay, this makes it a powerful tool that provides the possibility of self-governing spaces and making them sustainable over time.

The space management plan can be shared with external parties or third parties, for example in artisanal fishing and conservation activities. This is where the power of alliances between the various actors who also seek the conservation of the biodiversity and culture of the area is manifested.

Although WWF Chile has accompanied the Wafo-Wapi Association throughout this process, it clarifies that this initiative is led by communities of native peoples and only supports with scientific, technical and political advice or they are responsible for giving greater visibility to the great work they have done.

The requirement of the Lafkenche Act to have an administration plan, an area monitoring plan, is something that gives ECMPO a greater advantage over Protected Natural Areas where “no one requires monitoring, no one requires ensuring that these areas meet their conservation objectives and if they don't comply, no one takes them away from the State,” Montecinos points out.

For the Mapuche people, conservation is not an action, but it is part of their existence, and therefore, once the ECMPO is recognized, Chiguay mentions that activities that are in accordance with their existence and not those that make abusive use of resources, “because we are native peoples whose mandate is to protect biodiversity, as is known in the Western world, and that is our mission”.

A powerful tool with a long wait

One important thing to note is that a characteristic of the ECMPO is that once a request is submitted to the SubPesca, any other request for use that was in process is frozen and a protection measure falls on that area, Montecinos points out.

This quality has made many communities see this tool as a means to protect their territories and has caused that, according to the SubPesca portal, by March 2023, 100 ECMPO requests have been submitted, of which only 13 already have their destination agreement, which is the document that formalizes the delivery of space to the community administration.

And although the Lafkenche Act establishes very specific deadlines in the process for establishing ECMPOs, Yacqueline Montecinos points out that due to the large number of requests, the responsible institutions have not been enough to meet them all and approval times have become longer than stipulated by the Act.

The challenges ahead

Currently, the ECMPO Wafo-Wapi request is waiting to be reviewed by the Regional Commission for Coastal Border Use (CRUBC), that is, in the transition from the fourth to the fifth step of six total to obtain the destination agreement, while the management plan is just beginning to be prepared by the communities and the other actors involved.

There is still no forecast of when it will receive the maritime destination, but once published, the Wafo-Wapi ECMPO will face new challenges, says Yacqueline Montecinos, among those that are most concerned are the budgetary ones to be able to implement monitoring, surveillance and management plans, since once delivered by the State, it has no resources to deliver to the communities.

Meanwhile, the Mapuche community has solved many other challenges that have allowed them to reach these last levels without conflict, thanks to good collaboration and communication, which put into practice the spirit of the Lafkenche Law.

This is just one action in the constant struggle of the Mapuche people against the extractivism of natural resources, where they seek to reorient forms of production, education and promote a vision based on respect for nature.

Comentarios (0)