In mid-May, three armed men came to threaten them. “We don't mess with you and you don't mess with us. And if someone gets in, we'll fix it here,” they told the defenders of the Nueva Morelia ejido, in Chicomuselo, a municipality in the highlands of Chiapas, in southern Mexico.

The warning was that mining, mainly barite, would return. The mine, owned by Canadian company Blackfire Exploration Ltd. has been closed since 2009. At that time, a series of demonstrations, complaints and the murder of the activist Mariano Abarca Roblero led to its closure.

One month after the threats, ejidatarios report that during this time there has been extraction work at the Grecia mine, named after the ejido where it is located, at the top of the Chiapan Mountains.

“People are still climbing (the saw) in vans. The National Guard is already in the town, but when they leave they say they will come back for more material. Hopefully they will no longer return and the government, together with Profepa (Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection) will intervene and put a definitive stop to them,” said one of the land's defenders in an interview, who for security reasons prefers to remain anonymous.

Regarding those responsible, the defender does not know for whom they are extracting the material, but they have previously reported attacks by the mining company, as well as the participation of organized crime in the area.

In Mexico, mines owned by Canadian companies have generated conflicts over the defense of territory in different states of the country. Photo: Margarito Pérez Retana/cuartoscuro.com

This is not the first time that illegal extractions have been reported. In October of last year, local media reported that there were concerns and fears about the reactivation of mining activities in Chicomuselo.

After last month's threats, the ejidos sought out the National Institute for Ecology and Climate Change (INECC). They had their contact because they had recently been in the region to carry out environmental studies.

On May 18, after the meeting, Agustín Ávila Romero, in charge of the Office of the General Directorate of the INECC, sent a letter addressed to the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) in which he requested immediate attention for the community.

It didn't take long for groups and academics who have been accompanying the ejidos to join. Professor Elisa Cruz Rueda, from the School of Management and Indigenous Self-Development of the Autonomous University of Chiapas, was one of those who was able to contact the CNDH and connect with defenders due to the distance and the risk of going to the Commission to ratify the complaint

“What the colleagues in the area reported to us is that days later (after the threats) there was more police presence. The State's preventive measure arrived to confirm that the environmental defenders were doing well,” the professor explained.

However, there has yet to be another response from the authorities.

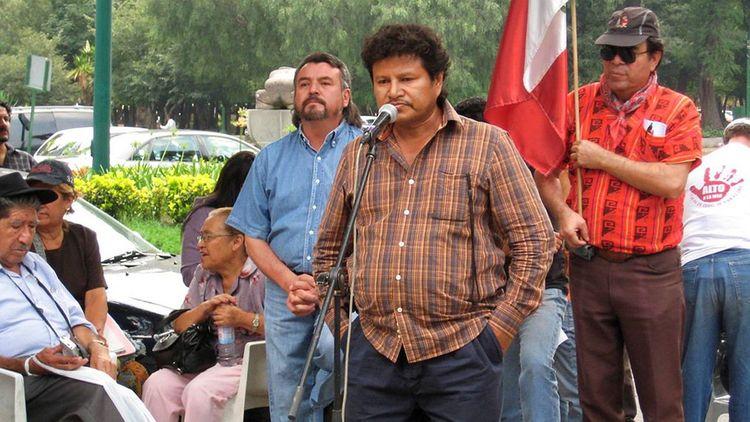

Protest against mining companies. Photo: Margarito Pérez Retana/cuartoscuro.com

Report a country

The Greece mine conflict is not new. It has a history dating back to 1999 when the national company “El Caracol” applied for a concession to exploit barite, one of the most sought-after minerals in the oil industry.

In 2006, the concession was transferred to Blackfire. Although initially welcomed by the Grecia ejido, residents of other low-lying areas of the mountains soon reported contamination. Rivers, which are the main resource for making use of water, began to be colored by the use of cyanide and arsenic in washing minerals.

In addition to the effects on the environment, in Nueva Morelia they remember that social dynamics also changed. Bars and brothels were set up, despite being banned in the ejidos. Drug use also spread.

The situation appeared until the assassination of Mariano Abarca, one of the most active opponents and community leaders, in November 2009. The case escalated to international media, so the government had to shut down the mine.

“It was reported to the Ministry of the Environment and to Profepa that the mining company was violating its own concession stating that it would not cause harm to the environment. The activity stopped because there was a very important process of resistance in the area, but the concessions were not canceled,” said Professor Cruz Rueda.

Faced with the closure, it was announced that the company Blackfire was detected suing the Mexican government for almost 800 million dollars. They argued that the closure violated different legal provisions such as those of the then North American Free Trade Agreement and that the money would be used to recover what was invested in the mine.

However, after statements in 2010 (retrieved by the organization Mining Watch Canada) in which Blackfire admitted that it had been mining in the community of Nueva Morelia due to a mapping error and said that it never threatened to sue the Mexican government, there is no more information about the company.

In 2019, legal action came, but from the family of Mariano Abarca, who filed a complaint with the Federal Court of Canada against the Canadian government for omission in the mining conflict. However, after years of waiting, the Court rejected the appeal and denied an investigation.

The process has not ended, on June 8, it was reported that, in the face of the refusal, the complaint of family members had been brought before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

Mariano Abarca, community leader and land defender, assassinated in 2009.

What is pending

Although as of the closing date of this note, there has been no other encounter with armed men, defenders say that there is fear in the community.

“I think they're waging psychological warfare. The community is nervous and afraid. Many of the people have gone to sleep in the mountains, taking children, the elderly and women. It is a terror, because although the situation is calmer, they are still there and when they remove the material they are contaminating the water that supplies our ejido,” said the land defender.

In addition, insist that it is necessary for Profepa to show up for an inspection and for the federal government to take action.

“What we want is for this to reach the authorities and, as a saying goes, 'the more we play, the more we play the louder and more often. ' So we must not stop knocking on doors for justice to be done because what we want is to live without fear,” he concluded.

Comentarios (0)