Some start the van, others cooperate for gasoline, some more sign up to do the job of tracking pests or reforestation; when the day is over, the elderly offer food. Trying to save La Malinche from a plague that destroys thousands of trees a year has been a titanic task for communities settled at the foot of the mountain, in the state of Tlaxcala.

It is the well-known 'bark worm' (Dendroctonus mexicanus Hopkins), identified for the first time in the community of San Pedro Tlalcuapan, with an identified involvement of one hectare.

This pest is considered to be one of Mexico's main phytosanitary problems. The larvae settle under the bark of weak or diseased trees and later transform into beetles, which feed on plant tissue. In a matter of months, the infected tree dries up and dies.

Photo: Mario Jasso/ Cuartoscuro

“These are very dangerous insects because of the damage they cause. They can affect anything from a small group of trees to hundreds or thousands of hectares,” notes the National Forestry Commission (Conafor) in its Forest Health Manual.

“These are very dangerous insects because of the damage they cause. They can affect anything from a small group of trees to hundreds or thousands of hectares,” notes the National Forestry Commission (Conafor) in its Forest Health Manual.

Stopping the plague is not an easy task, as it spreads quickly. In 2019, it went from affecting one hectare to being irrigated elsewhere in the forest.

Uriel Flores, one of the young leaders of the community of San Pedro Muñoztla, explained that the first few months were uncertain.

La Malinche or Matlalcuéyatl, the fifth highest mountain in Mexico, has been a protected natural area since 1938, with the category of National Park, so the extraction and sale of wood is not allowed.

“Since trees are not cut down in communities, there was very little information, and a lot of doubts began to arise. How to resolve this? How to attack this pest? , we didn't know anything,” Flores said.

The sanitation of bark chipping insect pests involves a radical measure: throwing away infected trees, as indicated in the Conafor Forest Health Manual. The action, in turn, requires authorizations from the agency, in accordance with article 113 of the General Law on Sustainable Forest Development.

Having permission to carry out the only possible phytosanitary measure forced communities to face their own legal loopholes: legal land tenure.

“While that was happening, the plague continued to advance,” Uriel said.

In affected communities, which are mostly governed by systems of uses and customs, there are no legal deeds, only evidence of ownership.

This situation, in addition to a series of decisions by state and federal authorities in which residents were not considered, encouraged communities to work in an articulated manner.

The plague does not stop

It is difficult to calculate how many hectares of forest have been impacted by the plague of bark cutters in the La Malinche forest, whose total extension covers 46,112 hectares in 12 municipalities of Tlaxcala and Puebla.

The statistics depend on the residents, as they identify the affected areas and then report to Conafor.

According to the Conafor Forest Pest Sanitation Notification Report, a total of 1,772 hectares were affected by pests in Tlaxcala by 2021. The figure coincides with the estimated impact on the part of organized communities.

In the community of Muñoztla, members of the Forest Surveillance Committee have witnessed their progress. They went from one hectare to more than 70 in three years, despite combat efforts.

Among the most representative vegetation of the protected reserve are the oyamel and ocote trees (those most affected by the plague). It is the habitat of more than 900 species, dozens of them endemic, such as the canelo chupaflor, the Mexican buzzer, the red horse, the Mexican thrush, the mule bat, wall jumper, blue juniper, white-backed swiftlet and blackbird, among others, according to data from Conanp.

This pest, also known as the 'Mexican bark cutter', has been identified from northern Mexico to Honduras, as indicated in a report from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

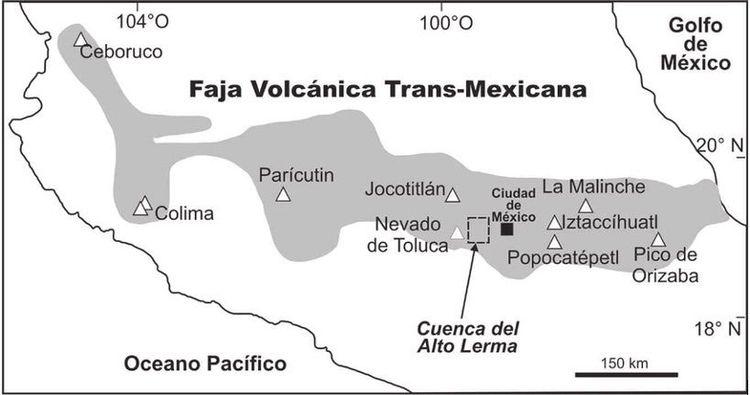

The area with the greatest distribution is central Mexico, along the Transverse Volcanic Belt (FTV), which ranges from the central area of the Pacific, at the height of Jalisco and Colima, to the center of the Gulf of Mexico through Veracruz.

Graphic: Shigeru Kabata/Researcher at the University of the Americas Puebla (UDLAP).

The UNDP document, signed by researcher Diego Reygadadas Prado, points out that this bark beetle takes between 42 and 124 days to develop in a tree, from its larval stage to becoming a beetle.

This is not the first time that the forests of Tlaxcala have been besieged by forest pests. The Conafor historical pest record shows that between 1990 and 2020 about 5,299 hectares were hit by bark cutters, mainly in 1990, 1991 and 2013.

The most common pest in the state is the growth of mistletoe, a semi-parasitic plant, which attaches to the branches of the tree, extracting its sap and sugars, with a total of 14,442 hectares affected. However, it is, to a certain extent, less harmful, since it can be cleaned manually, without having to cut down the trees.

The dispute over wood

One of the most sensitive points between the relationship between communities and government to end the plague is the use of wood, once the trees are felled.

Between 2020 and 2021, the Covid-19 pandemic intensified the economic crisis in communities, so that the sale of wood represented, in principle, an opportunity to deal with the situation, explained Socorro García, president of the Malintzi/ Matlalcueye Network: Dialogues for the Mountain.

The government of Tlaxcala provided residents with a list of companies that would buy the wood, to “help communities”.

They started paying 70 pesos per cubic meter of wood, then, in the face of community dissatisfaction, 250 pesos, García said. The lack of experience in forestry took its toll, because over the months they realized that the payment was well below the commercial value, said the community leader.

Based on the Conafor Timber Forest Products Price System, the price of large wood, as of the first half of 2021, exceeded 1,400 pesos nationwide per cubic meter of untopped logs placed to be loaded onto the truck.

“Where was all that money? Well, in the squares between the state government and the loggers. It wasn't very difficult to guess that a business was there, if they came for the wood from states like Hidalgo or Oaxaca,” he questioned.

Currently, they have managed to market the product at prices ranging from one thousand to one thousand 200 pesos.

Photo: Mario Jasso/ Cuartoscuro

Another subsequent problem was the illegal felling of healthy trees, in areas close to where permits were obtained to cut down infected trees, Socorro García said.

Right to participation

García explained that the Malintzi/ Matlalcueye United Community Network, made up of villagers, activists and academics, has been a fundamental axis for social participation in the environmental defense of La Matlalcueye (goddess of water).

This Network was integrated in 2020 to contribute to the intercommunity organization of the United Communities in Defense of Matlalcueyetl, formed in turn by the Community Committees.

“In the beginning, the agencies (of the government) began to make very technical decisions, the Committees were not being listened to,” said President Socorro García. Among the issues that generated dissatisfaction was the issuance of notifications in the name of the head of the State Ecology Coordination and not of the owners, the choice without consultation of the company that would carry out the sanitation and the use of agrochemicals.

Together, the Network and the Artemali collective of women artisans from Puebla insisted on the right of peoples to participation, through forums and meetings.

“We needed to put into practice the application of our rights as indigenous communities, original communities. We spoke about the right to self-determination, to decision-making through Assemblies, to the validity of Committees,” he said.

The conflicts with the government of Tlaxcala over the payment of wood and the spread of the plague led residents to demonstrate in Mexico City in May 2021, to call on the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat) to resolve the situation from the perspective of indigenous law, recognizing the possession of land through ejido records.

The Community Committees of each location operate independently, but are in communication to share knowledge and experiences.

One of the tasks of the San Pedro Muñoztla Forest Surveillance Committee is to monitor the pest, which consists of going deep into the mountains to locate infected trees and write them down in a log. They have also learned to use geolocation tools to facilitate tracking, said Mayra Galicia, who is also part of the group.

“It is identified if there are pests present, the diameters of the tree are measured, its physical conditions, if it has a green leaf, a brown leaf or no longer has leaves. From that, a phytosanitary report is made and delivered to Conafor offices to authorize sanitation,” he said.

A food engineer by profession, Galicia has been key to the development of technical skills. Others, such as Uriel Flores, do the same with the tasks of education and awareness-raising through art.

In addition, those involved do other work to safeguard the forest, such as reforestation and breaches to prevent the spread of fires.

Both Flores and Galicia agreed that it has been a process with ups and downs, with moments of stress and discouragement, due to organizational differences and apathy on the part of the authorities.

But there is also learning. Mayra said that everyone, in one way or another, is putting in their efforts to build collectively. “Even older women who can't climb the mountain tell us 'when they come down here I'll have their breakfast', and that's their way of contributing,” she said.

For Uriel Flores, this has represented an opportunity not only to get involved with the mountains, but also to reinforce a sense of belonging.

“The experiences of getting to know the town, meeting more people and knowing the thinking of many people, dealing with everything. It has been a learning experience. We used to say that we were saving the mountain, but in the end I think the mountain is saving us,” said Flores.

Comentarios (0)