With little faith that they will resist the crisis in the sector, deep-sea and coastal fishermen have been making the last effort to navigate the great challenges for more than 40 years, as the oil industry in the Campeche Sonda coexist with the environmental regulations of living in a Laguna de Términos Flora and Fauna Protection Area (APFF).

Isla del Carmen, which was once one of the main fishing ports in Mexico, thanks to the capture of pink shrimp and seven beards, is now starkly contemplating the progressive decline of its fishing fleet with the overexploitation of species such as shrimp, octopus, horse mackerel and snails. In addition, its disappearance hangs in the balance due to the ecological impact generated by Petrleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

The men who were born with fishing under their arms and perfected the profession with centuries of tradition, including the members of the Carmen Federation of Deepwater Fishing Cooperative Societies, were threatened overnight to give up deep-sea fishing; at that time they recognized that the confluence of the exploitation of both riches was already impossible.

Faced with the restriction in fishing areas around marine platforms and the failure to meet the government's commitment to reopen fishing areas, they slowly migrated to aquaculture. Although the activity was boosted 20 years ago in the region, they still don't think it's profitable at all, but for now it's their only economic alternative.

To start as rural producers in aquaculture, great leaders such as Adolfo Hernández Maldonado, president of the Carmen Federation of Offshore Fishing Cooperative Societies, began to move, who says that with the support provided by the Pemex Community and Environmental Support Program (PACMA), they purchased land in the Atasta Peninsula and in Sabancuy to manage rural aquaculture farms.

“It was until 2008 when we started producing, since it took five years to obtain the Environmental Impact Manifestation (MIA) in addition to other requirements contemplated in the General Law on Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture,” he says.

He adds that by 2008, academics from the Juárez Autonomous University of Tabasco trained them to operate 10 tilapia aquaculture projects, seven of them in the “Jobal” ejido, of the Sabancuy Municipal Council, and another three belong to the Atasta Peninsula.

Offshore fishermen report that being employed in aquaculture has been complicated, since financial and infrastructure difficulties are seen in the shortage of offspring, the high price of food; in addition, it is more difficult without constant technical advice to improve the technological processes of cultivation.

Despite this, producers have put all their efforts into practice to set off the activity; in addition, they have adapted to all the conditions for learning to use it in circular geomembrane ponds, where they protect the species to achieve quality production and therefore increase commercialization.

Tilapia aquaculture projects with circular geomembrane ponds, in the “Jobal” ejido, of the Municipal Council of Sabancuy, Carmen. (Photo: Adolfo Maldonado)

Obstacles to fishing and aquaculture

In the opinion of researchers working on the “Fisheries and Petroleum” study of the Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Ecosur), Eva Coronado Castro and Alejandro Espinoza Tenorio, highlight that projects such as aquaculture are sometimes interrupted because they do not have comprehensive long-term planning.

They cited that some of the problems affecting the effectiveness of programs are poor planning; among them, land tenure and use, as the main input for carrying out aquaculture. On the other hand, power supply failures limit performance to operate specialized machines, since they simply do not specify the processes because they do not have energy.

Regarding production, they indicated that we only talk about good management practices and how to offer a quality resource, but training is essential in terms of administration and marketing of the product.

“In small communities such as the Atasta Peninsula, where aquaculture has been implemented, the biological part has worked, the problem is that many of the materials have been subsidized to generate the activity and there is no real commercial plan. For example, there is training, equipment and funding for the first harvest; then, what they sell is their only income, because they are not capitalized to make a second harvest, all of this prevents maintaining stability in the project,” says the researcher from the Department of Sustainability Sciences at Ecosur.

Uncertainty in the sector

Factors such as the lack of control of fishing in the Campeche Sonda, in addition to environmental deterioration that alters the reproduction and survival of organisms, have caused a decrease in catch volumes compared to other decades, which poses a great risk to fishing communities, as indicated by Dr. Eva Coronado Castro, also a professor at the National School of Higher Studies, Unidad Mérida, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

Fishermen return from the Campeche Sonda to arrive at the docks with shipments of fish and seafood. Photo: Lisseth Castro

He adds that the impact on marine fauna is serious due to the overexploitation of species such as shrimp, which are increasingly decreasing in size because they are in younger populations and do not reach their maximum reproduction.”

Shark populations are also very affected and there is little control over what is extracted, which is why it has been included in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

For his part, Dr. Alejandro Espinoza Tenorio argues that the scenario is very complicated for fishermen, in particular for young people and women as the most vulnerable and invisible in this area; however, the contribution of each of them means a pillar that supports fishermen, due to all the support they provide behind the crude stage.

Fishermen return from the Campeche Sonda to arrive at the docks with shipments of fish and seafood. Photo: Lisseth Castro

“With the decline in fishing resources, combined with insecurity, climate change and the indirect effects on young people and women, then the degree of uncertainty for the sector is very high,” she emphasizes.

Riverside residents in crisis

Due to legal obstacles and lack of support from Pemex, coastal fishermen live together in a more drastic scenario; they have not yet applied aquaculture as a palliative, because they are currently bankrupt. The devastation is not only reflected in the scarce catch, it is also evidenced by the “Arroyo Grande Fishing Refuge” with the deterioration of the 12 springs eaten by salt water, which notice a collapse every time workers walk among them with loads of fish, mollusks and crustaceans.

Riverside fishermen cleaning shrimp in the “Arroyo Grande Fishing Refuge”. Photo: Lisseth Castro

Riverside fishermen cleaning shrimp in the “Arroyo Grande Fishing Refuge”. (Photo: Lisseth Castro)

This area forms part of the southwestern tip of Isla del Carmen, which connects to the coast of the “Laguna de Términos”, where floating debris accumulates that increase pollution in mangroves; the smell it gives off urgently calls for a call to rescue this Protected Natural Area, which is an important breeding ground for various species.

In front of the pier, there are 20 wineries dedicated to the sale of marine products, where you can see the ruin that responds to the sadness of fishermen such as José Iván Piña Galán, leader of the La Manigua Fishermen's Cooperative, who explains behind the warehouse that in addition to the impact generated by Pemex, they face natural phenomena that make catching more complex.

“All this year there was no good production, with the arrival of Cold Fronts and tropical storms, the impact intensified; we no longer recovered the investment we made, we are in a big crisis, we give it a maximum of five years for fishing to disappear,” he shares.

Concerned, but aware, the leader considers it essential to have an alternative program such as the cultivation of species to generate income during the closed period and low catches, which would allow them to support their families in the face of poverty.

With great certainty, he states that, “the farm could be created on the Atasta Peninsula that connects to the Laguna de Términos, but it is difficult to obtain the MIA, which costs more than 100,000 pesos. I think that growing shrimp and tilapia on farms would allow us to resist.”

Discrepancy

With his eyes depressed, but focused on the sea, the president of the Federation of Coastal Fishermen of Ciudad del Carmen, Vicencio Luna Pérez, believes that aquaculture will not face the fishing crisis, due to strict compliance with ecological regulations at all scales.

The representative of 12 cooperatives recalls with disappointment that, for a decade ago, he managed a pilot project for the breeding and fattening of smedregal in cages; at that time he took training, but in the end the plan was disapproved, supposedly due to lack of documentation.

“The price of food and the collection of electricity are very expensive here; in addition, the economic recovery of investment is slow; the amount of production must be high to market and sometimes it's impossible, because in the process of moving fish die, in the end you have more losses and expenses, it's definitely not ideal,” he says.

He highlights that, together with his colleagues from the cooperatives of Atasta, Isla Aguada, Sabancuy and Ciudad del Carmen, they will continue to demand the established agreements in which they are beneficiaries. Well, in recent years, the social programs of the federal and state governments have been delayed without warning and this has led to fishermen protesting at the State Government Palace; on other occasions, under the intense sun, they have courageously challenged the authorities with blockades on the access to the El Zacatal Bridge.

Fishermen from the cooperatives of Atasta, Isla Aguada, Sabancuy and Ciudad del Carmen. Photo: Lisseth Castro

Fearing that the collapse of the sector will come, Luna Pérez sighs, “We can no longer endure the closed period and the gradual increase of the exclusion zone, there is no alternative but to recover traditional fishing with programs to compensate for the damage.”

Fishing community disappears

Surrounded by veterans who know the art of fishing from start to finish, Adolfo Hernández Maldonado, president of the Carmen Federation of High Altitude Fishing Cooperative Societies, waits sitting with his cup of coffee in the restaurant that in the past functioned as the Regis Cinema.

At the time, he narrates with grief the crisis in which they were forced to give up fishing, exhausted from hearing the promises to recover their main economic activity, resigned they decided to opt for aquaculture projects to survive.

“With the discovery of the site called Cantarell Complex, in honor of our colleague Rudesindo Cantarell Jiménez, Pemex arrived in this region in the late 1970s, by then there were more than 470 vessels dedicated to capturing shrimp, which represented a source of employment for more than 30,000 people; 10 freezers and eight shipyards also disappeared.”

He adds that today there are only three ships that still sail to Tamaulipas from that fishing fleet: “Carey”, “Gilda III” and “Alonso Felipe de Andrade”, the latter being decorated every year in the month of July to take the traditional sea walk on the island, where thousands of fishermen gather to worship the image of the Virgin of Carmen.

The other boats were sold to fishermen from other regions and about eight were reduced to scrap submerged in the sea, which stand out from the modern Pemex boats that are anchored at the pier of the “Alonso Felipe de Andrade” Municipal Market, used for boarding passengers to the Magical Town of Palizada.

After being abandoned at the pier of the “Alonso Felipe de Andrade” Municipal Market, tall boats turned into scrap metal. (Photo: Lisseth Castro)

Hopeless

The representative also reports that the golden age was dying with Pemex when the highest percentage of shrimp was exported to the United States; because in 1994 the federal government delimited prevention and exclusion areas to 600 square kilometers to approach Cayo Arcas, Ixtoc-A, and Dos Bocas, due to the location of ships and the Ixtoc-A, Akal-C, Ku-H and Pol-A platforms.

“All this problem worsened after the terrorist acts of September 11, 2001 in New York, because with the justification of preventing and eradicating any similar behavior, increased surveillance was required at important facilities in Mexico, such as oil platforms. With this, the restriction increased to 1,205 square kilometers in the Campeche Sonda,” he says.

This agreement was published on September 11, 2003 in the Official Gazette of the Federation between the Secretariats of the Navy (Semar), Communications and Transportation (SCT) and Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (Sagarpa).

He explains that during the administration of former President Enrique Peña Nieto, the federal government promised to release 15,000 square kilometers of the restricted area, but that never happened.

“For the exploration, they brought a Fishing and Oceanography Research Vessel (BIPO), from the National Fisheries Institute (Inapesca), but they never gave us results, we were totally disappointed because they only gave us a long one,” he says.

After that disenchantment, they chose to travel to Tampico, Veracruz and Tamaulipas to fish and resist the economic streak they were suffering, but they did not succeed. In addition, with the increase in the closed period and the limited production - as it was in competition with fishermen from other ports - the fleet gradually began to disappear.

Sources close to Pemex argue that “cooperatives have been “compensated” with the PACMA, which was implemented in the municipalities where Pemex, Exploration and Production (PEP) operates, providing them with in-kind resources such as fishing gear and safety kits.”

They specify that “as part of the oil company's social responsibility actions, its objective has been to support the fishing community to continue their work”.

This million-dollar trick was disguised as a social program to supposedly “compensate for the damage”, although the fishermen insist that the damage is irreversible, as they say that it was a matter of time to lose their “heritage”, since their well-being and quality of life were threatened for more than a decade.

Scenario in numbers

A look at the adverse environment faced by fisheries at the local level is possible through the limited statistical information that exists in the Fisheries and Aquaculture Yearbooks of the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca).

In 10 years, the state's fishing population fell by 28.4%, since in 2010 there were 15,284 people engaged in this economic activity throughout Campeche, but by 2020 there were only 10,932 fishermen.

In the same period, 59% of the offshore fleet disappeared, from 258 active larger vessels to 105. The situation has also been drastic for riverbanks, from 5,362 active vessels in 2010 to only 3,401 in 2020; in other words, in a decade 36.5% of the boats dedicated to artisanal capture disappeared, and with it the livelihood of thousands of people.

The collapse of the fishery in Campeche has impacted its volume of participation in domestic production, which represented 3.37% of the entire country in 2010, with an estimated liveweight catch of 54,533 tons; by 2020 the state's contribution was 2.61% of national fish production, with 50,830 tons of live weight.

This dynamic has represented a change in the species caught in the state. Until a decade ago shrimp were still the main source of income for fishermen, with 8,155 tons caught in 2010, representing 28.7% of that year's state production, followed by horse mackerel (24.4%), octopus (20%), snails (15.6%) and sea bass (11%).

Currently, crustaceans are no longer among the main species, and by 2020 the largest catch volume was octopus (18.6%), horse mackerel (15%), snails (10%) and tilapia (7.4%). Only 2,713 tons of shrimp were caught that year, marking a steady decline in the shrimp industry focused primarily on Isla del Carmen.

Aquaculture is positioned as an alternative, because contrary to the disappearance of deep-sea and riverine fleets, it has increased in 10 years in the entity, tripling in a decade, from 44 aquaculture production units in 2010, to 163 units in 2020.

Environmental effects

Ángel Castillo Novelo, president of the Federation of Deepwater Fishermen of Campeche, represents eight cooperatives that make up 467 fishermen, to whom today he gives a voice through this medium to point out that he does not find the alternative of aquaculture viable to face the fishing crisis.

With a broken voice, he recognizes that the community resists geographical, climatic, social and economic conditions, since it is not only part of food security in the entity, it has also been part of the country's food security.

“The oil company has caused ecological imbalance by invading the sea with tons of garbage and scrap from ships, this waste has caused the networks to break and waste time and production in our work, there are days when I only take out a kilo of shrimp, this reality is no longer possible,” he shares.

Castillo Novelo calls on Pemex to stop fishing, and he also points out that marine pollution exploded with the oil company, causing the migration and death of animals; he describes that larger spills such as Ixtoc I and the collision of the Usumacinta and Kab-101 marine platforms affected part of the ANP mangroves of the “Laguna de Términos” and areas in the “Los Petenes” biosphere reserve.

“I can say with accuracy that from Triangle Island to Cayo Arcas it is the area where we removed shrimp and dead fish from the sea, characteristic of the Gulf of Mexico, including mackerel or verdel, the Isabelita medioluto, a large catfish, in that space the species ran out and no one has imported it, we have even found dead turtles”, he emphasizes.

Imbalance

According to Pablo Ramírez, an Energy and Climate Change specialist at Greenpeace, for a long time the Pemex infrastructure installed in the Campeche Sonda has operated without adequate maintenance, which has caused frequent spills and leaks that directly impact marine fauna.

At least, the Gulf of Mexico coast region has many species classified as endangered; among those that could be affected by the incidents that have occurred, 20 species of cetaceans, sea turtles, more than 1,500 types of fish stand out: 14 bones, 26 sharks and four manta rays, details Pablo Ramírez.

Greenpeace states that the oil company has not allowed public access to ecosystem impact assessments; in response, the organization calls on Pemex to make incident records transparent to analyze the magnitude of the problem in the marine environment, where there is a great loss of biodiversity for a sector as important as fishing.

“The cases we know of incidents are through fishermen who report oil spills or through communities that live off tourism on the coast,” says the environmentalist.

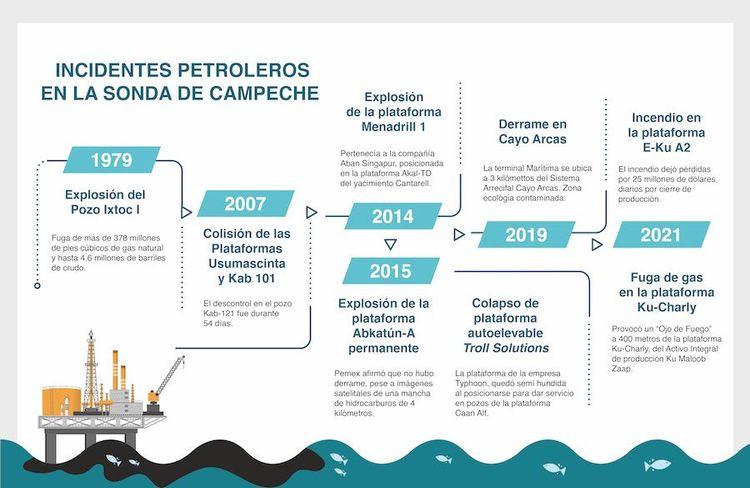

He added that these problems are accompanied by climate change, which has a more stark impact on the most vulnerable communities, where social inequity in the country stands out more. Some of the most shocking incidents are contemplated below:

Challenges

The vast majority of Pemex platforms and other companies operating in the Campeche Sonde are located in the same place where natural fumes and hydrocarbon spills occur.

To determine the impact of each of them, the Gulf of Mexico Research Consortium (CIGom), in coordination with the project “The challenging coexistence of marine ecosystems with the hydrocarbon industry”, led by Ecosur Campeche, are working to establish the monitoring system for hydrocarbon spills in the Gulf of Mexico.

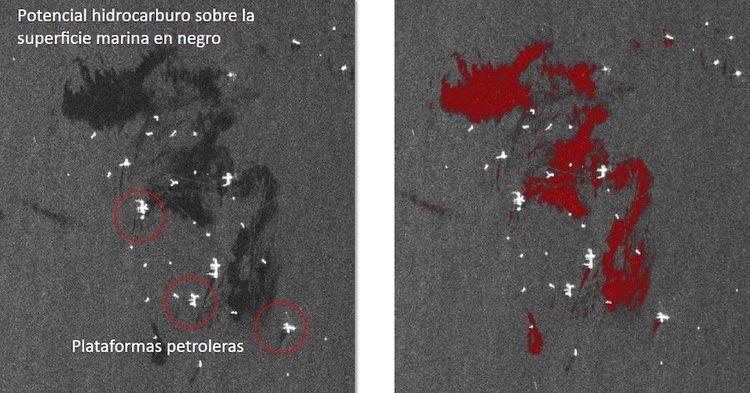

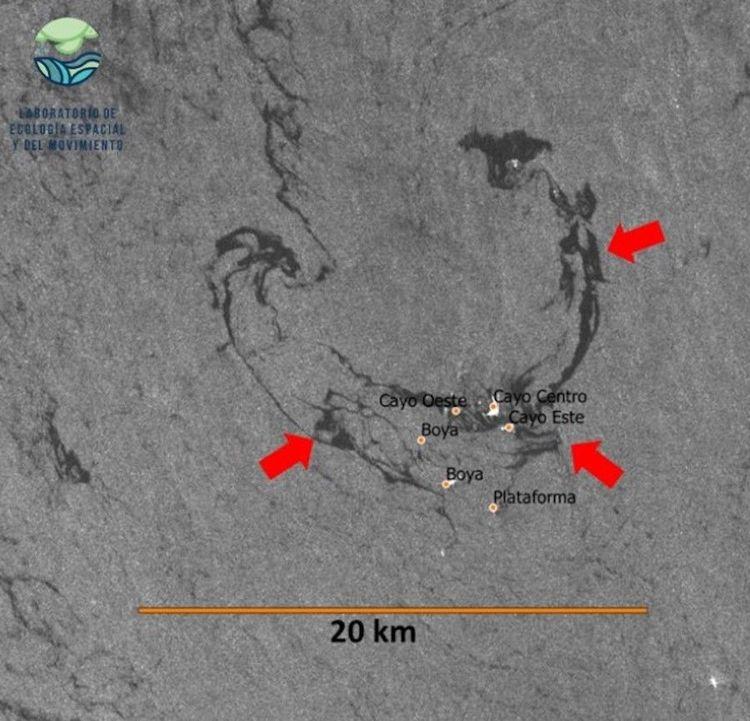

As part of the CIGom team of scientists, Dr. Abigail Uribe Martínez explains that through satellite images, they carry out geospatial analyses of the distribution of biodiversity, as well as of the oil infrastructure in which they detect the presence of hydrocarbons on the marine surface.

“Sometimes it is difficult to detect the spills that we observe through satellite images in the Laboratory of Space and Movement Ecology; but other scientists carry out modeling to know their location and determine the level of damage in coral areas or beaches, in addition to what actions were taken in this regard to mitigate the impact,” he says.

“The amount of oil that emerges from incidents in the Gulf of Mexico varies in quantity, even if they are small, they could be more dangerous because they are recurrent. We studied from 2018 to 2021 where there were an order of 20 to 30 incidents each year, for now we are reviewing the results for 2022,” he says.

Satellite image of synthetic aperture radar (entinel 1, https://scihub.copernicus.eu/) with the presence of hydrocarbons (potentially crude, in black on the left and in red on the right). June 19, 2021, Campeche Sonda.

Radar satellite image of the Sentinel 1 sensor, obtained on October 7, 2019 over the Cayo Arcas reef system area. The arrows indicate the presence of hydrocarbons detected with this technique.

Presence of hydrocarbons detected with Sentinel 2 satellite image (https://scihub.copernicus.es/) obtained on September 24, 2022 on the Campeche Probe. The image distinguishes the oil platforms that are the source of smoke plumes, as well as several black and colored spots that indicate the presence of oil on the surface.

Pemex hides incidents

The expert says that, on several occasions, Pemex does not report incidents, its response is always the same, “they are not spills, but natural emanations”. In this regard, it is urgent that the oil industry assume the responsibility of communicating it to the Secretariat of the Navy (Semar) and to the Security, Energy and Environment Agency (ASEA), an organ of the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat), which is responsible for regulating and supervising the facilities and activities of the hydrocarbon sector in industrial, operational safety and environmental protection.

He adds that companies operating in the Campeche Sonda must follow very strict protocols and courses of action to give continuity to incidents; but since ASEA fines are millions of dollars, the facts are hidden.

“Marine exploitation is very invisible, because if you don't see them on the beach you think they don't exist, but fishermen recognize this and report to us all the time that there are spills. Unfortunately, there is often oil in the huachinango habitat, sharks and sea turtles, and they don't seem to be the so-called water showers,” he warns.

He shares that to know the route of some species, they carry out monitoring, in which they follow the turtles through a satellite chip in their shell, and dolphins and sharks have a little ring inserted into their fin, which connects a system similar to the Global Positioning System (GPS) to locate the animals, so that in the event of incidents they achieve spatial inferences.

The problem for ecosystems will not end, Pemex will open more areas to exploit, as several deposits are in their last reserves. Too much was explored in the wells where they released air pumps to see the contents of the soils, this is very impactful on species, in particular on mammals.

“We want to make visible that, for a long time due to lack of resources and technology, Pemex was the only one who knew the condition of the dumps, because we never knew where they were going, nor did we know if there were environmental compensations. The ideal would be to explore and exploit the sea in a clean way, it's very difficult for the oil industry, but it can be controlled,” he says.

He points out that they are not against Pemex's activities, because they are indispensable for the Mexican economy; but it is also true that there are other practices to predict incidents and repair the damage they cause.

* This work was supported by the Marine Journalism Network (Repemar), promoted by Causa Natura with the help of the Earth Journalism Network of Internews.

Comentarios (0)