Foam at the Juanacatlán Falls in Jalisco is not normal. It is a reminder that pollution is present in the bodies of water that flow with the Santiago River and also the reason why Raúl Muñoz Delgadillo, president of the Citizens Committee for Environmental Defense of El Salto, has not stopped fighting.

Before reaching the waterfall, the Santiago River is fed by the “El Ahogado” stream, born in the discharge of the El Ahogado Dam and travels 9.1 kilometers to reach the river.

The stream has been shaped as a drain for industrial and municipal water discharges from the El Ahogado basin. A “cocktail” of pollution, as Muñoz describes it, that has passed a high cost to neighboring inhabitants and to the environment.

Video by Raúl Muñoz, leader of the Citizens Committee for Environmental Defense of El Salto.

“When we reach the height of the waterfall known as the Juanacatlán Falls, we see that when water falls on the rocks, enormous foam balls form and that is the most depressing spectacle we can see and it is one of the ways in which we can verify that nothing is being done,” Muñoz said.

“On the edge of the waterfall, already at the bottom we have houses a few meters from the riverbed and already (located) in the area where the waterfall has already burst. (The water) has a layer that could be about a meter and a half thick of pure foam that looks like it has snow, and there are multi-family buildings on the edge of the waterfall,” he added.

El Salto de Juanacatlán waterfalls. Photo: El Salto Citizens Committee for Environmental Defense.

A 2011 study by the Mexican Institute of Water Technology (IMTA) found 1,90 chemical substances in the Santiago River. The “Water Quality Study of the Santiago River (from its source in Lake Chapala to the Santa Rosa dam), third stage” analyzed 26 industrial discharges in three sampling campaigns between 2009 and 2010 and concluded: “Industrial discharges were more polluting than municipal discharges, since 87 to 94% of industries do not meet at least one of the parameters of NOM-001-Semarnat-1996”.

More than a decade later, visible pollution in the waterfalls occurs despite Governor Enrique Alfaro's investment of 4.6 billion pesos to recover the Santiago River, Múñoz accuses.

The Santiago River is a sample of what is happening in a country where 70% of rivers are contaminated, as confirmed by the head of the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat), Alicia Bárcena.

President Claudia Sheinbaum has included in her government promises the rescue of some of the main rivers: Lerma-Santiago, Tula and Atoyac; but experts invite attention to the origin of the pollution that is concentrated in the industry, which would prevent toxic substances from harming ecosystems and people in the first place.

Wastewater discharges are an important part of pollution. They are classified as municipal and non-municipal. The latter include the industry whose water can be self-supplied from rivers that then serve as discharge sites.

A review by Causa Natura Media of the titles of waste discharges from the Public Water Rights Registry (Repda) shows that the industrial sector leads the amount of wastewater discharged in Mexico.

If the approved volumes are added to the securities from 1993 to August 2024, the result is that the authorities have given the green light to the industrial discharge of 44 million 389 thousand 297 cubic meters per day. It is worth saying that not all of these permissions operate simultaneously. With validity between 5 and 30 years, the Repda does not specify which ones have already expired.

The effects of wastewater on rivers are multiple, said Omar Arellano Aguilar, professor at the National School of Earth Sciences of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). One is the alteration of osmoregulation, the ability of organisms to balance salt and water.

“Many of the industrial processes take up a lot of salt, a freshwater river should not be flooded... it affects through osmoregulatory changes many organisms that are the basis of the ecosystem, nitrifying bacteria, single-celled species, plants, plankton, zooplankton, all of this is the basis that allows a river to be alive,” Arellano explained.

In addition, the mixture of wastewater discharges alters the balance of bacteria and the oxygen levels that these streams must have, he added.

“Tons of heavy metals, agrochemicals, hydrocarbons, and currently plastics and microplastics have been discharged, which are also already a big problem. So we haven't been able to stop the historic pollution affecting our rivers when new pollutants are already being incorporated that we don't even have laboratories capable of monitoring,” said Arellano.

Sampling Challenges

Experts consulted denied the common belief that a single test is capable of reflecting all types of contaminants existing in a channel.

This is how river sampling must evolve in Mexico, says Dr. Yolanda Pica, advisor to the National Strategic Program (Pronace) Toxic Agents and Contaminant Processes of the National Council for Humanities, Sciences and Technologies (Conahcyt).

“The problem with the contamination of water bodies is the way in which they are sampled. If you go to the river how do you sample, how would you go, do you take out a bottle and fill it with water and send it to the laboratory? But how much water passes through that river over the course of 24 hours. In other words, the sample you take to send them to the laboratory is a point in infinite space,” explained Pica, who has a long career in toxicological analysis at the IMTA.

In order to have representative samples, developed countries take samples through passive samplers that are placed in the water for a certain period of time.

“What they do is they absorb substances with different characteristics, it's called the partition coefficient. So there are different materials that absorb those substances and you can leave it there for a week or a month. So when you analyze what was contained there, you have a clear idea that all of this happened (in a certain period),” Pica explained.

Waste discharges to rivers and other bodies of water are regulated by the Official Mexican Standard NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021, which specifies limits for various contaminants, test methods, sampling criteria and assesses compliance with standards.

An advance of this standard published on March 11, 2022, is the incorporation of toxicity studies, understood as the degree to which certain substances can harm an organism.

However, the current NONM does not fully match the original draft of the standard, whose toxicological robustness incorporated analysis with at least three test organisms, Pica explained.

In the end, only the so-called Vibrio Fischeri was included, which uses a marine bioluminescent bacteria of the same name to identify toxicity.

“The draft of standard 001 did not incorporate only a toxicological test method, the initial project based on the knowledge of toxicology involved at least analysis with three different test organisms. Why? Because organisms have complementary insensitivities and a lot of intercalibration and studies were carried out over many years to demonstrate why these organisms. However, at the level of the authority that was Conagua, and almost behind closed doors, they decided that there was only one left,” Pica explained.

Closure of the wastewater discharge in Rio Atoyac in 2017. Photo: Profepa.

Regulatory simplification meant saving the industry in tests that require greater investment in the training of laboratory personnel. The Standard leaves private responsibility for verifying toxicity levels, since industries hire laboratories to analyze the tests of their discharges and submit such reports to the authority.

Although NOM 001 came into force in 2023, it will be until 2026 that acute toxicity studies begin to be applied.

Despite the various aspects that need to be improved, Pica is convinced that compliance with the standard will be a step forward.

“I can tell you that if it's going to be an important change to the extent that the entire industry and all municipal bodies comply with it, it's going to be a radical change in the quality of the recipient bodies, I'm sure of that, because I've been working on toxicology for 30 years,” she said.

A river of plastics

Increasing plastic pollution aggravates the problem of rivers. In Mexico, all of these water systems are around 633,000 kilometers long.

According to the National Inventory of Sources of Plastic Pollution, developed by the United Nations Organization and the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM), rivers are an important means of transporting such waste, which sometimes reaches the sea.

Inventory coordinator Alethea Vázquez Morillas, professor in the Department of Energy, Basic Sciences and Engineering Division of the UAM, said that the main cause of plastic pollution in Mexico is the disposal of waste in uncontrolled sites.

“We must remember that 17% of the waste generated in Mexico is not collected. When that happens, the population solves the problem in the way they consider appropriate, and that sometimes includes burning, burying, or simply pouring into natural space. They can be glens, rivers, vacant lots,” said Vázquez.

Once dumped, waste may leak during transport or if it is deposited in uncontrolled sites, there is a risk that it will reach the natural environment due to wind, rain and other natural phenomena.

The inventory highlights the case of Veracruz, where a 2017 study, led by researcher Laurent Lebreton, reports that the Ruiz, Verde and Pánuco rivers are “significant contributors” to plastic pollution in the ocean.

These basins are connected to densely populated cities such as Guadalajara, Mexico City and Puebla. “This leads to the hypothesis of transporting plastics (mainly microplastics) from these cities to the coast,” the Inventory cites.

Rio Blanco, Veracruz. Photo: PMA, Veracruz.

But plastics don't always flow downstream, but they stagnate.

“We have all three possibilities; that the waste remains in the riverbed, that it accumulates at the edges due to the very dynamics of the currents that we can find in the rivers and, finally, also that they reach the sea in some cases. These are all very complicated phenomena because plastics interact with the environment as they advance. Sometimes a film forms on the surface, some of them are fragmenting,” said Vázquez.

These variables make it difficult to contemplate removing all plastic waste from rivers, he says.

Causa Natura Media asked the National Water Commission (Conagua) for the list of garbage removed from the Aguas del Valle de México Basin. She answered that between 2018 and 2024, 431,817 tons of garbage have been removed, equivalent to the tons of concrete needed to build four Azteca stadiums.

It's not clear how long it can take for plastic to degrade. A scientific analysis published in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering in 2020 states that “studies on the degradation of plastics often omit key information, such as the temperature to which they were exposed, the microbial load and the size of the sample, which are essential”.

Along these lines, Vázquez elaborates: “It is very difficult to say a priori, how long it will take for plastic to remain in the sea, or in any ecosystem because it totally depends on the conditions in which it is found. It's not going to be the same if you're exposed to the sun, as if you're not and in nature, because there are going to be spaces where there's greater microbial activity or greater friction due to movement.”

“All this can have an impact so I never dare to assume a certain life in plastics in the natural environment, which we know, because there are plastics that have been in the natural environment for decades and that sometimes, even if we don't perceive them, they are there because over time they fragment, they form microplastics and that aggravates the problem,” he adds.

Plastic pollution in the La Compañía and Manzano rivers . Photo: Chimalhuacán City Hall.

In addition to the effects on ecosystems, the potential risks of plastic pollution include health effects. According to the waters concessioned for human consumption, in Mexico rivers, streams, lakes, lagoons and dams are the source of at least 61% of water for consumption, according to the Inventory.

Plastics reach the body through three main routes: ingestion of food and drink; inhalation and dermal absorption.

Studies in the United States on this problem show that the average person unknowingly consumes between 39,000 and 52,000 microplastics a year through food and beverages; and inhales an additional 22,000 to 69,000 in the same period.

One of the vulnerable foods are those related to fishing. A study by Greenpeace and several Mexican universities in 2019 found that one in five fish keep plastics in their viscera.

“Of the 755 fish sampled, 20% had plastic in their stomachs,” Greenpeace said. In the majority, at least one piece was found in their stomach contents, but there were cases of up to 45 pieces in the same fish.

“It has already been documented that people are eating microplastics from all these sources, we are drinking them and we are also breathing them because they have been found in clouds, in air, in dust. Practically, flooding the entire human body, they have been found in the brain, in the lungs, in the heart, in the blood, in the urine, in pregnant women, which means that human beings are being exposed to microplastic contamination before they were born,” says Ornela Garelli, an Oceans Without Plastics campaign at Greenpeace Mexico.

The campaign he leads is focused on avoiding the use of plastics, so the focus is on a call to reduce the consumption of these products.

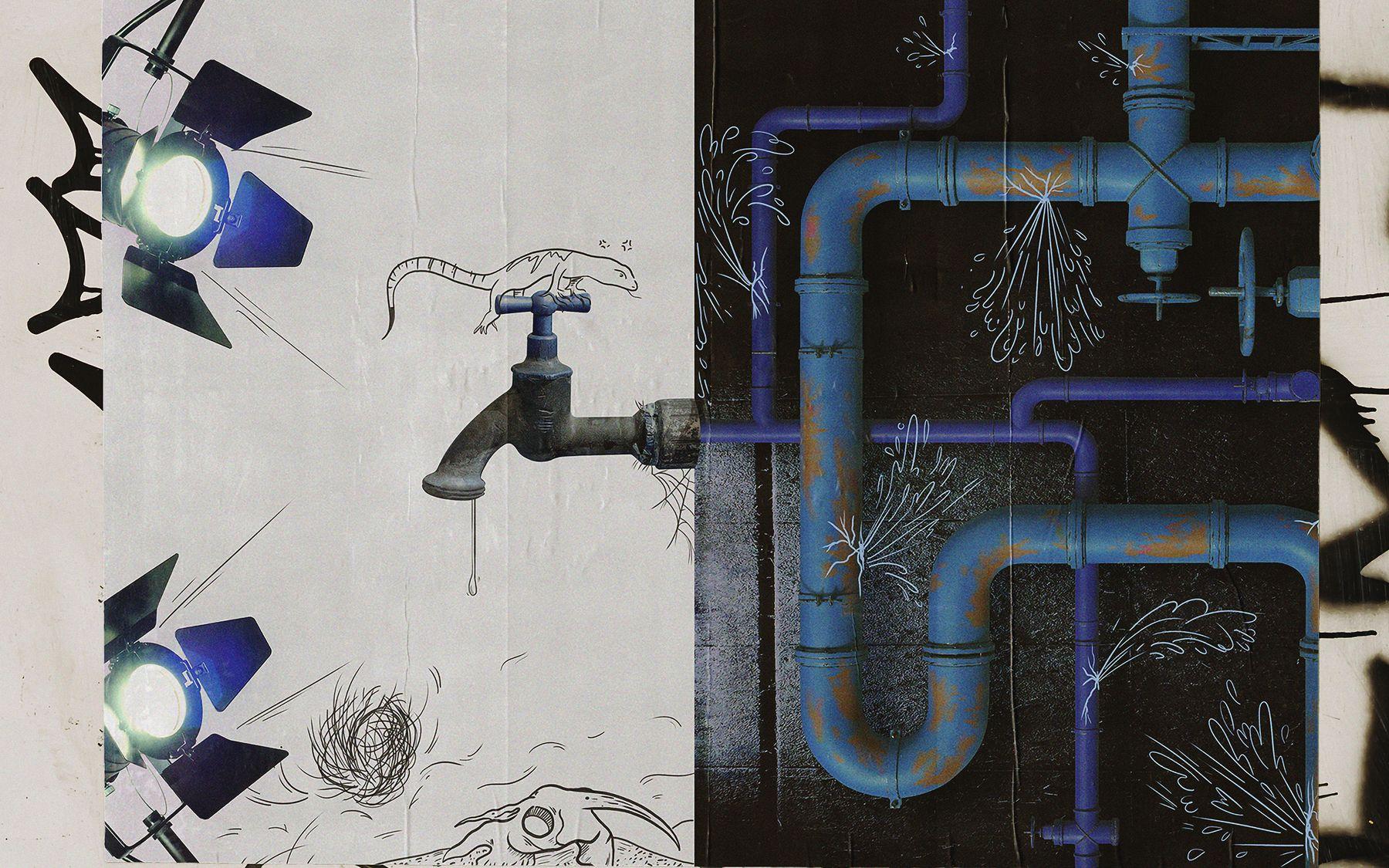

“Public participation in that is very respectable, but cleaning a beach for example, or a river or a forest and the next day is the same, again. So that's why we focus on trying to prevent more waste from continuing to arrive. In other words, we must close the key to plastic pollution, the key to the production of plastics and their commercialization,” Garelli said.

Beyond plastics, toxic substances haunt communities in Mexico.

However, the country does not have the capacity to detect what it does not register. There is a chemical control gap between Mexico and the world.

While the Chemical Abstract Service, a division of the American Chemical Society, includes 219 million existing substances and some 765,000 that are in use or regulated in the main markets, in Mexico there are 2,199 regulated substances, according to an analysis of lists contained in legal instruments shared by Pica.

Faced with the abyss of detection, Mexico could rely on the precautionary principle, an approach that advocates protective measures against suspicion of possible harm caused by products or technologies to health or the environment.

“Mexico does not have the capacity to carry out a complete risk analysis, especially following the World Health Organization protocol, which is very complex... So what is being sought to a large extent is to insist that there be a transformation in the way in which these problems are viewed and that the application of the Precautionary Principle could be useful. In other words, if in a country X or at the University where you want there is evidence that a substance is harmful, Mexico can automatically make an observation, not suspend, but an observation that its use is going to be limited until proven otherwise,” Pica explained.

Risk regions in Mexico

An effort to determine the health impact that toxic substances have had in Mexico began in the past six years through the Pronaces, which through their work have identified 70 Health and Environmental Emergency Regions (Resa) in the country.

For Andrés Barreda Marín, coordinator of Pronace- Toxic Agents and Contaminant Processes, one of the main reasons behind the effects on these regions is the industrial deregulation that occurred in Mexico, especially after the entries of North American free trade agreements and the subsequent entry into force of the T-MEC in 2020.

“What we did in Toxic Agents and Contaminant Processes was, first, to draw attention to this serious situation that prevails in the country. This scandalous institutional vacuum built by neoliberalism. Well, in reality, it began to be built before, from PRI regimes that promoted a very wild industrialization, which escalated. Mexico already had to become, under the criteria of the global economy, an attractive paradise for foreign investment,” said Barreda.

The coordinator says that the two governments of the so-called Fourth Transformation have celebrated foreign investment, but policies to protect health from pollutants are still lagging behind.

“It's not that I don't think we don't have to invest capital or that that doesn't create jobs. The problem is at what cost, the problem is under what conditions. Now Mexico is receiving a lot of requests for Mexican territories, spaces, resources and labor to be offered so that companies that are fleeing Europe or China can arrive. This wave is called nearshoring. Now let's say that there is so much demand for the Mexico brand because it would be time to put in place very strict regulations that protect the health of the population and the health of the environment,” Barreda said.

The health costs of water pollution are visible in El Salto, Jalisco, where Muñoz has counted those affected.

The town is suffering from a crisis of kidney failure and cancer, and 137 people have died this year alone, a figure very close to 147 last year.

Raúl Muñoz holds an image of the boy Miguel Ángel López Rocha who died as a result of pollution. A memorial will be inaugurated in February next year. Photo: El Salto Citizens Committee for Environmental Defense.

“It's not about them drinking water, rather they breathe it, all the time, 24 hours a day, all year round. They're breathing the gases. And sometimes you could say that they ingest it because all the food is contaminated. So that's the situation, the proximity to bodies of water,” Múñoz said.

The Committee began this count on February 13, 2008 when the 8-year-old boy Miguel Ángel López Rocha died after falling into the contaminated waters of the Santiago River.

Since then and to date, the Committee has counted 4,231 people with chronic diseases and has another list of 2,674 deaths from these causes, both of which it keeps medical records.

Muñoz said that in January he will travel to Mexico City to ask the Ministry of Health to carry out an epidemiological study of the area of the Ahogado Basin and the Santiago River.

“Because there are areas close to dams where there are more cases of kidney failure and cancer, but we want the Ministry of Health to carry out this study to locate the areas with the highest risk and treat the population before the cases are more serious; and also to find the link between contamination and the disease and death, because they seek to disqualify us, but if it happens, people are getting sick and dying,” he said.

For their part, the Resas are waiting for Claudia Sheinbaum's federal policy to use her diagnoses to implement measures to prevent diseases among Mexicans.

“A great job would have to be done in the Ministry of Health and that was starting to be done in the past six years. And I'm afraid because of the way they're talking and presenting things that on the second floor they're going to recede, they're not going to do this combined job of identifying toxic problems with priority health care problems. Hopefully I'm wrong,” Barreda said.

Before they reach the environment

Part of the problem of environmental pollution and its impacts is that pollution diagnoses do not go hand in hand with preventive actions.

In this regard, the National Inventory of Sources of Plastic Pollution is expected to be the basis for an announced National Plan of Action for Marine Waste and Plastic Pollution (Plan Remar). Although both began work together, the Plan has not been made public.

One way to force the authorities to act is through the judiciary, and civil organizations and authorities are taking the initiative. On August 15, a Collegiate Court ruled that the Congress of the Union must prohibit the commercialization and use of single-use plastics, due to impacts on health and the environment.

The amparo was filed by civil organizations in 2022. “Plastics contribute to the toxicity problem because they pollute from the moment the raw material to produce them, fossil fuels, is extracted to their final disposal,” Greenpeace said in a statement.

Currently, this organization is betting on people joining their signature to enter a citizen initiative to the Anti-Plastics Act and thus gather 130,000 that they need to present it to the Senate.

“Without a doubt, we believe that there should be legislative changes that force companies to take responsibility for this problem and just one change is our main objective of the GreenPeace Plastic-free Oceans campaign. We seek to reform the General Law for the Prevention and Integral Management of Waste, we seek to ban single-use plastics. But it should also indicate the extended responsibility of producers,” Garelli said.

Different petitions seek to limit pollution through laws. Photo: Congress Channel.

Along the same legislative path, Muñoz will ask Congress this January to reform the Criminal Code to make the contamination of bodies of water a serious crime. A measure that would imply a greater commitment on the part of industries than fines, which are paid without apparent dissuasive effects to prevent pollution, he considered.

Also in legal terms, researchers propose a legislative change regarding rivers and now see them as subjects of rights, an innovative concept of the United Nations linked to the rights of nature.

“In the current National Water Act, rivers are not considered rivers. We have studied it and unfortunately rivers are considered as receiving bodies, although they do exist as rivers, streams, lakes, lagoons, but when it comes to protection they are only considered as receiving bodies and that means that they are recipients of everything, wastewater, drainage, garbage. So that's a big problem with the current National Water Act, so it also needs to be reformed,” Arellano said.

While the debates calling for changes find sufficient support, one thing that the experts consulted made clear is that the fight against river pollution must first prevent it from reaching the water.

“It's like water is spilling in my house and I focus on trying to dry with jargon, but I don't turn off the faucet,” Vázquez exemplified.

Comentarios (0)