By Alejandro Castro and Adriana Varillas

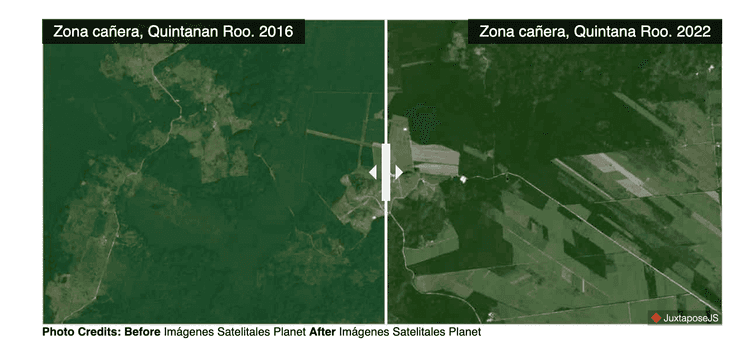

- The sugarcane zone of the municipality of Othón P. Blanco reflects the result of decades of government policies that have prioritized agriculture and livestock over jungles and forests.

- Starting in the seventies, the federal government promoted the cultivation of cane in the region. The sugar mill that still marks life in the southern area of Quintana Roo was installed there. Although many sugarcane plantations have been established since the 1980s, this monoculture has continued to add hectares inside and outside the sugar cane zone.

- In the entire municipality of Othón P. Blanco, since 2010, 75,364 hectares have been left without tree cover, equivalent to 109 times the surface area of the Chapultepec forest, located in Mexico City.

José Jesús Pérez Castro walks on the edge of the already burned plot of sugar cane, ready to be cut. May is about to end. There are no trees that provide shade to reduce the heat that exceeds 30 degrees Celsius. The proud cane producer wears a hat, dark glasses and an impeccable gray polo shirt. Ask three cutters to pose for the photograph; they, covered in tarnish and with puzzled glances, agree.

The Pérez Castro crop field is located in Sergio Butrón Casas, one of the 15 ejidos that make up the so-called “sugar cane zone”, a territory located south of Quintana Roo, along the banks of the Rio Hondo, right on the border with Belize.

Pérez Castro, like all those who plant cane in this area, sells all his production to the sugar mill that has been operating in the region since 1978. In the sugarcane field, which has no end in sight, the producer notes with enthusiasm that cane has been planted in this region for more than 40 years. And it's true.

These lands, which today form part of the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, long considered one of the critical points when it comes to forest loss, reflect the result of decades of government policies that have prioritized agriculture and livestock over jungles and forests.

Deforestation as a government policy

To understand how cane took root in the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, it is necessary to review part of the recent history of this territory.

In the seventies, during the presidency of Luis Echeverría Álvarez (1970-1976), migrants from other states of the country began to settle in the southern area of Quintana Roo. The government then promised them that if they came to populate those regions dominated by the jungle, it would give them land.

“Each ejidatario was given 10 hectares (for planting) and two hectares for livestock. It was 3,000 hectares that were knocked down to cultivate. First, rice was sown. Now, most of it is pure cane,” says ejidatario Carmelo García, who was born in 1947 in Veracruz and arrived in the area now occupied by the Sacxan ejido in January 1975.

The policy that led to the population of territories such as the south of Quintana Roo was accompanied by the National Clearing Program (PRONADE), which, between 1972 and 1983, promoted the felling of forests to transform them into pastures for cattle and fields for mechanized agriculture.

Trees surrounded by cane monoculture in Othón P. Blanco, Quintana Roo. Photo: Robin Canul.

It was in this context that the 15 ejidos that today make up the Quintana Roo sugar cane zone were created. It was also in those years that the federal government built the Álvaro Obregón Ingenio, which in 1988 was privatized and renamed Ingenio San Rafael Pucté. Thus, since the late seventies, but especially during the eighties, the cultivation of rice, habanero pepper, corn and then cane allowed large areas of the Mayan jungle in the south of Quintana Roo to be converted into agricultural fields. Today, that transformation has a different pace.

“There are no longer these big changes in land use (due to cane cultivation), but there is what I call 'ant deforestation'. Each sugar cane dismantles half a hectare, one hectare, two hectares, but if you add up what 200 cane planters do, there is an impact that is not reported,” explains Pedro Antonio Macario Mendoza, researcher on forest dynamics at the Colegio de la Frontera Sur (Ecosur).

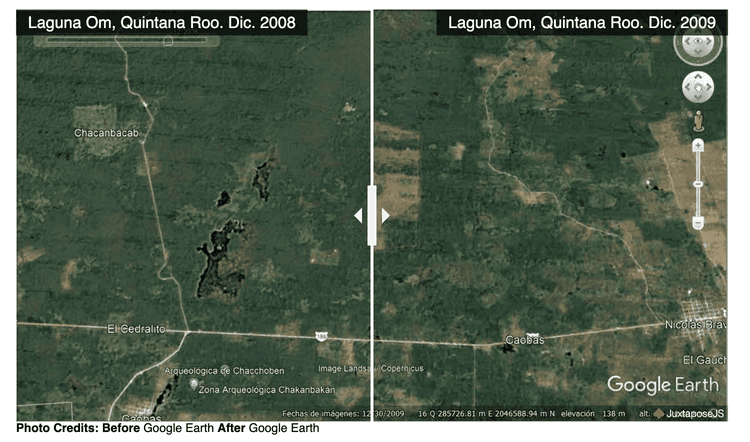

The exchange of jungle for sugarcane fields has gradually spread outside what was traditionally considered the sugar cane zone. An example of this is what happened in Laguna Om. In the forest lands of this ejido, people who presented themselves as representatives of the company that operates the San Rafael Pucté sugar mill, the sugar giant Beta San Miguel, dismantled around 2,000 hectares of low-lying jungle in 2009.

Expansion of sugarcane fields to the south of Quintana Roo.

Arriving, buying and deforesting

The Laguna Om ejido, adjacent to the boundaries of the state of Campeche, is a bastion for the conservation of the Mayan jungle, having 35,000 hectares of low and medium jungle certified as a Voluntary Conservation Area (ADVC) since 2019. In addition, the ejido is a regional pioneer in the sale of carbon credits, which seek to economically compensate the population that keeps their land intact. With all this, Laguna Om is also one of the main red spots of deforestation in Quintana Roo.

Between 2001 and 2021, this ejido was left without 9,357 hectares of tree cover, according to an analysis carried out by Global Forest Watch (GFW) and the World Resources Institute (WRI-Mexico), shared with Mongabay Latam for this journalistic project. The ejido recorded greater forest loss in 2009 and 2017.

It was just in 2009 when ejidatarios from Laguna Om and people who presented themselves as representatives of Grupo Beta San Miguel staged a conflict over the clearing of 2,000 hectares of jungle with the objective of planting cane.

In the vicinity of the archaeological site of Kohunlich, in Quintana Roo, several fires were recorded between May and June 2022 affecting forest areas that resist the advance of the agricultural frontier. Photo: Robin Canul.

Macario Mendoza, in addition to being a researcher at Ecosur, is an ejidatario from Laguna Om. He recalls that attempts to acquire ejido land for cane planting began in 2003. At that time, no agreement was reached, since the offer received by the ejido was 1,600 pesos per hectare (152 dollars, according to the exchange rate of that year).

In 2008, the then ejidal commissioner Gualberto Caamal Ku negotiated with the people who claimed to represent the Beta San Miguel Group. The payment proposal increased to 10,000 pesos per hectare (925 dollars). This is how, in the assembly, the majority of the ejidatarios voted in favor of the sale of around 2,000 hectares.

To finalize this transaction, ejido rights were sold to five people who presented themselves as part of Beta San Miguel, Caamal Ku, who is currently, once again, an ejidal commissioner, confirmed in an interview.

One of the lagoons found in the territory of Ejido Laguna Om. Photo: Thelma Gómez Durán.

Article 64 of the Agrarian Law indicates that ejido land is inalienable, meaning that it cannot be bought or sold as private property. However, what the law does allow is that ejidatarios can sell their ejido rights, but only to other ejidatarios or residents, that is, to people who have resided in the ejido for more than a year.

The representatives of the sugar company were never approached. People in the community don't know who they are. “We don't know them here, we've never seen them, everything was done through their lawyers,” says an ejidatario from Laguna Om who, for fear of reprisals, asks not to make his identity public.

Even so, ignoring the provisions of the agrarian law, the sale of ejido land took place. “They bought the rights of colleagues (ejidatarios). The assembly was informed, the assembly accepted and they made the payment,” argues Camaal Ku.

Once the deal was closed, the land buyers put machinery into the land and carried out controlled burns to enable the area to grow cane. Several people in the community, including some ejidatarios, did not agree with the irregular sale of land or with the clearing, says Macario Mendoza.

In addition to this, the clearing of the land was carried out without an authorization to change the use of forest land, a permit that must be requested from the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat). Logging without that authorization is considered a crime.

Territory dismantled in Laguna Om in 2009.

On April 15, 2009, eleven people linked to the mill were arrested, but days later they were released, according to ejidatarios. Members of the ejidal assembly had to take steps before the federal and state governments to avoid the fine imposed on the Laguna Om ejido by the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (Profepa) for the illegal change of forest land use.

The ejidatarios consulted say that the land that was left without jungle was used by the company to plant cane for a time. Today they are in disrepair.

On its website, the company Proal, Productora de Alimentos S.A de C.V., a subsidiary of Ingenio San Rafael Pucté, reports that Laguna Om also has two other sugar-producing ranches: El Corozal and Las Mil. These are located on land where rice used to be planted, says the current commissioner of the ejido. In addition, the company has the El Aric ranch, located on land in the Sabidos ejido, in the sugar cane area.

To know the version of the mill's representatives about the 2,000 hectares dismantled in the Laguna Om ejido, Mongabay Latam sought to contact a representative of the Beta San Miguel Group or Proal through different means, but there was no response. At their offices in Mexico City, at the front desk, they reported that all the staff were working from home, so there was no one to attend to the interview request.

Cane cultivation is one of Quintana Roo's main economic activities. The expansion of this monoculture has environmental consequences on the forests. Photo: Robin Canul

Stretching canaverals

In the sugarcane region of southern Quintana Roo, during the tillage period (cane growth phase), the green of the plant covers the land that in the past housed cedars, mahogany, ceibas or chicozapotes.

In the municipality of Othón P. Blanco, cane production has increased over time: if 21,784 hectares were planted in 2010, the area was 33.114 hectares in 2021, according to data from the Agrifood and Fisheries Information Service (SIAP). In 2022, 36,000 hectares were allocated to this crop, according to Evaristo Gómez Díaz, representative of the Local Union of Sugarcane Producers.

In the document entitled Analysis of Deforestation Processes in Quintana Roo between 2003-2018, prepared by the Mexican Civil Council for Sustainable Forestry (CCMSS), the Center for Research in Geospatial Information Sciences (CentroGeo) and published by the National Forestry Commission (Conafor), it is noted that the growth of the cultivated area of sugar cane in the state has been encouraged by the increase in the prices of sugar cane.

“Unfortunately, high prices encourage more deforestation,” says Dr. Edward Ellis, from the Center for Tropical Research at the Universidad Veracruzana, who for more than a decade has been studying the processes of loss and degradation of forest cover in the Yucatan Peninsula.

Producers such as José Jesús Pérez Castro, as well as the ejidatarios of Othón P. Blanco and even former officials of environmental agencies in the state, assure that the jungle has not been deforested to spread cane crops in the region. They attribute the increase in the area planted with cane to the conversion of plots that were already used to grow rice, corn and beans.

Analysis of satellite images carried out for this journalistic project shows that, in fact, many of the sugarcane fields in the region are several decades old, but it is also possible to corroborate what Dr. Macario Mendoza calls “ant deforestation”: areas of the jungle are slowly and discreetly losing ground, while cane crops gain space.

The analysis of GFW and the WRI-Mexico shows that since 2010, 33,259 hectares of tree cover have been lost in the 15 ejidos that make up the sugar cane zone. In the entire municipality of Othón P. Blanco, since 2010, it is estimated that 75,364 hectares were left without tree cover, equivalent to 109 times the surface area of the Chapultepec forest, located in Mexico City.

In this municipality, the most critical years for the jungle were 2017, when 13,122 hectares were left without tree cover, as well as 2019 and 2020, with a loss of 9,000 hectares each year.

In Othón P. Blanco, according to the Analysis of Deforestation Processes in Quintana Roo between 2003-2018, the greatest changes in forest land use were caused by the drive that the sugar mill and government institutions made to “plant sugar cane and produce cattle”.

An ingenuity that traces the life of a region

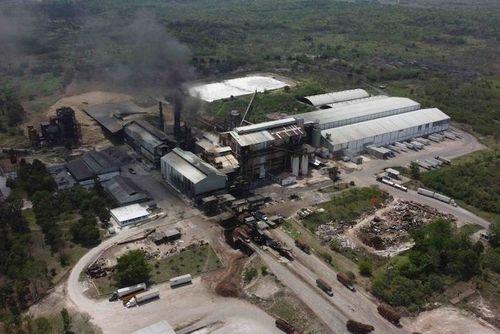

From afar you can see large fumaroles that come out of the facilities of the San Rafael Pucté sugar mill. Up close, the smoke is annoying for unused lungs.

In the south of Quintana Roo, life revolves around cane and the presence of the sugar mill that the federal government built in the early seventies, on land that was expropriated from the Álvaro Obregón and Pucté ejidos, 65 kilometers from the city of Chetumal.

In November 1988, taking advantage of the privatization process that characterized the six-year term of Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-1994), the Beta San Miguel Group acquired four mills, one of them, that of Quintana Roo, which it named San Rafael de Pucté. Today the company has a total of eleven sugar mills and is the main sugar manufacturer in Mexico.

The San Rafael de Pucté mill buys all the harvest that is produced in the town of Othón P. Blanco and in Bacalar. According to information from the company, it receives raw materials from more than 2,800 sugar cane mills and employs nearly 400 people in its plant. Cane production generates around 30,000 direct and indirect jobs in the southern region of Quintana Roo, according to data from the state government.

San Rafael de Pucté mill. Photo: Robin Canul.

In the harvest season, the mill operates every day, including Saturday and Sunday. In its facilities, cane is crushed and ground to obtain the juice that is stored, filtered from impurities and evaporated at very high temperatures to crystallize and materialize into sugar grains.

During the 2021 sugar cycle as of July 30, 2022, the mill had a milling of 1,774,069 tons of cane and a production of 183,692 tons of sugar, according to figures from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (Sader). Its yield was 54.30 tons per hectare, very low compared to 105 or 95 and 80 tons per hectare registered by mills in Puebla, Jalisco or Chiapas.

Economic agreements between producers and the mill take place under the model of “contract agriculture”; that is, both parties establish the area to be planted and the tonnage of cane that producers must deliver.

The producers sign their contract through one of the two trade organizations that exist in the region: the Local Union of Sugarcane Producers (ULPCA) and the Association of Sugarcane Producers of the Ribera del Rio Hondo.

The mill, in addition, also provides funding to producers to carry out the planting. This is through the financial company Unagra S.A de C.V. The company grants credits to producers, among other things, for the payment of cutters and to finance the “technological package”, that is, genetically improved seeds, irrigation systems, fertilizers and machinery.

A cane producer's profits depend on how many hectares he sows and the productivity of his plots, explains Martín Barajas, former secretary of the Quintana Roo Sugarcane Union. It also depends on the discounts given to you by the mill: “When you give your cane,” explains producer Carmelo García, “the ingenuity does the math and charges you what you gave it, with interest, and pays you the rest.”

Along the Rio Hondo is where the Quintana Roo sugar cane area is located. Photo: Robín Canul.

Bacalar: territory that today loses jungle

The state of Quintana Roo stands out on national maps for its forest cover: about 78% of its territory was covered by jungle in 2016, according to the most up-to-date public data from the National Forest Monitoring System. The state also stands out as one of the country's entities with a high and accelerated loss of forest.

Between 2003 and 2018, Quintana Roo lost 194,006 hectares of rainforest, an area equivalent to four times the territory of the island of Cozumel. 45.6% of that area (88.576 hectares) was transformed into agricultural land, according to the Analysis of Deforestation Processes in the State, published by Conafor.

Between 2010 and 2021, the municipality of Bacalar alone lost 84,727 hectares of tree cover, according to analyses carried out by GFW and WRI-Mexico.

The document Analysis of Deforestation Processes in Quintana Roo, published by Conafor, points to agricultural activity as the main cause of land use change in Bacalar.

The history of agro-industry in Bacalar is recent. Before 2013, this municipality did not appear in the reports of the Agrifood and Fisheries Information Service (SIAP). It was until that year that he reported having 17,574 hectares planted, mainly with corn (12,660 hectares) and soybeans (2101.50), crops that until 2021 have been the predominant in that territory where cane has also begun to have a discreet presence.

The existence of sugarcane plantations in Bacalar was officially registered as of 2018. That year, 1,160 hectares were planted. In 2021, that area decreased to 900 hectares.

The promotion of cane in Bacalar is associated with the support given to the crop by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (then Sagarpa). In a statement from the agency dated October 23, 2018, it was reported that through the Agricultural Development Program it would facilitate the acquisition of machinery, irrigation systems and technological packages.

In Bacalar, the beneficiaries of this program were the San Román and Blanca Flor ejidos (La Buena Fé). For every 44 hectares, support of 748,000 pesos (about 37,000 dollars at the time) was provided.

Cañaverales in the southern area of Quintana Roo. Photo: Robin Canul.

Weakening an ecosystem

Researcher Macario Mendoza has been a member of the State Forestry Council of Quintana Roo since 1990, as a representative of Ecosur. Within that council, he says, at different times, attempts have been made to transform some low-lying jungle lands into agricultural areas.

Approximately 14 years ago, Mendoza recalls, representatives of cane producers sought a favorable opinion from the Council for the clearing of 5,000 hectares of jungle to extend the sugar cane production area. One of the applicants represented the National Confederation of Rural Producers (CNPR) and another represented the Local Union of Sugarcane Producers. However, the request was denied.

The Ecosur researcher explains that low forests, which are at most 15 meters high, are home to a great wealth of biodiversity. “They are the best preserved in Quintana Roo and the Yucatan Peninsula, because they are flooded jungles, it is difficult for fires to progress because there is no leaf litter to burn, nor do hurricanes do them so much damage because they are shallow jungles. Now, these jungles are of great interest to crops, precisely because they are flooded and the crops require a lot of water.”

Burns in sugar cane fields and the use of agrochemicals contaminate the region's ecosystems. Photo: Robin Canul.

Trees aren't the only thing that's being lost. The medium and low-lying jungles of Quintana Roo constitute complex ecosystems. The publication Biological Wealth of Quintana Roo: An Analysis for Its Conservation, published in 2011 by Ecosur and the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (Conabio), recognizes that the deforestation process on the banks of the Rio Hondo for cane plantations has had impacts on local fauna due to habitat loss. In addition, the continuity of natural vegetation is almost completely lost in a strip that measures on average 12 kilometers wide by 45 kilometers long.

This study highlights that “this loss of vegetation connectivity has caused the disappearance of populations of endangered mammal species that were previously widely distributed in the area, such as the tapir, spider monkey, black howler monkey, night monkey and white-lipped wild boar”.

A degraded forest loses its biodiversity, but also its capacity to retain carbon and provide environmental services, warns researcher Edward Ellis. The specialist offers a fact that little is noticed when a forest area is cut down: the recovery of a mature tropical forest can take up to 70 years.

In addition to degradation, monocultures also promote the intensive use of agrochemicals.

Hands of a sugar cane worker. Photo: Robin Canul.

Eutimio Euan has been a cane producer for 24 years. He used to grow corn, but since “it didn't keep happening”, he decided to change his crop. “The cane does leave,” he says. And as proof, he says that he has been allowed to have his own house, set up a store and give his children studies.

For the cane producer, the environmental problems that exist in the southern region of Quintana Roo are more related to the use of agrochemicals than to clearing. “We had a problem,” he says, “because it was being fumigated with inappropriate herbicides that damage the earth; all that, they said, went to the streams, to the water tables, which did harm the environment.”

The agrochemical the producer is talking about is glyphosate, a broad-spectrum herbicide, considered a possible carcinogen by the World Health Organization (WHO). In the sugar cane region, they say that glyphosate is no longer applied, but other agrochemicals are used. In fact, Eutimio Euan is one of the producers who are already using drones equipped with tanks to fumigate and fertilize their sugarcane fields.

Ingenuity is also what provides fertilizers and pesticides to producers.

In his thesis Heavy Metals in Soils and Sediments from the Sugarcane Zone of Southern Quintana Roo, prepared in 2016, Gibran Eduardo Tun Canto documented the presence of mercury, lead, copper and iron in the soils of cane plots. “The Rio Hondo, which flows into the southern portion of Chetumal Bay, could be transporting waste from the sugar cane area, changing the quality of the water bodies in the basin and putting aquatic fauna and human health at risk,” the academic paper reads.

Territory marked by cane

The men covered with tarnish and bewildered eyes who agree to take a photograph with the cane producer José Jesús Pérez Castro earn their living by cutting cane. Like most cutters, they are migrants from Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche or Veracruz. When the harvest is over, most of them return to their places of origin.

In this region of southern Quintana Roo, migrants and their families who arrive for the harvest season live in galleys or quarters: camps made up of small rooms with sheet ceilings, where a small fan can do little to cool the air. Along the Ribera del Rio Hondo there are about a dozen of these galleys.

Producer Jesús Pérez Castro describes these camps as “habitable places for (the cutters) to live as a family, as if they were in their homes”.

Work in the sugar cane fields intensifies during the harvest. Photo: Robin Canul.

In one of the galleys, in the community of Sergio Butrón Casas, Roberto tries to rest lying in a hammock. He is 25 years old, a native of Campeche and a migrant. His parents inherited the job of cane cutter to him.

It's Sunday, Roberto's only rest day, and he asks to be called that. The previous six days, with a machete in hand, he dedicated himself to cutting cane from dawn until the sun announced his departure, at temperatures that went beyond 30 degrees.

“At about 4:00 in the morning you get ready; you have to make a lunch, pass the car, you go to the court and the boss starts to hit you.” This is what they call the six-furrow sections where he will have to cut the cane, with one of the three machetes provided free of charge by the San Rafael de Pucté mill or with one he had to buy, because the ones given to them are not enough for the season.

One of the warehouses where workers who cut cane live. Photo: Robin Canul.

Men end up with tarnished skin from burning smoke and their hands full of calluses. The cane, Roberto says, must be cut flush, because the candy is found in the trunk. “The payment depends on what you do. I make up to 500 to 600 pesos a day (about 30 dollars); those who don't cut much are getting 100 to 150 pesos (no more than eight dollars) a day,” he says.

The cane cutters are hired by the ingenuity. A common complaint they have is that they don't have social security. The producers say that when they receive payment for the cane they deliver to the mill, among the various things they discount is a sum of 40 pesos for each cutter they use in their fields.

Roberto waits for the harvest to finish to migrate. His plan is to travel north, try to cross the Rio Grande and reach California, United States. Unlike the migrants who arrived in this region in the sixties and seventies, or the Mennonites who buy large tracts of land, he doesn't have many opportunities to buy land and become a producer.

In this region of southern Quintana Roo, cane monocultures determine people's present and future.

When you observe this territory from above, with the aid of a drone or with satellite images, it is possible to see that despite the dominance of the sugar cane fields, the jungle still grows in certain areas that look like islands; in some areas it is a kind of wall that protects archaeological sites and cenotes.

When you explore the region by land, the fields inhabited by thin cane trunks, of the same size and similar tones, contrast with the trees that don't let the sun's rays through, vines, ground-level plants, insects, birds and mammals that give identity to that jungle that can still be found south of Quintana Roo.

*This report is part of the series Sowing Deforestation that was produced by Mongabay Latam, Animal Político and La Lista News.

Comentarios (0)