There are many occupational hazards that seafarers face every day when they go out fishing. They lay down their lives to feed thousands and despite how important their profession is, most fishermen do not have social security to protect them against accidents, disability or illness, nor are they insured for a decent retirement.

A high-risk activity

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has pointed out that fishing is one of the most dangerous professions in the world and reported that at least 24,000 fishermen or people related to fishing and fish processing die every year.

Many fishing crews lack employment contracts, do not have access to social security, pensions, health and disability insurance, and have not received basic safety training or have access to safety equipment and protective clothing that exposes them to various occupational hazards, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

In Baja California Sur, it is estimated that there are around 6,169 people engaged in fishing, taking into account the records of the Support for the Welfare of Fishermen and Aquaculturists (Bienesca) granted by the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca).

However, the exact number of fishermen who have social security at the state level is unknown. For this report, the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) was asked for the number of associated and free affiliated fishermen, but there was no response.

The most up-to-date and accessible data is on the IMSS portal, where it does not disaggregate data on membership and risks at work in the fishing sector; instead, it groups them together with other economic activities.

For example, it is indicated that during 2021 there were 18,122 people in the entity affiliated with the IMSS who are engaged in agriculture, livestock, forestry, fishing and hunting; and that at the national level there were 4,026 accidents at work related to the production of meat, fish and derivatives.

The absence of specific figures does not allow us to specify how many fishermen in Baja California Sur lack any type of protection when fishing or medical care outside the sea to help them access their right to health.

Santiago Villa, Juan Manuel Villavicencio and Jahil Villa, fishermen from the Puerto Chale cooperative in San Juanico using nets to catch guitarfish. Source: Daniela Reyes.

Contributions to the IMSS

Florencio Aguilar is the finance director of the Puerto Chale cooperative, which brings together fishermen from San Juanico and Las Barrancas, in the municipality of Comondú, in northwestern Mexico.

On April 26, the day of the interview, he had a meeting with the IMSS and is concerned. It needs 60,000 pesos to sign an agreement for a debit of 200,000 pesos held by the cooperative and thus guarantee the social security of its members.

Cooperative Societies are required to affiliate their workers and members to social security systems and implement safety and health measures at work, in accordance with article 57 of the General Law on Cooperative Societies, but they often have complications to cover with this payment.

According to José Alfredo Bermúdez Beltrán, Secretary of Fisheries, Aquaculture and Agricultural Development of the Government of the State of Baja California Sur, there are an average of 136 aquaculture cooperatives and 200 cooperative societies for commercial fishing in the entity.

Of these, you can only ensure that nine cooperatives affiliated with the Federation of Cooperative Societies of the North Pacific comply with the full membership of their members, so that they have social security during their working lives and when they retire they obtain a pension from the IMSS.

The north of the state of Baja California Sur, where this Federation is located, has species of high value, so their productions are very good and allow them to fulfill all their obligations.

This situation changes until it reaches the south of the state, where some cooperatives fulfill these obligations with many complications and others definitely do not, because it is not within their economic possibilities.

Bermúdez points out that currently there is no federal, state or municipal body that has within its legal powers and powers to monitor compliance with the Cooperative Societies Act, so everything is managed internally.

In the case of the Secretary of Labor, in accordance with the Federal Labor Law, it is only responsible for monitoring compliance with employment contracts in workplaces where there is a provision of services by workers, while in the case of fishing cooperatives, these are corporations and not companies and are therefore governed only by their own law, the General Law on Cooperative Societies.

The Federation of Fishing Cooperatives Zona Centro, for example, which groups 27 cooperatives across the state, mainly in Comondú, Loreto and La Paz, only 10 comply with registering their members with the IMSS.

Social security for access to health and pension services

Fishermen from the Puerto Chale Cooperative in San Juanico after a day of fishing. Source: Daniela Reyes.

In an intermediate experience is the Puerto Chale cooperative, which has 125 fishing members and six external workers from the towns of San Juanico and Las Barrancas, registered with the IMSS since 1985.

By joining them all, the Cooperative pays a monthly fee of around 220,000 pesos per month. In other words, of the 10 or 12 million pesos that enter the cooperative annually, 2,600,000 pesos go to cover the social security of its members.

The way to organize is simple, the fishermen go out fishing and when they return they hand over their production to the cooperative, which is responsible for marketing their products in exchange for a commission that is withheld to cover expenses such as boat maintenance, equipment, transportation, vehicles, the payment of their contributions to the IMSS and a fund for retirement, while the rest is given biweekly to the fisherman as his profit.

However, when there was greater abundance in production and poor management of resources, Florencio Aguilar mentions, the fishermen borrowed from the cooperative and lagged behind in their quotas, creating a debt with the cooperative.

This has meant that the cooperative currently has a debt of 18 million in its general finances and that only 35% of the fishermen are up to date on their contributions. The others have a debt to the cooperative that amounts to 1 and a half million pesos in contributions to the IMSS alone.

Aguilar, points out that fishermen go out to sea and do not report their production to the cooperative, because if they report it, they know that most of the money from their production will be withheld because of the debt they have and prefer to sell what they catch on their own so that, even if they pay less for their production, they keep all the profit and not pay their debt to the cooperative.

At the time of writing this report, in the month of April, it is low season and there are only 10 teams that are still working. On average, they earn 1,500 to 2,000 pesos per fortnight of profit.

The rest of the fishermen only work during the high season, which in the case of the Puerto Chale cooperative runs from October to February with lobster production and from May to July with sole production, when they earn an average of 10 to 25 thousand pesos a fortnight.

However, the cooperative has to pay the members' social security every month, regardless of whether it's low season or if all members produce or not.

Jahil Villa, a fisherman from the Puerto Chale cooperative during the off-season catching mainly guitarfish and manta rays. Source: Daniela Reyes

Now Florencio is ready to pay the 60,000 of the agreement, to pay the 200,000 he owes, but as soon as the next month starts, he has to make the payment that he risks adding to the debt due to the low production of these months.

In other cooperatives, such as Las Barranquitas, the IMSS has gone so far as to seize assets such as cars and fishermen's houses from the cooperative for the debt.

In San Juanico, they have even installed outboard motors as a guarantee of payment, however, Florencio points out that currently the threat of the IMSS is to seize the cooperative's accounts, so they sign payment agreements to avoid that outcome.

Even so, the cooperative has complied despite the complications and already has fishermen retired by the IMSS who receive 3,000 pesos and up to 19,000 pesos per month, however, the average is between 8 and 10 thousand pesos.

Fishermen who receive the lowest pensions on average have a widespread claim that what they receive is not proportional to all the risks they faced in their productive lives.

To improve this situation, strategies have been sought to increase pensions, one of the most recent and efficient of which has been to increase the contribution base from 300 to 1,200 or up to 1,500 pesos over the past five years in order to achieve a decent pension.

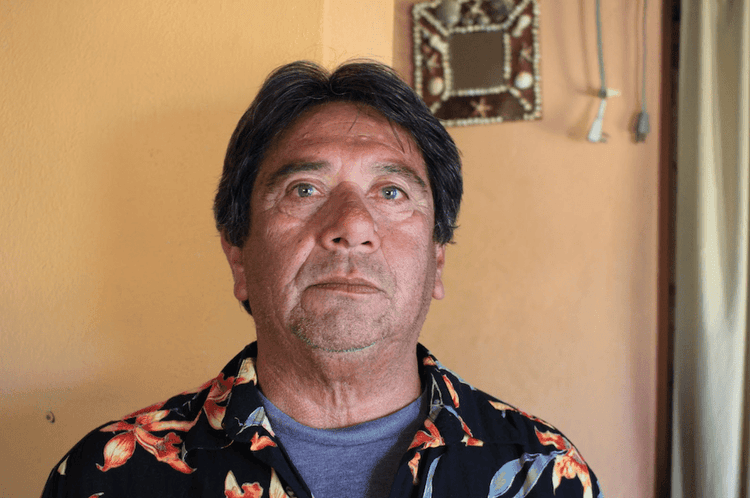

Juan Robles, known as El Piteco, is the first success story of this strategy. Six months ago, he dropped out of the cooperative, applied for his retirement fund and began the procedures to obtain his pension from the IMSS.

At 62 years old, on May 1, he received his first pension payment of 19,000 pesos, the reward for dedicating 45 years to fishing and 36 years as an active member of the Puerto Chale cooperative.

Juan Robles at his home in San Juanico. Source: Daniela Reyes

To receive this pension, Juan Robles asked the cooperative that, of the 400,000 pesos he had in his retirement fund, an amount that is given to each fisherman when they leave the cooperative, 100,000 to pay it to increase their contribution base, for this reason he reached a pension considered high.

He affirms that it is enough to support his family and live well and in peace, which is how every fisherman should retire. However, although his pension from the IMSS is resolved, the cooperative still owes Piteco 300,000 pesos, which is the rest of his retirement fund, a benefit that comes from internal finances and that, like the contributions to the IMSS, are a difficult commitment to fulfill.

Retirement: an indispensable commitment for a dignified old age

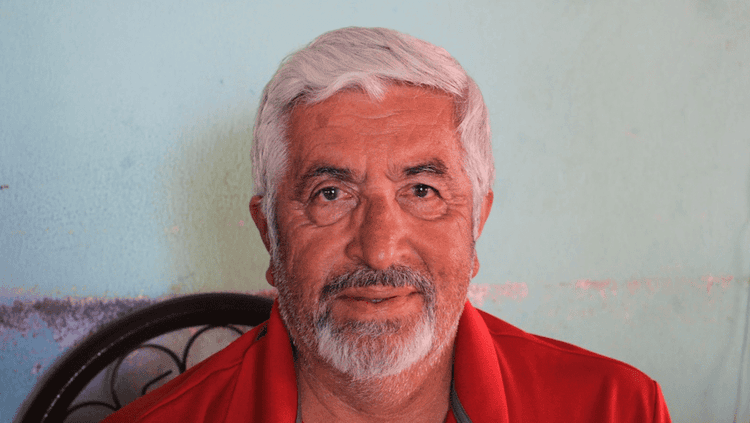

Cirilo Aguilar is, together with Juan Robles, one of the 25 members who have already applied to retire from the Puerto Chale cooperative and who are still not receiving their money. They are owed around 9 million pesos and some have been waiting for this fund for up to three years.

Article 57 of the General Law on Cooperative Societies establishes that all societies must have a Social Security Fund to cover occupational risks and diseases, as well as to create pension funds, seniority premiums and to cover medical and funeral expenses, disability benefits, educational scholarships, child care centers, cultural and sports activities.

These benefits are independent of those that members are entitled to because of their affiliation to social security systems. Each cooperative sets the amount of its retirement fund and the conditions for granting it, however, this also varies depending on your income.

José Flores Higuera, president of the Board of Directors of the Federation of Fishing Cooperatives (Fedecoop) Zona Centro, which brings together 27 fishing cooperatives in BCS and president of the Supervisory Council of the Mexican Confederation of Cooperatives (Coonmecoop), points out that the Federation of Cooperatives of the North Pacific is awarded a withdrawal of up to 4 million pesos in a single exhibition, in addition to the pension they receive from the IMSS.

However, in other regions, such as the Puerto Chale cooperative, they have established that after 20 years of work, members can request to withdraw 400,000 pesos.

Cirilo retired at the age of 65 with 2,000 weeks of contributions and receives a pension from the IMSS of 13,500 pesos, but it is not enough for him to support his house and support people who are economically dependent on him.

He owed 150,000 pesos of his social security contributions, so the cooperative owes him 250,000 pesos to complete his retirement, so he intends to pay off his debts and support his economy with his pension.

Cirilo Aguilar, retired fisherman from the Puerto Chale cooperative. Source: Daniela Reyes.

Meeting the retirement quotas represents one of the biggest challenges for the Puerto Chale cooperative, whose members are 30 years old on average.

To try to stop this dynamic that does not seem to be working, Aguilar mentions that the cooperative is working on a reform of its constituent bases to establish that the retirement fund is granted according to the production that the fisherman has had, since it is not fair to give the same amount to those who report their production to the cooperative and contribute to its livelihood as to those who do not.

Causes and ways of resolution

Juan Manuel Villavicencio and Jahil Villa, fishermen filleting and cleaning the fish product. Source: Daniela Reyes.

For any fisherman in the Puerto Chale cooperative, the reason why the cooperative has difficulty meeting its financial commitments is low production.

According to Florencio Aguilar, this is due, on the one hand, to climate change. There are more and more hurricanes in the area, whose runoff pollutes the sea and, on the other hand, illegal fishing that captures species that are banned or in sizes smaller than those allowed, affecting their reproduction.

Aguilar also points out that under the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, there were many cuts to some subsidies received by the fishing sector to pay for outboard engines and gasoline, which now represent expenses and an extra economic burden for the cooperative.

However, he does not fail to point out that this problem is also due to the attitude of the fishermen themselves who do not strive to cover the quotas, due to poor financial practices of the past. “It is their obligation to work so that the manager can get the money out of work and can fulfill their responsibility, which in the end is the responsibility of them, of the partners,” he says.

Conmecoop is implementing, in the 500 cooperatives it groups, a project to strengthen the sector in which they seek to clean up and instruct cooperatives to improve administrative and productive habits, and one of its goals is for cooperatives from the four federations in Baja California Sur to affiliate 100% of their members to the IMSS, says José Flores Higuera.

In addition, it points out that it is necessary to make amendments to the Social Security Act so that it adapts to the economic conditions of the fishing sector, so that Social Security contributions are established according to the production of each cooperative.

If fishermen aren't paying, it's for something, he points out, and the solution isn't to seize their assets, as that will only worsen the economic situation for the sector.

“I have nothing against Social Security, what I do have is that point of view. It doesn't fit me because the productive sector often cannot access that service or that benefit because of working conditions. There is no flexibility and it is not compatible with the way in which cooperatives work because if a fisherman works for six months, six months he will join the cooperative, the other six months there will be very low income, little or nothing”.

Even so, by improving administration and making the quotas to the IMSS more flexible, Alfredo Bermúdez de la Sepada, points out that it is necessary to amend the Cooperative Societies Act and empower the Labor Secretariat to review compliance with these labor rights as it did before 1994 when it was reformed.

Until actions are taken to remedy the right of fishermen to social protection, as mentioned in the Decalogue for the International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture in Mexico, this debt of the Mexican State to those who make up this valuable fishing network, which despite providing welfare to society, is not assured of social security or a decent retirement, which places them in a situation of vulnerability.

The same decalogue states, “physical integrity at sea and unit of production must be a matter of State and law that concerns all of society”.

Comentarios (0)