The idea of a virgin and exclusive beach in the middle of the desert has led Baja California Sur to a progressive process of privatizing beaches through the blocking or control of access and use, displacing locals from enjoying these resources by private individuals and their real estate projects.

This year, prior to Holy Week, the City Council of the city of La Paz, the state capital, launched an inter-institutional program with all three levels of government to respond to reports of access to beaches that are public roads and are blocked or controlled, said Pavel Castro, general secretary of the institution.

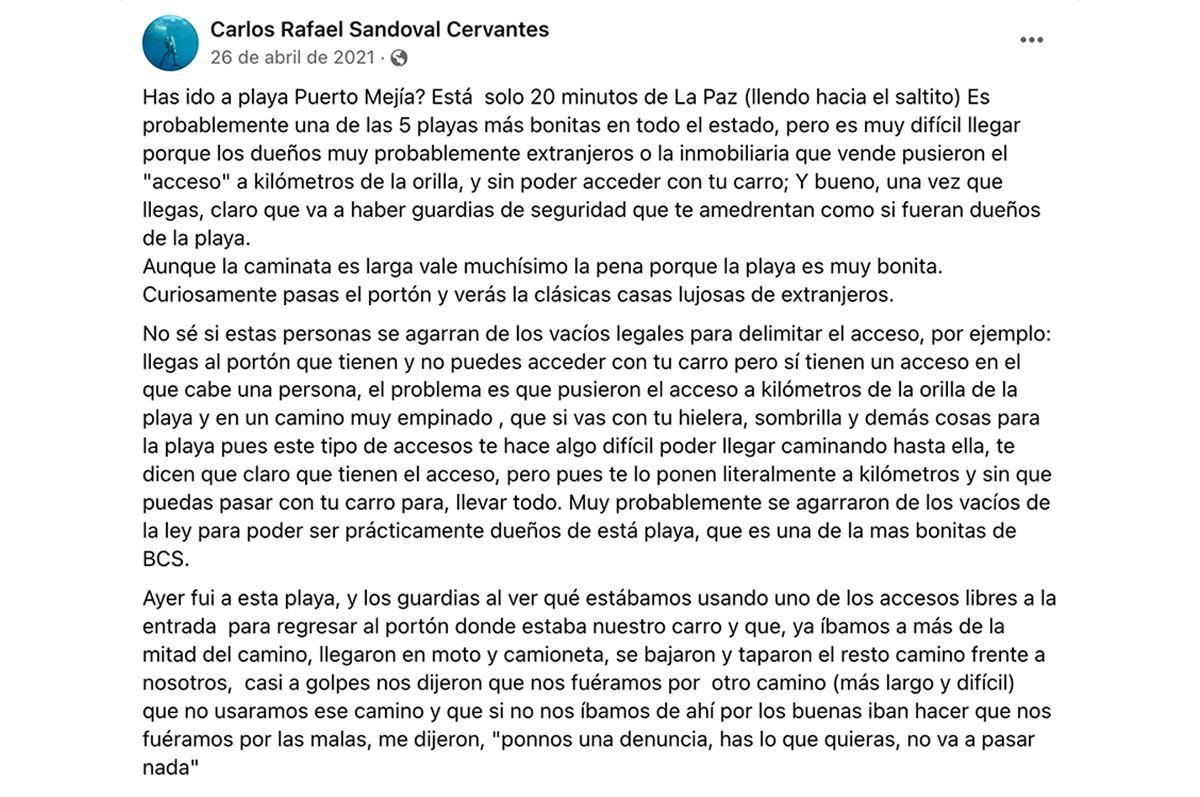

Among the reports, which number around 27, stand out that of the beaches of Puerto Mejía and the bypass that leads from the road to access the beaches that are located from El Saltito to Las Cruces, with which a long road has been taken to liberate them because there are resistances that threaten to close them again as soon as the authority retires.

South Californians have historically defended beaches and their struggle has been recorded in documentaries such as Baja All-Exclusive, which for 12 years warned about the flip side of tourism projects, the one that robs locals of their coastal heritage and way of life.

Privatization of beaches and the price of exclusivity

“National assets belong to everyone. The beaches belong to everyone and in that sense they must be public and no one has the right to buy or own them,” Castro points out, in accordance with article 127 and 8 of the General Law on National Assets.

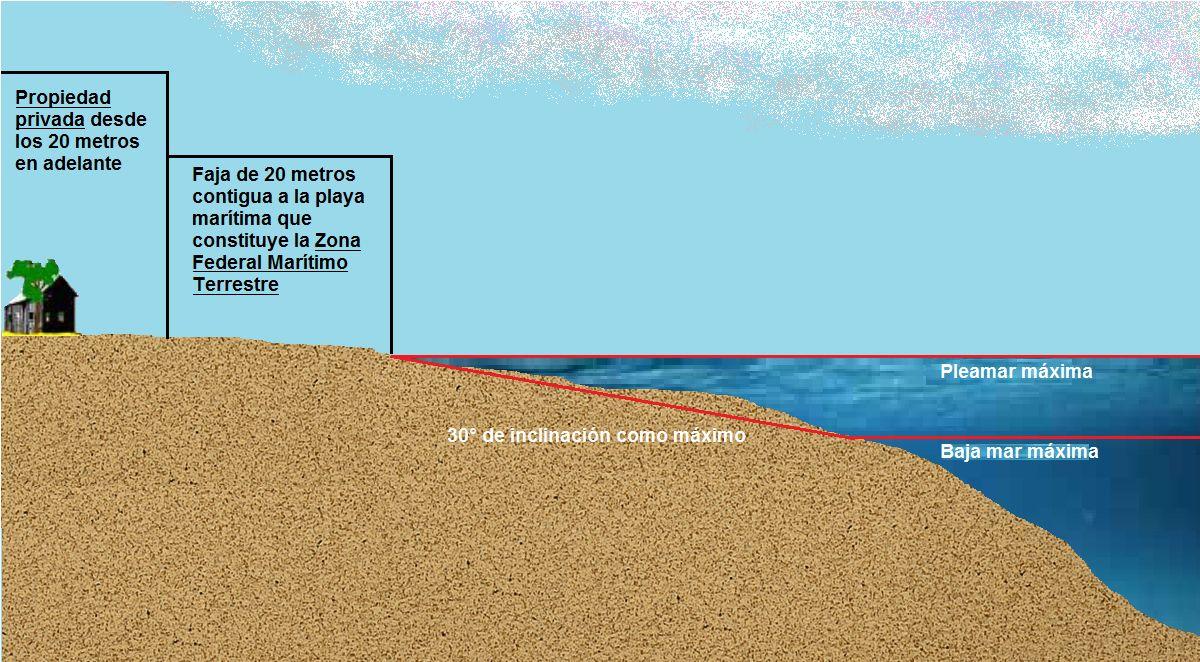

The Federal Maritime Terrestrial Zone (Zofemat), according to its regulations, is the twenty-meter-wide strip of dry land, passable and adjacent to the beach, while the beach is the part of land that covers and uncovers water due to the effect of the tide.

The Law establishes that access to both may not be inhibited, restricted, hindered or conditioned except in cases established by the regulation and that in the event that there are no public roads or access from public roads, the owners of land adjacent to the Zofemat must allow free access, through easements of passage (permits to travel) and which must be defined with the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat).

Access, whether easements of passage or neighborhood roads, which are also public goods, must be respected and at no time incorporated into private property, in accordance with the law.

“This must be sanctioned and regulated before it happens,” said Carmina Valiente, a research professor at the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur.

Obstructed roads

In Puerto Mejía and on the El Saltito-Las Cruces road, it was identified that obstructed roads are public roads because they are neighborhood access in the first case, and because they are the northern bypass of the crosses in the second, whose registration is in the National Road Network.

The bypass connects the road to the beaches but it is also the access to two properties, one in El Saltito and the other in Las Cruces. This road was hampered by two feathers to limit access. According to Pavel Castro, this road, even if it is within the properties, is the property of the State Road Board.

Castro explains that in order to respond in a timely manner, an entire legal analysis was carried out and an inter-institutional operation was integrated between Semarnat, Conagua, Zofemat La Paz and Bienestar, who represented the federal government; while the municipality was carried out by Municipal Transit La Paz, Cadastre and the legal management of the City Council of La Paz.

Through this operation, three beaches (El Saltito, El Carrizalito and El Carrizalito 2) were released. The first feather was removed in the El Saltito estate, where Castro mentions that access to a stream considered a federal zone by the National Water Commission (Conagua) had also been obstructed, and which leads to the beach, with palm trees, metal fences and barbed wires.

Prospero Tapia, who identified himself by telephone as the representative of the company that owns the El Saltito property, and is President of the College of Architects of Baja California Sur according to his website, pointed out that the City Council of La Paz acted abusively, partially and “outside of any regulations without being the competent authority”, since he maintains that it is an easement of passage that connects only El Saltito with Las Cruces and that it is on private property.

“They are seeing that it is a road that connects within their own land but that's not the case, it's a road that leads from the beach to the road,” Castro said.

Tapia clarifies that at no time have they opposed people entering the beach, but he advocates that it be a regulated use such as Balandra Beach, which he also sees as impractical due to the lack of presence of the authorities, he said.

“Now we have people who, unfortunately, many are people with little ecological conscience, and they go to the beach with vehicles where the turtles are spawning and they don't care about anything and then you have to be fighting with them.”

Las Cruces

The second gate in Las Cruces was also removed and now there are security guards and chains that control access. Even the owners of the property filed an amparo lawsuit that was denied to them by the Federal Judicial Council (CJF) and the right to access national property was ratified.

For this report, Causa Natura Media contacted the legal representative of Rancho Las Cruces and requested an interview through the phones on their website, but they did not respond.

“We knew there was going to be resistance because for 10 or 20 years they got used to a privilege, to exclusivity,” says Castro, who is currently facing two complaints from disgruntled landlords who accuse him of abuse of authority and dispossession in operations.

“We know that we are going to win, we have legal reason, even social reason and justice on our side.”

In turn, the City Council of La Paz has filed complaints with the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection (Profepa) for checks to be carried out, while waiting for the sanctions to be imposed by the competent authority that is Semarnat. “The fine ranges from approximately 300,000 pesos to the loss of the concession, but it already escapes our jurisdiction,” Castro explained.

Valiente points out that in the discourse, since they are public goods, they cannot be privatized, but in practice they can be done through the inappropriate use of the concessions of the Federal Maritime Terrestrial Zone and through the closure of accesses or the control of access to the Zofemat and the beach.

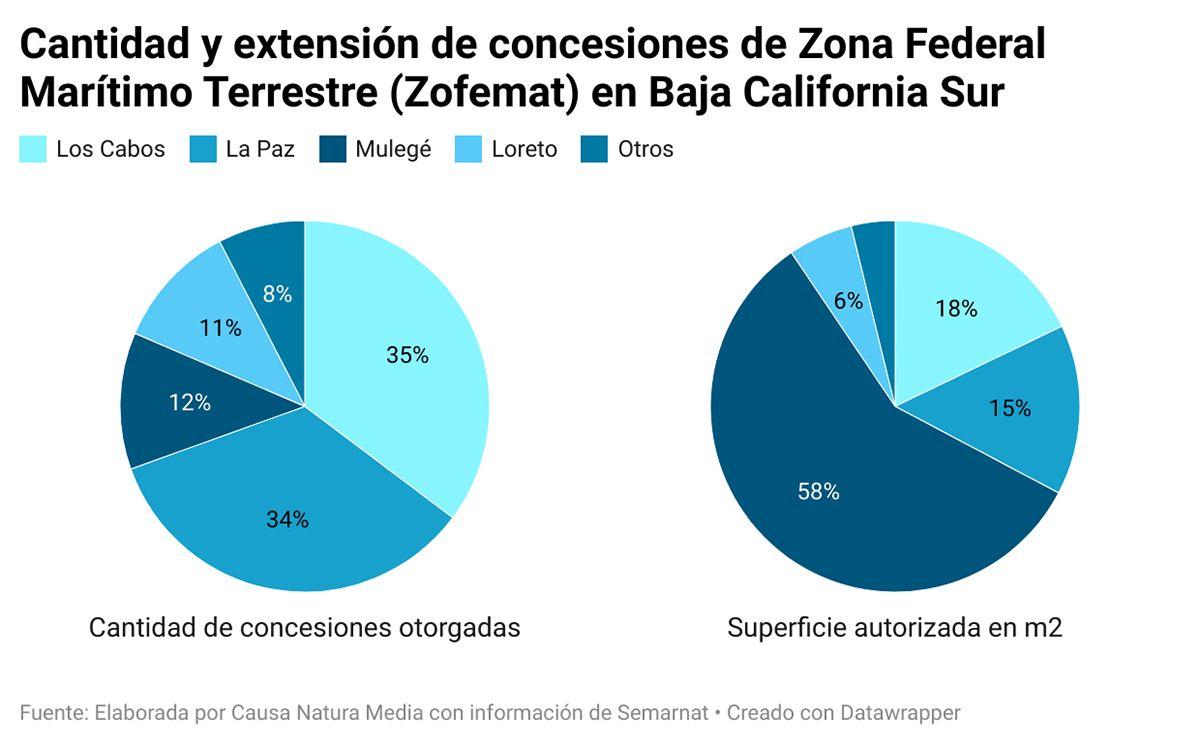

In Baja California Sur, there are 210 Zofemat concessions that represent 2 million 967 thousand 489 square meters of surface, according to information provided by Semarnat through a request for information.

Those who have a Zofemat concession or have a property adjacent to the beach often “feel like they own the beach,” said Valiente. This is a commonly used space, which is important to defend because you don't just have a right of access.

“Without access there is no right of use and the quality of that space is not guaranteed,” said Valiente, pointing out that Zofemat dealers have the exclusive right to profit from the use of the beach, but that doesn't mean they can deny access and use of the space.

La Paz has 72 Zofemat concessions that correspond to 399 thousand 669 square meters of surface, of which 46% are granted for authorized tax use for protection, followed by general use (7%), fishing (2%) and ornamentation (2%). In the case of the use of protection, dealers are obliged to keep the Zofemat clean, because that's what it was given to them for.

Ecological protection?

Pavel Castro points out that the licensees' main argument for limiting access and the right to use beaches is the pollution generated by those who visit them and by the entry of vehicles. Since the dealers have an obligation to keep the space clean and if they don't, Profepa has the obligation to remove the concessions.

“When the concession is lost, someone else can request it and that represents a risk for those who profit from the beach, or for those who want to preserve it against the profit interests of others. This gives the dealer the justification to prevent, if possible, or limit access to the beach through a narrow road, a parking lot and setting schedules, as if they owned the beaches, but that's illegal,” Valiente said.

Because it is an asset that belongs to all people in Mexican territory, the State has an obligation to manage and protect it for the common good, but if it doesn't, private individuals occupy this place, he argued.

“And this is happening because beaches have become a business for the tourism industry and especially real estate related to the tourist valuation of a territory,” he added.

|  |

|  |

In the case of Puerto Mejía, west of El Saltito, it was reported by fishermen and visitors who went to the area and had limited access to a neighborhood road that leads to the beach. The City Council of La Paz removed the gate, however, the owners of the land adjacent to the Zofemat filed an amparo that has not yet been resolved.

In the same way, the legal representative of the owner of the property in Puerto Mejía was contacted to give his version of the events. He asked for the anonymity of his name and replied that “whenever this matter is in a judicial proceeding, we consider that the time was not right to make a statement.”

The Price of Exclusivity

“Exclusive oceanfront beach resort in Baja located in a natural sanctuary of more than 10,000 acres and 7 miles of private pristine coastline,” reads the website of a hotel located in Las Cruces.

The interest in having private use of beaches comes from the tourist-hotel sector, which wants its customers to enjoy exclusive use of them, Valiente said.

However, the model of coastal growth has changed and today there is pressure for an urbanization of the coastline with tourist residences or second homes, whose owners also want to enjoy exclusive use of this space, he said.

In Las Cruces, Castro points out, these are owners of large land and with large capital who “somehow sell the idea of exclusivity and then their land acquires greater value, well, we will have to find the middle ground, between offering development and also the enjoyment of the beaches”.

“The beach is a natural resource that generates multi-million dollar profits. It is an exchange value that is invisible. It is a natural resource that generates income for the government, for the real estate sector and especially for the hotel sector and the tourism sector. In short, the beach has become a business, as a natural resource, as a natural system, as a landscape,” said Valiente.

For this reason, he points out that there should be a delimitation according to the value of use, since if there is a high demand for space by so many sectors, the Zofemat should be expanded and not restricted to 20 meters, especially in a space where the well-being of the population depends on the access they have to the sea.

Legal loopholes for managing beaches

Semarnat is responsible for delimiting the Zofemat while Profepa is responsible for managing the space in terms of management and care. In the case of beaches, when you are without a dealer, it is Profepa who is responsible for managing them, guaranteeing access and keeping them clean.

On the other hand, if there is a dealer who pays for the exclusive right of profit to the beach to the municipal management of Zofemat, it is the dealer who is responsible for this.

Valiente emphasized that there is no ecological management of beaches as such and their protection as a natural system needs to be integrated into ecological management programs and partial urban development plans.

In addition, the delimitation of the buildable space and the Zofemat, which is an ambiguous and variable delimitation, are insufficient to prevent erosion processes.

Since these management tools do not exist or are not clear, they favor leaving it to the grantees to manage the common good when it should be co-management, because it is a commonly used resource or the loss of it, he said.

Fines and penalties

The Criminal Code for the State of Baja California Sur establishes three to seven years in prison or a fine of one thousand to three thousand days for anyone who closes, obstructs, destroys or prevents access to beaches or federal maritime-terrestrial zones, but in the application of the Law there are failures on the part of Profepa, there are no consequences and that discourages reporting.

“At Easter, given the high demand for use, municipal and federal governments are starting to release beaches to make the news, because they know that people are going to demand their right. Often after Holy Week they forget everything. There must be a constant exercise to ensure the maintenance of public goods. That is the function of the State. But most of the time, what happens with complaints about beach closures is that there are no consequences, and that's why we get tired of wasting time reporting,” he said.

And in part, he pointed out that this is due to a lack of clarity in the legal competencies and competence of each authority, as well as to institutional weakness.

“This municipal government (La Paz), also freed beaches before Holy Week. In part I think that because it gives political visibility to the municipal government, but also because it is responding to a need of the population. The important thing now is that this orientation towards the preservation of the public be continued,” said Valiente.

However, Castro pointed out that although it is currently being promoted as a public policy, he expects next year to promote it as a budgeted program and that it will continue with a second phase in which they will review and give certainty to legal loopholes that they have identified in regulations and laws to defend national assets.

It also points out that it is necessary to attend to the accesses that are inside the properties and that must be established with Semarnat, since that currently only depends on the will of the owners.

“If I (the owner) don't define access to Semarnat and I don't register it here in Cadastre, then 10, 20 years can pass and I never made access to the beach and let's just say that the city council is not empowered to say, “register it, right now”, it's Semarnat's power, but we don't want 10, 20 years to go by without that happening,” Castro said.

Despite these loopholes, Castro points out that in no way is anyone going to be invaded or robbed of their assets, he is simply trying to reconcile access and free passage of beaches and the real estate and hotel sector.

As a natural system, landscape and essential space for access to the sea, beaches are a finite and non-renewable resource. When they are urbanized, they are lost forever and in fact, Valiente points out that in BCS there are kilometers of coastline that have already been lost because they were urbanized. This is the case of Los Cabos, where you can't even see the sea because it's been walled up.

“With this loss, we are also losing food security, the possibility of accessing maritime resources, and that is very serious”

Organized resistances

|  |

Now that the accesses are open, people are exploring new beaches that had been closed for years and authorities such as Zofemat can finally access them to do cleaning work because “it was private property”.

The defense of public beaches is a movement that mobilizes and is easily articulated to take action, for example, through Facebook groups such as Playa para tod @s, where more than two thousand people share complaints about possible privatization of beaches.

“It helps interested people like me to have together publications, complaints and all the information related to beaches in Baja California Sur, especially in La Paz,” says Valiente, founder of the initiative.

This struggle has also permeated culture, even generating music around these resistances, such as the song Baja Love by the South Californian band Venados Muerto, which criticizes the development model.

However, Valiente pointed out that educational campaigns are needed to raise awareness about beach care, as is done for other ecosystems such as mangroves. In this way, citizens can also get involved in co-managing this space, taking care of it and keeping it clean.

“Because if we delegate it to the government and private property, then they will start to set rules in their favor and that will harm us. If we get involved, we can sue, we can demand our right,” says Valiente.

Comentarios (0)