Shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic, Hugo Ávila, also known as “El Xocoyote”, a resident of the San Martín Texmelucan municipality, in Puebla, started cleaning brigades for the higher regions of the Atoyac River.

“Doing something on our own” is how Ávila defines it, who is in charge of using his van as a transport, while the rest of the volunteers from the well-known “Xocoyote herd” carry their own tools for collecting solid waste.

However, it recognizes that there is still no work to mitigate the impacts of the main cause of pollution: industrial corridors.

The wastewater that is discharged from industries, together with garbage and municipal drainage from cities, has caused the Atoyac river that runs through Tlaxcala and Puebla to be painted in different colors for more than 30 years.

It can be brown or yellow, sometimes dyed red and, at other times, a blue that turns to purple. An effect of the untreated mixture of heavy metals, hydrocarbons, drugs, detergents, plastics and textile pigments that are discharged into the river.

“A river of colors, like a rainbow”, describes “El Xocoyote”.

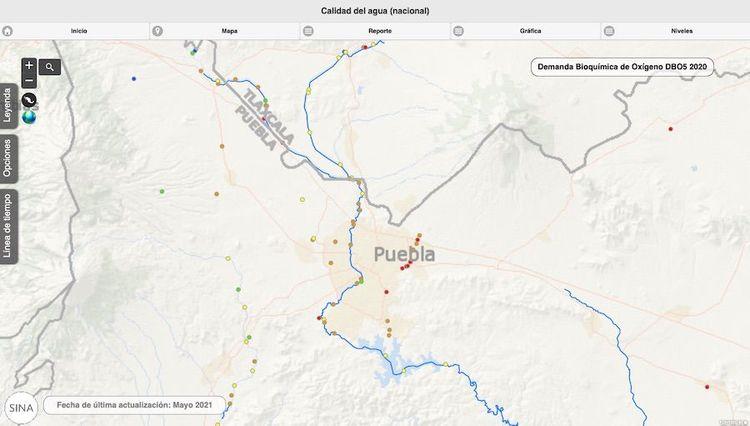

Water quality in the Atoyac River up to May 2021, mostly marked as orange for Contaminated classification and red for Strongly Contaminated. Source: General Technical Subdirectorate of Conagua.

White elephants

The Atoyac Basin, as well as the Valsequillo Dam, are the most polluted regions in the area, according to the 2012 - 2020 diagnosis of the National Water Commission (Conagua). This includes tributary rivers such as the Zahuapan, Xochiac, Atenco and the Atlapitz and Honda ravines.

One of the solutions proposed by the authorities has been the installation of wastewater treatment plants.

“In the Atoyac river basin there are more than 10 treatment plants for domestic water, when the source problem is the industrial one. They are white elephants that were left abandoned for years. They don't work because they are not supplied with money, equipment, qualified personnel,” explained Omar Arellano-Aguilar, a researcher in the Department of Ecology and Natural Resources of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

In addition, agreements have been signed and resources have been granted to recover the Atoyac River and the Valsequillo dam. The last was an agreement between the federal and state governments of Puebla and Tlaxcala, signed last September as a response to the recommendation for damages issued by the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) since 2017.

With the signing of the agreement, there was also talk of starting work on a sanitation model that, until now, has not had updates.

“The problem is that government proposals are uncoordinated. They are not addressing the root of the problem that is the industry and they are not allowing the active participation of communities,” said researcher Arellano-Aguilar.

For more than 30 years, groups, universities and civil associations have registered the loss of biodiversity and diseases such as cancer, anemia and kidney failure, as a result of exposure to carcinogenic and neurotoxic chemicals. But despite the information, the sectors agree that to date there are no effective current solutions.

Photo: Francisco Guasco/cuartoscuro.com

Denim water and other damage

If you are looking for documentation on the impacts of industrial pollution on the Atoyac River, there are records of environmental and health damage since the beginning of 2000. Although the precedent is in the 90s with the rise of more sophisticated industrial corridors.

From small to large industries, they have built along the river. The automotive industry, which was a pioneer since the 80s with the Volkswagen Plant in Puebla, aroused the interest of other industries such as textiles, petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals.

“It is a model of an industrial city that originated in Germany, in Europe, and was implemented here to generate industry and concentrate on different industrial sectors within a single territory,” said the UNAM researcher.

Currently, there are an estimated 2 thousand 15 economic units per industrial sector, in accordance with the recommendation of the CNDH. Some of those listed are the Skytek and Globaltex textiles; the Big Cola soft drink; the chemical and pharmaceutical company Bayer.

“Each part of the Atoyac has a different degree of contamination. It is not the same with San Martín Texmelucan as in the towns closest to the mountains or the forest. Each part has its difficulty,” Avila explained.

20 minutes from the river, San Martín Texmelucan has become a region of textiles, paints and petrochemicals, where denim is at the center of production. But, just as the manufacture of pants began, waste to dye clothes began to be spilled.

The color of the waters, as blue as denim, led UNAM researchers to analyze that the corridor emits high concentrations of chloroform, dichloromethane, zinc, chromium, aluminum and nickel.

Concerns increased when studies showed diseases such as hemolytic anemia and kidney failure in women, boys and girls.

“We have data from colleagues who work in this region that people in the area are suffering from health problems and the presence of heavy metals in their blood and urine,” Arellano-Aguilar explained.

“In order for us to recover the Atoyac, the first thing we have to do is stop industrial and urban discharges that are discharged raw or with little treatment into canals and the main channel. Make ecological orders that slow down these processes and give them a different dynamic,” said the researcher.

“The industry has been very voracious and corruption has allowed companies to settle and cannot close them... All I see is that there is more and more pollution, and I think that politicians believe that the planet has no limits...”, says Ávila as she drives through the streets of San Martín Texmelucan.

The Xocoyote herd, he says, has not yet reached the areas of greatest environmental deterioration where industrial corridors are concentrated. But he assures that, when the time is right, they will also be ready to request a dialogue with company managers.

“With our work, we also want to show the same government that the population can put their will, that we know the remedies and that they act that way,” he says.

Comentarios (0)