Number 42 of the Azteca Stadium Circuit is the entrance to a wooded and unpaved building behind the Santa Úrsula park, in Coyoacán. The security guard at the entrance explains that the place is a nursery, but he says he doesn't know that this area could become a commercial and hotel mega-construction.

The Azteca Stadium Complex, its official name, is a mixed-use project that consists of a four-level shopping mall, a seven-story hotel, as well as a parking lot on the sidewalk and basement.

The purpose is to be ready for the 2026 World Cup, which will take place in Mexico, the United States and Canada.

The two properties on which construction is planned belong to the company Televisa. The first building is located in Calzada de Tlalpan 3475 for the remodeling of the Azteca Stadium and the second in the Santa Úrsula park area for the shopping center, about 10 meters from the current stadium parking lot.

Last October, Claudia Sheinbaum, head of government of Mexico City, reported that a neighborhood consultation would be held so that the population could learn about the impacts of mega-development and give their opinion on the matter.

One of the main concerns that has arisen among residents is that the operation of the Azteca Stadium Complex will require more than 567,731 liters of water per day (207 million liters per year), according to the Environmental Impact Statement (MIA) of the project that is currently under review.

The requested daily consumption is equivalent to the average use of 5,670 people per day in an area where water is received by tanking. Added to this is the removal of 582 trees, the damage to more than 34,000 square meters of green areas and the impacts on mobility for streets with regular traffic.

Azteca Stadium Circuit, number 24. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

“Water is one of our main reasons for mobilization. We are from the neighborhoods that have a fairly spaced tandeo (supply by schedule). In hot weather, it really is difficult to have access to water, it can be up to once a week, more or less,” explains Natalia Lara, 29, a member of the Tlalpan Coyoacán Assembly against Megaconstructions.

“People have become used to living with the minimum, which is a violation of the human right to water,” he adds.

Natalia, like her neighbors in the Pedregal de Carrasco neighborhood, had heard about the possibility of construction at the Azteca Stadium, but she officially found out last October, when information modules and pollsters arrived for the neighborhood consultation.

Although it was reported that the project is expected to consume 207 million liters per year, it was not mentioned that the property already has a concession from the National Water Commission (Conagua) granted to Televisa since 2019 for the equivalent of 450 million liters per year.

This information was shared by the Tlalpan Coyoacán Assembly through the publication of a Counterreport that includes part of concession title 811078.

They decided to call it Counterreport because it is the technical answer to the studies that are being carried out to obtain permits and authorizations for the work. For example, the MIA and the Urban Impact Opinion, which are currently under review.

The person in charge of technical studies by the Azteca Stadium Complex is Plumarc, a consultant who has also been hired for complexes such as Mítikah, a mixed-use construction with a history of temporary suspensions during construction in the town of Xoco, Coyoacán.

In the case of the Azteca Stadium shopping mall, in order to extract the 207 million liters of water that are being requested annually, drilling a well is proposed as a mitigation measure.

“An extraction well with a capacity of 2,592 million liters per day that will be managed by Sacmex (Mexico City Water System) on a 400-square-meter piece of land donated by the developer on the Azteca Stadium Circuit street,” the site states.

With this level of extraction, the Azteca Stadium Complex will receive 21.9% of the capacity for the operation of the mall and the rest of the extracted water will be sent to the public network.

Regarding the availability of the water that will fill the well, no authority or developer has given details.

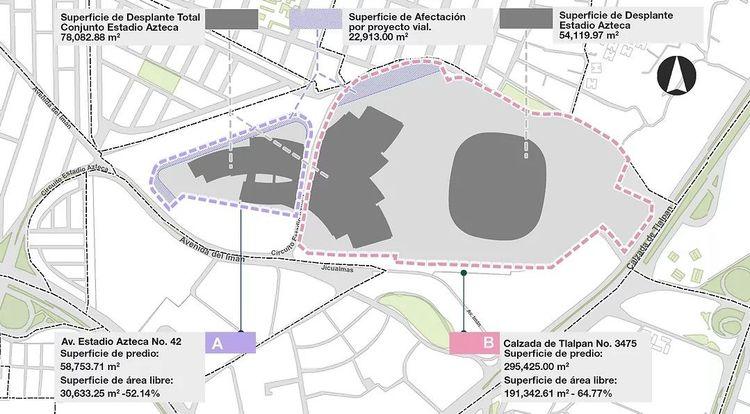

Project construction sites. Image: Azteca Stadium Complex Neighborhood Consultation.

The users of Conagua

Televisa's concession of 450,000 cubic meters of groundwater per year is in sixth place on the current list.

For Mexico City, a landlocked basin, groundwater is the most important because 75% of the capital's supply comes from what is extracted from them.

Mainly from the aquifer of the Metropolitan Area to the southwest, which is currently in a state of overexploitation.

As for the list of current concessions, the first place in volume goes to Capricho Habitacional for 2 million cubic meters per year in the Álvaro Obregón mayor's office. That's 2 billion liters, considering that each cubic meter is a thousand liters.

Following the coordinates registered in the REPDA, Capricho Habitacional is a wooded and fenced plot of land in Santa Fe, which is located next to the High Park Reforma apartment tower.

This concession is followed by Embotelladora Mexicana de Beverages Refrescantes, S. de R.L. de C.V. with 1 million 128 thousand cubic meters per year in the Cuauhtémoc mayor's office; Procter & Gamble (P&G), owner of brands such as Pantene, Ariel and Downy, with 551,000 cubic meters per year in Azcapotzalco; and the Comercializadora de Dairy y Derivados, S.A. de C.V., a subsidiary of Grupo Lala, with 551,888 cubic meters in Azcapotzalco.

In the list, following the coordinates of the concessions, there is also the Torre Monet residential complex, located in Plaza Carso, with 223 thousand 665 cubic meters; and the Plaza Tepeyac in Lindavista with 99 thousand 690 cubic meters per year.

All of the above are concessions for groundwater.

“We are in a water crisis and it is attributed to climate change or to the fact that there are many of us (in population). That has to do with it, but it also has to do with the lack of planning with regard to what is available,” explains Carlos Vargas, member of the National Coordinator Water for All, Water for Life.

For the past two years, the Coordinator has been working with the concessions granted by Conagua to identify the main users.

Although the project is still under development, so far they have located mines, bottling plants, paper mills, real estate, shopping centers, textile and automotive companies as the users of the largest volume of concessioned water in the country, both underground and surface.

Mítikah, the hidden giant

While the works are being reviewed in the Azteca Stadium Complex, north of the Coyoacán mayor's office, there are others that are about to be inaugurated.

Real Mayorazgo, the cobblestone street at the exit of the Coyoacán metro where the town of Xoco is located, is now a new concrete corridor that contrasts with cobblestone houses that have always been there.

There are signs, black work and dozens of workers wearing phosphorescent vests and construction helmets. The sound of drills and machinery operating is combined with that of traffic on the avenues.

The changes are the result of the Mítikah project by the developer Fibra Uno (Funo). A 267 meter high tower located on Avenida Río Churubusco 601. Its 62 floors offer apartments for housing, work offices and a shopping center scheduled to open in September.

The project began 13 years ago, but the mobilizations of the town of Xoco, who were demanding the urban and environmental impacts of the work, managed to extend the process.

The first complaint was the demolition of 119 trees, as well as the unauthorized felling of 80 for which the company received a fine of more than 40 million pesos.

After a series of provisional suspensions, the last one granted at the end of 2021, circuit judges decided to rescind them, arguing that Mítikah meets all legal requirements for its construction.

“It's been a constant. For more than 10 years we have been making several complaints and resorting to legal instruments of all kinds, but mega-developments continue,” says René Rivas, who was legal advisor to the town of Xoco since the beginning of the meetings.

Faced with this scenario, Rivas summarizes that the neighbors are divided between those who consider that Mítikah is an economic opportunity, and even sold their property or are working on construction, and those who have positioned themselves against the project where one of the main issues is the supply of water.

Despite multiple meetings with authorities such as the Secretariat of the Environment of Mexico City (Sedema) and official documents published for public consultation, there is no data on the amount of concessioned water that this project has, whose dimensions double those of the current Azteca Stadium.

“The issue of water is something we get tired of asking, meeting after meeting, request for information after request for information, and to this day it has not been clarified for anyone how much concessioned water Mítikah has,” Rivas points out.

Works by Mitikah on Calle Real de Mayorazgo. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

What is known about Mítikah and the use of water is that there is a Declaration of Environmental Compliance for the construction of a well that will have an annual extraction of 946 million liters per year, whose operation will be carried out by Sacmex.

As in the Azteca Stadium megaproject, the measure is part of the mitigation measures that were agreed with the authorities during the legal process.

“The water extracted from the well will be used to meet the drinking water needs of the population that makes use of the project (Mítikah), as well as the population that inhabits the area of influence of the well,” indicates the Declaration of Environmental Compliance prepared by the consultancy firm Plumarc.

Mítikah is not the only commercial project unknown about the concessions granted to it by Conagua.

In the REPDA locator, there are concessions that are under an owner that is not related according to the business activity or type of use of the concession. In some other cases, such as most shopping malls or mixed-use developments, the information is not available.

“It is urgent that the REPDA be verified. The information that builds it is only 10% of the wells that are being inspected for the actual flow, with the type of use for which it was requested,” explains Teresa Gutiérrez, general director of Agua.org.mx.

In order to avoid what has been called a clandestine market for water rights, organizations such as the National Water for All Coordinator are promoting initiatives for a new National Water Law that, among the various actions, makes it possible to provide complete information regarding concessions.

“The population needs to be informed about how much we have (of water), how much we can drink and what projects are being prioritized,” adds Carlos Vargas of the National Coordinator.

Entrance of the Mítikah Tower in Río Churubusco 601. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

Mitigate or stop

Less than 4 kilometers around Mítikah there are 10 other shopping centers: Galerías Insurgentes, Torre Macanar, Portal San Ángel, Plaza Inn, Pabellón Altavista, Plaza Loreto, Oasis Coyoacán, Patio Universidad and Del Valle City Shops.

In the midst of opacity, commercial projects continue to be built under the name of plaza, patio, park, oasis, and are also being converted into spaces for housing, hotels and offices.

In other cases, its structures are complicated, including entertainment venues such as the construction of the Parque Tepeyac shopping center, in the Gustavo a Madero mayor's office, announced with one of the largest aquariums in Latin America; or Las Antenas Park in Iztapalapa, which has an amusement park.

In addition to the repercussions on the water supply they bring, the increase in property, higher service costs, the demolition of trees, the privatization of public space and mobility problems have also been exposed.

However, the argument behind their growth is the commitment to economic development in the areas where they are established. For the Azteca Stadium Complex, the area is expected to generate 1,66 direct jobs for the construction phase and 2,720 during its operation phase.

“These are buildings that are very profitable and are likely to proliferate in central areas of the city, but they are for those who capture the productivity of those spaces, very small groups,” says Rosalba Loyde, an urban planner in Mexico City.

“Temporary jobs are generated that last as long as the project and that to maintain them, I would mean that we will have to be building permanently in the city... It means that we are talking about development at the macro level, because if we see it at street level, the benefits are reduced, especially for the original inhabitants,” adds Loyde.

Entrance to the Azteca Stadium. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

As part of the mitigation measures to mitigate the impacts of water demand, Mítikah and the Azteca Stadium Complex include the reinforcement of piping systems.

What for some water infrastructure consultants is a benefit because, just as there is a shortage of water, there is also a lack of investment that generates frequent leaks.

The Azteca Stadium also includes water savers and collection systems. While Funo, developer of Mítikah, said that 370 million pesos would be invested in mitigation and infrastructure improvement works around the project.

But for René Rivas to see the concrete park that the town of Xoco became and for Natalia Lara to live with a scarce water supply, there is no measure to compensate for the alterations.

Comentarios (0)