It was October 2014. The Cazones River woke up painted in green, blue and lilac colors. The cause was a spill resulting from the rupture of an oil pipeline operated by Petrleos Mexicanos (Pemex). The pollution reached Poza Rica, an oil city in the north of Veracruz, and its neighboring municipalities Coatzintla, Tihuatlán and Cazones.

The intensity of the smell of fuel caused headaches, vomiting and dizziness in residents of Coatzintla, where the accident originated. Municipal Civil Protection had to evacuate around 150 people to a social center while the authorities were making the tours to assess the damage.

Six months later, in 2015, the Security, Energy and Environment Agency (ASEA) would start operating. The emergence was part of the energy reform of then-president Enrique Peña Nieto (2012 - 2018). Its purpose: to monitor the industrial safety of the hydrocarbon sector to ensure environmental protection. A task that until then had been carried out by the Federal Attorney's Office for Environmental Protection (Profepa).

In the midst of debates about the future of the energy industry and the arrival of a new institution, the spill occurred in the Cazones River. But the story was nothing new, as it had happened before and continued to happen in the following years.

The problem with historic oil and gas extraction in southeastern Mexican states such as Veracruz, Tabasco and Campeche, is that the leaks and spills generated by the hydrocarbon industry have occurred by the thousands. Meanwhile, mechanisms for their regulation, such as the sanctions imposed by ASEA and Profepa, can scarcely be counted in the last decade.

Those who live in the countryside

“It is surprising to see the level of pollution in which the inhabitants live and that for them it has gradually become normal,” says Alejandra Jiménez, a member of the Regional Coordinator for Solidarity Action in Defense of the Huasteca-Totonacapan Territory (CORASON), a network of groups and communities that emerged in 2015.

Huasteca and Totonaca are two regions located north of Veracruz whose boundaries reach neighboring states such as Puebla and San Luis Potosí. In its landscape there are tropical forests, wetlands, lagoons and rivers. Corn, coffee, tobacco and sugar cane are harvested. In municipalities such as Papantla, the planting of vanilla stands out, an endemic species cultivated since pre-Hispanic times.

Currently there are the indigenous communities of Nahuas, Otomis, Tepehuas and Huastecos. The latter call themselves teenek, which means “those who live in the countryside with their language, blood and share the idea”.

Alejandra promoted CORASON in this region to monitor fracking extraction, also called hydraulic fracturing, a type of technique for obtaining oil and gas. The monitoring was extended to other environmental disasters that had already been there for some time.

Huasteca-Totonacapan has been an oil zone since before the Mexican Revolution. In the state of Veracruz, the first oil mantles were discovered in 1898, during the construction of the Tehuantepec railroad. In addition, the border with the Gulf of Mexico, where deposits have also been exploited, allowed the development of the industry and modified the dynamics of the region. There are cities that based their economy on hydrocarbons.

“It's very clear with the municipality of Poza Rica. Its history is totally linked to oil. This suddenly makes people naturalized to extraction, to problems,” says Alejandra Jiménez.

The reports received by CORASON about these accidents do not cease: a gas line explosion at the end of January, a gas pipeline leak at the beginning of the year, several more since December.

“We are talking about the fact that in this region there have been impacts by the industry since (before) the 1940s and that over time they generated a cumulative amount of damage. We haven't seen a clear response, not only from Pemex, but from the different bodies responsible for dealing with the issue of the human right to a healthy environment,” Alejandra points out.

Spills and escapes without sanctions

Around the world, the oil industry has reports for impacts on the environment and health. One of the most documented areas is emissions to the atmosphere. In 2020, a group of researchers published in the science journal Nature that the gases emitted by fossil fuels are between 25 and 40 percent greater than previously estimated. This represents a greater contribution to global warming.

In Mexico, in accordance with the Hydrocarbons Act, ASEA, as a decentralized body of the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources, has the power to issue regulations and regulations on industrial safety, prioritizing environmental protection.

In the event of any impact, in the Act of the National Agency for Industrial Safety and Environmental Protection of the Hydrocarbons Sector, which governs ASEA, it is specified that this body may financially sanction those regulated for any damage to the environment. As well as suspending or revoking licenses, authorizations, permissions and registrations.

However, this has not prevented Veracruz and Tabasco from concentrating 60% of spills and leaks in recent years, according to official figures provided via a request for transparency that go from 2018 to 2022. While on a national scale, from 2015 to 2022, Pemex has reported a total of 5,999 events in its sustainability reports.

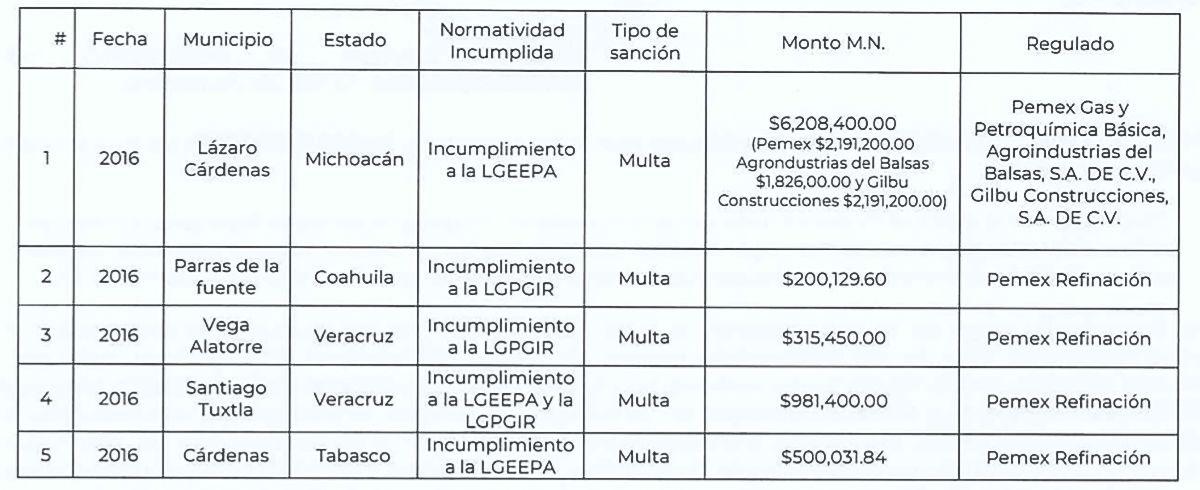

ASEA has only a record of having carried out 14 sanctions between 2015 and 2018, according to requests for information made for this report. This would mean that during the last five years of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, no economic sanction has been issued linked to spills and escapes.

For its part, Profepa provided a record of 636 sanctions over a period from 2010 to February 2015, the last month of its function before the Agency began its work.

For this publication, Pemex and ASEA were contacted to find out their positions on the matter, but at press time there was no response.

Confidential information

“Between 2015 and 2016, there was better research conducted by ASEA, but probably many specialists could agree that there is no convincing way to say that ASEA is doing a better job than Profepa when it comes to supervising Pemex,” says David Rosales, Managing Partner of the consulting firm Elevation Ideas and formerly a worker at agencies such as Pemex and the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE).

Regarding the 14 sanctions reported by ASEA from its various surveillance directorates, 9 are declared as “confidential information” for five years in accordance with resolutions 157/2022 and 457/2023. Therefore, only the name of the file was provided, but not the details such as the place affected, type of sanction or instance of Pemex involved.

For their part, the other 5 records that were broken down were for fines ranging from 200,000 pesos to 6 million Mexican pesos (between 11,700 and 350,000 USD). Of which, four are from Pemex Exploration, which, as its name suggests, is the body responsible for exploration, well development and hydrocarbon production activities.

Energy experts interviewed for this report agree that Pemex tends to reserve information and that there are not enough elements to understand why. Although in the last six years, companies such as Petrleos Mexicanos and federal government megaprojects such as the Maya Train have reserved information on the grounds of “national security”. The objective, according to authorities, is to protect the interests of the nation on issues that are considered to pose risks.

“Petroleos Mexicanos itself has had a series of internal structures for many years to identify and make public environmental changes or issues, but we have not yet had a sufficiently transparent mechanism to manage it, and that is why requests for transparency are often unsuccessful,” explained specialist Rosales.

In addition to this, it is difficult to understand what criteria ASEA considers to sanction companies in the field of hydrocarbons. In a review of regulations and laws in this area, article 26 of the Agency Act indicates that for the imposition of sanctions, the seriousness of the offence will be taken into account, mainly considering criteria such as damage that would have occurred to property or to human health, or the impact on the environment and natural resources.

The breakdown is joined by other variants that will determine the sanction, such as the economic conditions of the offender; recidivism, if any; the intentional or negligent nature; and the benefit directly obtained by the offender for acts related to the imposition of sanctions.

“The criteria are totally discretionary,” says Miriam Grunstein, a non-associate academic from Central Mexico at the James Baker Institute at Rice University. Adding that for Pemex it is better to save the penalty because the financing it uses and with which it could pay off its debt is public money.

Rosales agrees that public money is a factor and it commonly occurs in other countries with similar institutions. “It's not just a matter of the Mexican case... All countries suffer when it comes to wanting to regulate their public companies because they don't want to see one exchange and see the other. In other words, you know that any fine you are going to impose on your public companies also ends up being paid by the same country. That's why regulators must be independent so that there is no such political pressure when making decisions,” he says.

However, specialists disagree on whether or not there are preferences in the regulation that Pemex is having. Although it is a fact that the company has been backed by President López Obrador in promoting projects such as the Dos Bocas refinery in Tabasco. This has also sparked debates about what the federal budget is going to be.

“It's not that Pemex wants to reduce emissions or not, it's not that it's the bad guy in the story, but they just don't give it the budget to obtain the necessary technology to minimize its emissions,” Grunstein says.

Budget and pollution

To the north of Huasteca Veracruzana, from the waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the Pánuco River flows. Tilapia, carp, acaya and bass are some of its fishing species that have served as economic sustenance for communities in the region.

In addition, Pánuco water benefits several entities such as San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, State of Mexico and Tamaulipas. However, its proximity to the Francisco I. Madero refinery, as well as the infrastructure operated by Pemex in nearby municipalities, has this region under constant hydrocarbon incidents.

Academics from the Universidad Veracruzana (UV) have pointed out that all rivers that cross the state have pollutants from a variety of industries such as petrochemicals, agrochemicals, fertilizers, textiles, sugar mills and pharmaceuticals.

In the case of the Tuxpan and Coatzacoalcos rivers, oil activity is the main one due to leaks and spills that are attributed to problems with infrastructure. This is not counting those that occur due to acts of fuel theft, commonly known as huachicol.

“There are regions where there are facilities that are around 60 or 70 years old, some of them are still operating without sufficient maintenance,” Jiménez explains.

During the interview, the member of CORASON breaks down examples of effects on municipalities and their localities: contaminated soils in Papantla, damaged wells and streams in El Remolino and Emiliano Zapata, repeated leaks in Poza Rica, air pollution in Coatzintla. And that's just counting the north of Veracruz.

“There are leaks that Pemex personnel simply go to pick up the waste, but they already do it as a routine practice, not as an incident,” Jiménez says.

In the Federal Expenditure Budget (PEF) allocated for 2024, Pemex received just over 481,464 million pesos (28,207 million USD) for this year. However, only 4.8% of the total is allocated to infrastructure maintenance, while economic infrastructure projects - which include the exploitation of wells, the construction of platforms and work in productive fields - receive 51.6%.

“There is a directly proportional relationship between oil spills and lack of maintenance,” Grunstein adds.

For its part, the ASEA budget has also fallen. Since it began operations and until the end of Peña Nieto's six-year term, from 2016 to 2018, it had a total of more than 1,628 million pesos (more than 95 million USD). While proportionately during the last three years of López Obrador's six-year term, 2021 to 2024, a total of just 1,001 million (more than 58 million USD) was allocated to him.

Against a Giant

“The perception is that Pemex is untouchable... because from the outset there is a cultural imaginary in Mexico that we owe more (to the company) than it's going to give us,” Jiménez says.

According to the Pemex Sustainability Reports, the State company's contributions to communities are usually the delivery of new school furniture

to educational establishments of different levels or sports fields; the construction of community canteens; general and free medical consultations in Mobile Units; as well as the paving of some roads.

Measures that are beginning to be insufficient in addition to the demands of fishermen due to the pollution of the Pánuco River or farmers with affected fields in Papantla.

“A pending issue is pollution because it has not been possible to obtain research in this regard, but we do observe that there is a significant incidence of cancer cases, skin diseases, diseases such as asthma and other respiratory diseases that we could be associated with hydrocarbon activities,” Jiménez explains.

As part of the possible solutions, the member of CORASON insists that it is necessary for laws to be complied with and that different government bodies, such as the Ministry of the Environment and ASEA, “generate programs that can truly address the issue of repairing damages, as well as generating policies of non-repetition.”

For his part, Rosales raises the need for transparency and accountability on the part of companies linked to the petrochemical industry. In the case of Pemex, use part of the budget to improve the management of existing projects and settle debts.

“I don't think it depends on which party wins in the next presidential elections. I think it's important to provide ASEA with teeth, as they say in the jargon of regulatory studies, and to give it its own sanction elements that work, that make it increasingly appropriate. Because the company is failing to meet its objectives and more and more problems are occurring,” he said.

This text was produced with the support of Climate Tracker Latin America.

Comentarios (0)