From the Sierra Tarahumara, in northern Mexico, to Chubut, in Argentinian Patagonia, women from all communities have been coming together for more than a decade to protect the earth from one of the most intrusive activities in Latin America: mining.

One of them is Francisca Zamora, 59, originally from the town of Santa María Zotoltepec, in the municipality of Ixtacamaxtitlán, in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, in central Mexico. For 12 years, Francis, as he is known in his town, has been involved in the defense against projects of the Canadian company Almaden Minerals and the Mexican company Minera Frisco of businessman Carlos Slim.

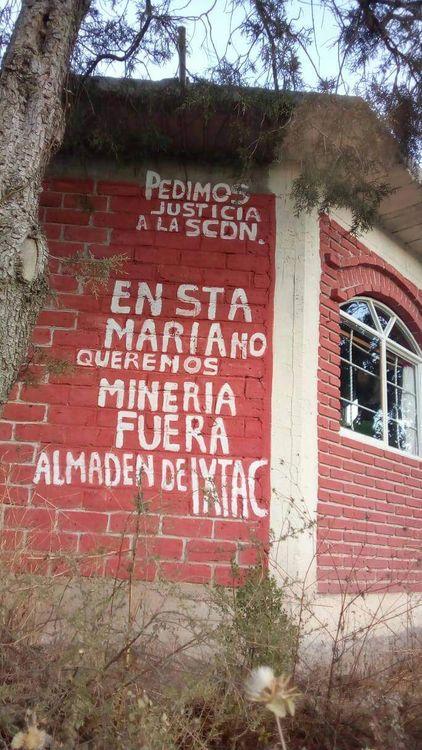

In Puebla, the municipalities of Ixtacamaxtitlán and Tetela de Ocampo have been the center of mining exploration activities for the extraction of gold and silver. “My house is more or less 300 meters from the (mining) properties where they intended to make the crater,” says the defender.

However, Francisca has spent a lot of time not only dealing with open-pit mines, but also with her community and her own family, who refused to recognize that mining could do any harm. So at the beginning, when Francis found out that in the neighboring municipality of Tetela they were organizing against companies, he began his fight from his community with a friend. And for several years it was just the two of them.

“I felt rejected by people and even by my own family. It was a very difficult thing because I thought they would be interested. I know all the people, I get along very well with the town and I was sure that everyone would see the mining issue, but the opposite happened and that affected me a lot,” says the defender during the interview.

Francis remembers the comments he received about it. They told her not to get involved; that she didn't have to walk alone so night after the meetings; that she should stay home because she was a woman. Although what she enjoys most is her time alone and her life plan has never been to become a mother or wife. “I like to live my freedom,” he says.

Painted in Santa María Zotoltepec. Photo: Francisca Zamora.

In addition to the rejection of the community, Francis also had to face mining companies, from whom he has seen intimidation and intimidation. She even once received a complaint from the Public Prosecutor's Office against her and other colleagues from the municipalities of the Sierra Norte de Puebla.

In Mexico, as in the rest of Latin America, the mining sector is one of the most violent for land and environmental defenders.

According to a Global Witness report, in 2021, 200 murders of land defenders were committed around the world. That's almost an average of four homicides per week. Mexico ranked first with 54, followed by Colombia with 33 and Brazil with 26. Mostly, due to conflicts linked to the mining sector.

In Latin America, around one out of every 10 defenders killed were women, of whom almost two-thirds were indigenous. In Mexico, women defenders are more exposed to violence such as threats, harassment, harassment and stigmatization.

“Due to the growing demand for food, fuel and basic products, the last decade has seen an increase in land grabbing for industries such as mining, logging, agro-industry and infrastructure projects, where local communities are rarely consulted or compensated,” explains the Global Witness report.

In the Sierra Tarahumara, in northern Mexico, the fight of Raramurian communities against illegal logging and mining has led to the murder of at least 8 land defenders and the displacement of dozens of families, mainly in Coloradas de la Virgen, in the state of Chihuahua.

“Women have been a very important pillar in the struggle of these communities. They have been active in legal-related work, they are the ones who go to the authorities to make the demands,” explains Judith González, a member of the Sierra Madre Alliance A.C., an organization responsible for accompanying peoples, both in their environmental defense and in other issues related to access to human rights.

Judith points out that unlike other spaces, Raramurian women have not been unable to take place as leaders, decision makers and creators of their own spaces.

They have opposed politicians and chiefs, who are the main agents of aggression in the area along with organized crime. The history of their participation dates back to 2003, when women and men from the community decided to stop illegal logging trucks.

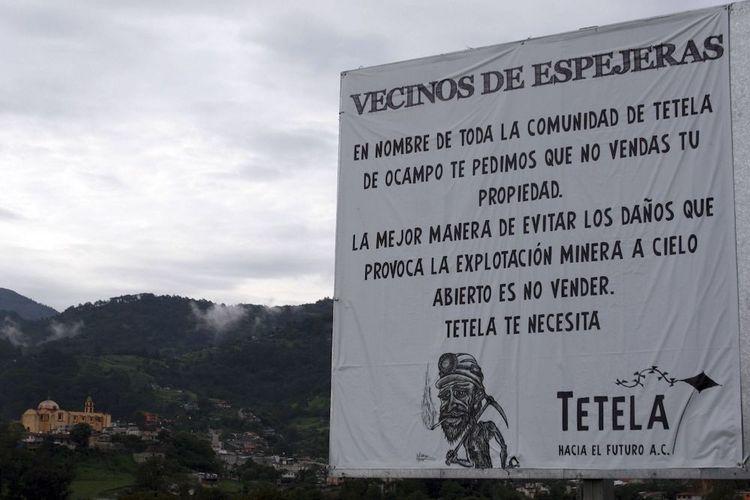

Announcement outside Tetela de Ocampo where Minera Frisco intended to operate. Photo: Hilada Rios/Cuartoscuro.com

“I think women are decision-makers when we set our minds to it,” Francisca says when asked how to deal with mining projects in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, where the main threat is Canada's Almaden Minerals and Minera Gorrión in Ixtacamaxtitlán.

Despite adversity, Francis is no longer alone. More than 10 years of struggle have generated greater organization and alliances between localities. There is even a group of 25 women who meet, talk, help at events and even lead a traditional medicine project.

They have also made significant achievements. Recently, the Ministry of Economy declared that it was not feasible to grant concessions to Almaden Minerals after a ruling in favor of the communities of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN) last year.

Currently, the main request of the peoples is to modify the Mining Law, which in Mexico allows 50-year concessions and places mining as a priority activity. “We have to combat the root problem,” says Francisca.

Regarding her role as a woman defender, she adds that she continues to face the machismo that persists in her community. “Let us know how to value ourselves and not be intimidated by men when we know that we can make important decisions in favor of life.”

Comentarios (0)