“And the extractivists tremble and tremble,” chants a group of people in a reduced march that crosses the central esplanade of Ciudad Universitaria, south of Mexico City. The white canvas with black letters that heads the demonstration reads: “From this faculty, those who build the megaprojects that displace us graduate”. The destination is the Faculty of Architecture of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

The march is symbolic and is part of the Meeting of Peoples and Colonies for the Defense of the Territory that was organized that same morning at the university facilities.

“Water yes, megaprojects no,” the chorus continues. Among those present are residents of the town of Xoco, of the Coyoacán mayor's office, who for more than 10 years had legal and social mobilizations against the Mítikah tower; there are also the inhabitants of the Magdalena Contreras mayor's office who defend the forests in the southwest of the city; and people from the town of Santa Úrsula Coapa, on the borders of the Coyoacán and Tlalpan mayors, who currently face water supply problems under the threat of real estate and commercial projects.

It is the town of Santa Úrsula Coapa that, for the past two years, has faced the construction of the Azteca Stadium Complex, owned by the company Grupo Televisa. A project announced as an extension of the football stadium that contemplated the construction of a four-level shopping mall, a seven-story hotel and a parking lot on the sidewalk and basement.

The purpose was to begin construction in 2024 and finish before the 2026 World Cup, which will be held in Mexico, the United States and Canada. But a series of mobilizations and meetings with authorities led this year Martí Batres, head of Government of Mexico City, to announce that the remodeling will only take place inside the Azteca Stadium, discarding the initial megaproject.

However, concerns continue in the town of Santa Úrsula over the granting of a water concession under the name of Televisa S.A. de C.V. of 450,000 cubic meters (equivalent to 450 million liters) per year in a region where the supply comes by tanking (schedules).

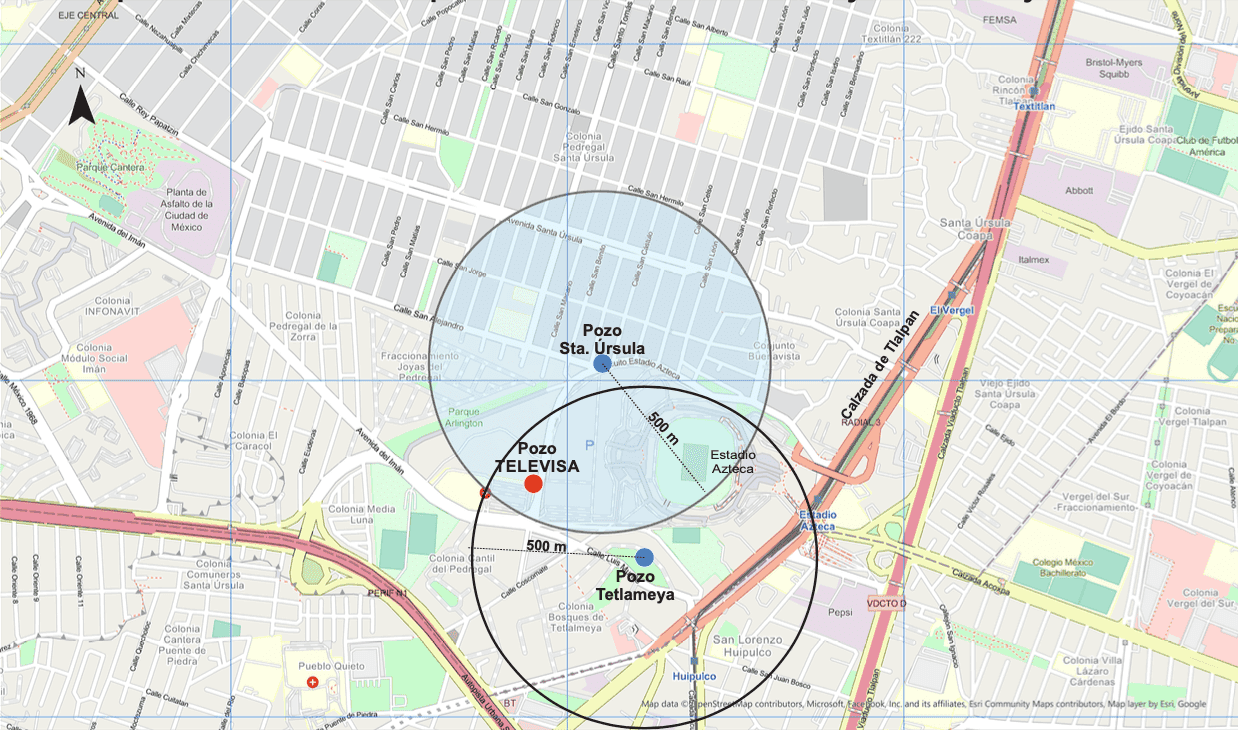

In addition to this, in the last two years, a water well was built on building number 42 of the Azteca Stadium Circuit. This was carried out without consultation with the people and ignored the fact that since 1952 there has been a ban to prevent the drilling of wells in the country's capital because extraction generates subsidence.

Although some capital authorities have said that the well will also supply residents, the town of Santa Úrsula Coapa asks for its cancellation.

March of the Meeting of Peoples and Colonies for the Defense of the Territory of Mexico City in Ciudad Universitaria. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

Youth at the Meeting of Peoples and Colonies for the Defense of the Territory of Mexico City. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

Concession, Well and Veda

On the march to the Faculty of Architecture, among the people holding the canvas, is Natalia Lara, a young woman in her thirties from the town of Santa Úrsula Coapa who for the last few years has been one of the spokespersons of the movement.

“We don't want extractivism to continue, especially in an area where there are already wells. We are looking at the possibility of introducing a legal strategy. We know that this well (in the Azteca Stadium) is violating some restrictions,” Lara says in an interview for this report.

Since 2022, the town of Santa Úrsula asked for information on the water concession and the construction of the well. However, the answer came only in early May from the Water Basin of the Valley of Mexico (OCAVM) through a letter explaining that the concession was granted by an “agreement for the transfer of temporary rights and total volume of water” between the private and the capital government through the Mexico City Water System (Sacmex).

This means that the Azteca Stadium well will also supply residents as part of an anti-drought program, despite the fact that there are already other wells in the surrounding area.

In addition, OCAVM points out in the letter that it will not be possible to stop the well since “the revocation of this concession, at this time when there is a major hydrometeorological crisis, would cause a greater impact on the neighbors who are being supplied with the water resource”.

“We wanted to mobilize earlier because the well hadn't been drilled yet and we think they hadn't answered us in two years because they gave themselves the time to build so that when we could do something, the drilling would already be there. These are some strategic tricks that we see being implemented and for us it is very important to make it visible that these types of concessions are being given to private companies when we are in a water crisis,” says Natalia.

Before receiving the official response, just on April 12, some residents of Santa Úrsula met with Sacmex personnel for a tour in which only Rubén Ramírez Almazán, the town's traditional authority, was allowed to enter for a few minutes to verify the existence of the well in building number 42 of the Azteca Stadium.

During the meeting, the neighbors shared their doubts about the amount of water that would be sent to the town, but the representatives of Sacmex only answered that the National Water Commission (Conagua) was responsible for authorizing and concession, while the governments of each mayor's office are responsible for the distribution. And they proposed scheduling another meeting where these authorities are also present.

“One of the actions taken by the city government was with private individuals so that they could have water,” says Alejandro Martínez, Sacmex Social Group Care worker at the end of the tour.

Location of the Azteca Stadium well. Source: Residents of Los Pedregales de Coyoacán.

Azteca Stadium well facilities. Photo: Patricia Ramírez

In 1952, the Official Gazette of the Federation published an indefinite ban on the lighting of groundwater, which is how extraction is known, in the Basin and Valley of Mexico, due to high demand, according to the inhabitants.

“There, it was determined that new wells could no longer be drilled and it was one of the causes that led to thinking about the creation of the Cutzamala System... a reason to look for external sources,” explains lawyer Alejandro Velázquez in an interview with Causa Natura Media.

One of the problems with this extraction is that it causes subsidence in the soil of the country's capital. Although it is also related to other impacts such as fractures, floods and tremors due to the rearrangements suffered by the layers of the subsoil.

Among the various studies that have been carried out in Mexico and other countries on the effects of groundwater extraction, the one published in the journal Science stands out, in which more than 20 researchers from the International Land Subsidence Initiative (LASII), found that it has become a global threat affecting 19% of the world's population.

In addition to the ban on well drilling, says lawyer Velázquez, in the most recent Update on the Average Annual Water Availability in the Aquifer of the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City, prepared by Conagua, it is reported that there is currently no volume available to grant new concessions due to a deficit of 480,000 cubic meters. Although this did not prevent Televisa from receiving the Azteca Stadium concession.

“All they (the authorities) do is transfer the name of a well that is exhausted to a new one and with this they say that they are not drilling, but they are transferring one that has already run out. For example, in the case of the Azteca Stadium, the well is a concession that was granted in Huixquilucan and those rights were transferred for the exploitation of the well in the Azteca Stadium,” Velázquez describes.

In Mexico, Conagua allows the transfer of rights derived from concessions for the exploitation, use or exploitation of water. This has been criticized by some specialists in water issues.

In addition, even if the Azteca Stadium Joint megaproject is not carried out as planned, the construction of water infrastructure would have to require the consultation of the original towns and neighborhoods, as recognized by the Constitution of Mexico City, as well as in international treaties such as Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization.

Meeting of residents of Santa Úrsula for the tour with Sacmex. Photo: Patricia Ramírez

Manta of the Town of Santa Úrsula Coapa in Ciudad Universitaria. Photo: Patricia Ramírez.

A Promise Called Progress

During the Meeting of Peoples and Colonies for the Defense of the Territory, interested students come up and a few more just out of curiosity. They listen to the problems, exchange comments, and when the time comes to meet at the tables that are planned as part of a workshop, all concerns arise.

There are stories about water shortages in the south of the city; others about pollution in the center of the capital; there are also mentions of rivers and forests that are lost to human activity; there is no shortage of proposals and ideas for projects.

According to the people of the villages and colonies, this is the idea of encounters: to form community and to act together even with those who are not being directly affected.

“The less people know, the more illegal procedures (the authorities) can do. What follows is to make lines of communication with the peoples of the citizens so that they are aware of what is happening,” says Rubén Ramírez Almazán, traditional authority of the town of Santa Úrsula.

One of the main arguments for betting on megaprojects is economic development. Natalia Lara believes that the benefit remains with a few. “We see that there is a significant flow of money and there is a big economic spill, but it stays with big businessmen,” he adds.

Specialists in urban development and economics such as Fernando Barona, an academic at the UNAM, agree that the economic spill is a myth; in addition to identifying other effects such as the change in social dynamics, the increase in property, the displacement of original inhabitants, among others.

“The important thing and what has always been said is the local management of the territory. In terms of water, in terms of urban services, they (towns and neighborhoods) are really the ones who suffer from the problem, those who live it and those who often have the solution to the problem”, adds Barona.

For now, the town of Santa Úrsula Coapa sees a solution that can cancel the concession for the well. But the biggest bet will be to achieve egalitarian development in which economic interests are no greater than the population's access to water.

Comentarios (0)