The ocean folds vertically, the water jumps over the slope riding its own shape, that violent caress is thrown towards the coast, sometimes, a simultaneous fold creeps the first one from behind, a third one may chase her dress. Almost always, the sound is an angry burst. There, human skin feels the blow and its expulsion, there, our species invented an elegant way to face marine exile: surfing. In 1997, the nature of the sea was challenged like this in 72 countries, and by 2020 the same was happening in 201 nations.

In this boat, surfers seek to escape unscathed, but not indifferent to the danger, to the immensity. By being very attentive to the movement of the ocean, by making an effort to understand it in order to experience it, to see up close what gives them movement and expression, it is that the community of surfers around the world notices that what happens on the coast can erase or —at least— anesthetize, the fierce song of the sea.

On the Mexican Pacific coast, that worries. Puerto Escondido extends over two Oaxacan municipalities, some beaches are in San Pedro Mixtepec and others in Santa María Colotepec, both demarcations have been competing for 1,300 hectares for 30 years. To the south of Puerto Escondido is Zicatela, a name that comes from Nahuatl and means “place of big thorns”, where the wave is full of ramps and can climb seven meters without ruffling. In November, the final of a competition brought dozens of people to the arena.

Women surfers are a pillar of activism in the conservation of ecosystems in Puerto Escondido. Photo: Lalo Romero.

It's just dawn and surfers measure themselves on waves of just over two meters. They seek to run over tons of water and cross a terrible tube created by the shape of the seabed; if nature suddenly fails to achieve such a feat, surfers take comfort at the edge of waves that spew foam. Competitions are possible here because the waves are constant, Zicatela's wave mane emerges like a storm off the coast of Chile three thousand miles away and accumulates for 36 hours while walking towards the coast of Oaxaca, where with the qualities of the shore, including the atmosphere, perfection is achieved. Great surf spots are rare, which is why such a space, in which eternal right and left waves break, attracts surfers from all over the world, here they are the majority of visitors and since 1960 they have returned this Oaxacan coast to tourism.

In 1980, when Sonia F. Moliner arrived in Puerto Escondido, she understood at a glance that the place “deserved everything: the name and the magic”. He found out about its existence from the photos in a magazine about hidden places. Her first trip from Mexico City was challenging, spending eight hours by train and then boarding a guajolotero for another 10 hours. In contrast, a flight from the center of the country to Puerto's international airport lasts an hour and 15 minutes, a matter that Sonia believes makes it easier for many young people to reach port fleeing their realities elsewhere. By the way, an airport whose expansion has been planned given the increase in demand. Before, he tells me, there was no high-end tourism, no amenities. The coast was lonely, dusty and austere for a long time, she fell in love with the fact that it changed very little over the years, that it was not Cancun, Cozumel or its neighbor Huatulco, the latter altered between social and environmental problems with the plans of the National Fund for the Promotion of Tourism (Fonatur) designed to give access to many people regardless of the vulnerability of the ecosystems.

In the image, some bathers in Zicatela. Photo: Arturo Pérez Alfonso/ Cuartoscura.

The citizens of Puerto Escondido see that attracting crowds is a bad plan encouraged by the Oaxaca-Puerto Escondido highway that can worsen two current situations: an unmet demand for water use in 40 percent of its population and wastewater pollution where 60 percent of the population has no drainage.

Despite the name, the place was never a big fishing port, “it was for shipping the coffee that came from the mountains,” Sonia explains from a place that she considers to be the last hidden place here, where they serve pickled fish that make you want to show off, but that Sonia asks us to hide at a time when everything is consumed soon. What can be said is that from this place they see the sea and a stone dock, made “because they wanted to make Puerto a tourist development for large ships, cruise ships and individuals”.

And suddenly a breakwater

That dock at Playa Marinero didn't keep its promises, which is certainly fortunate, but also everyone who knew this riverbank more than 30 years ago says that what it did was disfigure the coastline. Sonia tells me that before they all crossed some stones —now buried under the sand—to go from Marinero to Zicatela, one was a well-defined closed bay, and the other was an open sea. At that time, the sea current that came from the south crossed the bay, cleaned the place and left, but with the pier, which acted as a breakwater, the sea was removed and the beach grew. On the day of the competition, from the main avenue, —Del Morro— you can see a beach and the spectators' heads on the horizon before the waves: “The repercussions are brutal, surfers no longer have the waves they used to be”.

“They are called land earned from the sea, what a stupid name,” says Roxel, a surfer who believes that by naming them that we ignore what has been lost. She arrived in Puerto in 1992, when the streets were dirt, the mountains mostly and the sand had the black thorns that the Nahuatl name of the place still bears. Roxel has a tough voice and a frank smile, she took surfing seriously when she knew she belonged to the sea and as she says: “she felt the freedom to take waves without hindering anyone”; then, she dedicated more time to it and looked for her own equipment, something that was difficult before, when there was no tent after another every few meters like now, and she had to adjust to the available equipment that was for men, in fact, when training they were in the majority.

The Puerto Escondido surfing community has been threatened by the rampage of real estate development. Photo: Costa Unida.

On his constant trips to the sea, he saw the arrival of hotels and palapas, “the growth was gradual but continuous”. As other coasts were changed from beach bars to concrete structures, it is in the last seven years that that presumed virgin place changed. A lot. Local people accuse the rock breakwater of being an obstacle to the natural movement of currents and the cause of stagnant sand, they also point to the buildings that were built on Del Morro Avenue —which runs alongside the seash—of affecting the sandbank, such as businesses with imported names or the brutal construction that does not allow us to imagine an end date.

Roxel bodyboarding. Photo: Lalo Romero.

David is from Zicatela, his parents are also from Zicatela, and his grandparents are of Chatino and Zapotec origin. He is 25 years old and has been surfing since he was 10 years old; he, like Roxel, learned freely, escaped from school to go to the sea and learn from whom he will leave himself. At first he had no equipment, so he did what many local young people did: he borrowed. He is clear about it, “we neighborhood people have a harder time at first”. It was because David won third place in his first tournament that he gained equipment and inspiration to make surfing his life. His family did not encourage his visits to the sea, but his brother, who accompanied him, learned to fish to mitigate the scolding of going to the beach with a fish. Like the green-eyed surfer, David's specialty is bodyboarding, in which they ride lying on a cropped board. Marinero was also his school, he used to go with his friend Jafet, whom he considers to be one of the best in the board.

David knows that the pier took space away from the wave “it became very short, without space it becomes stronger, more dangerous for the surfer, now there are more accidents”. The risks in the waves, Sonia adds, are also due to the fact that there are now a lot of tourists “they are the same waves, but more and more people want to take them”.

The surfer community deduced that more buildings would leave them without perfect waves, “it's the best beachbreak (sandy bottom) in the world”, reveals David, he refers to that sand that is common on beaches, but which in the surfing world are described as extraordinary when the way it accumulates channels the waves when hit by a water cannon and “they improve both the size and the shape of the waves with pointed bowls in the right wave directions” explains David, and yes, Puerto Escondido is recommended by international surfers as one of the best. Its tube-shaped wave is known as the Mexican Pipeline, a name that equates it with the most photographed wave in the world, The Banzai Pipeline, a surf reef located on the north coast of Oahu, Hawaii, with a beautiful tubular shape, a delight for surfers.

Surfers are protesting against real estate damage that affects the ecosystems and the waves that have characterized the place. Photo: Costa Unida.

Because of its characteristics, Zicatela is a place for experts, on the other hand, those who take surfing as a fleeting experience frequently visit La Punta, the southernmost beach in Puerto Escondido; a place that before the pandemic was not the tourist space it is today and in which the community acts to stop the unsustainable development that is boiling.

Local and foreign bathers enjoy the beaches of Puerto Escondido, on Zicatela Beach. Photo: Arturo Pérez Alfonso/ Cuartoscuro.

La Punta

In the morning, the sunlight in La Punta spreads in a hurry. From a distance, the rocky area looks like the place that dozens of sea lions have chosen to rest, an animal like human bodies on boards waiting behind the waves, waiting for instructions or courage to ride their first wave. Many are taking their first surf lesson with local scorched skin instructors, others warm up their joints before tying a rented board to their ankle. In the sand, they test their paddling and the expected set-up, they evaluate how much they own their balance and listen to precautionary measures. David, like many surfers in Oaxaca, lives by teaching, especially to children, although here young people are the main consumers of the service.

Luz is from Edomex and arrived in Puerto Escondido when he was 12 years old, he sells surf lessons, he has never practiced it, but you only find out about that if you ask him directly, otherwise, it's hard to believe that he has no experience of what he narrates vividly. His four children ride waves; the youngest, Japheth, does it professionally. And so, without ever having ridden a wave but drenched in that world, Luz believes that nothing compares to “feeling the touch as if you were inside a cloud, the feeling that maybe you won't be able to get out of there, the roar of the tube inside you when you go inside, it's like spitting on you”.

Surfers from all over the world flock to the beaches of Oaxaca for their international status. Photo: Arturo Pérez.

She talks about the waves from other parts of the world and shares the information she has squeezed from the internet, occasionally interrupting her wave of curious facts to ask: “Are you going to rent a board?” , to every passing tourist. He sells classes, but his son, Janet, didn't pay to learn, he also did it out of the blue and supported by locals, with the challenges and accidents that entail; he stood out for his talent, and soon his mother noticed that for him it wasn't a hobby even though the needs at home were many and they used to complicate the surfer's career, such as having to sell the boards that sponsors and contests gave him to bring money home.

Classes such as employment, competitions and their economic incentives for local surfers, board rental, as well as the provision of food, lodging and entertainment for tourists are part of a socio-economic context that originated in the waves. What happens in this place is no different from other coasts valued by surfers. There are even surfonomics, studies that document the contribution of surfing to local economies and that, with luck, become data to encourage coastal protection.

One of the first studies focused on Mavericks, California, was commissioned by Save the Waves Coallition (STW) —a California-based non-profit organization that protects surf ecosystems—which found that surfers visit an average of five times as much and contribute around 24 million dollars a year. For the case of Puerto Escondido, Ralph Pace indicated in his study that the pristine state reported in 1960 by surfers does not exist after people arrived en masse and tourism grew without sustainable care. “While the wave is still considered world class, it is far from its original state. It's not clear how much more degradation can occur before surfers decide that it's not worth spending all the money to surf.”

Regarding Puerto Escondido, Ralph Pace noted that the degradation has put the future of the place in jeopardy as an attraction for surfers. Photo: Arturo Pérez Alfonso.

For his part, Alberto Valencia identified through interviews that residents perceive care for the environment on the part of surfers, who they attribute “to the close relationship they experience with the sea”. Their study also says that Global Industry Analysts Inc estimated that, by 2024, surfing will leave a global impact of more than 10.03 trillion dollars by improving boards, clothing and access to artificial parks and natural destinations.

But it's not just in relation to the wave that these places matter. When they are defined as surfing ecosystems, explains Mara Arroyo —who has been part of Save the Waves Coalition for eight years— she describes the environment of quality waves, a trait that is difficult to specify because it implies the perspective given by the surfer's experience and that “they are suitable for surfing, the frequency with which they break and that they offer the possibility of creating an economy or culture”, in addition to the physical characteristics that create ruptures, such as tidal waves, soil and seabed, history, ecology and defense are relevant communities linked to surfing ecosystems.

The extinction of waves has already been documented, “in Baja California north of Ensenada there was a wave where the gas station is now and it disappeared,” says the environmental doctor and adds that the waves can die or mutate, “it doesn't break in the same way, it doesn't break with the same frequency, it doesn't do it with the same intensity or it just disappears”; other cases are Killer Dana, Flood Control, Copacabana, Corona del Mar, Harry's, Ponta Delgada or Madeira, the latter being an island where it was warned that if a boardwalk were built, surfing would be more dangerous and that's how it happened, the wall was erected and the surfers stopped looking for the place.

For Roxel, her family's sea life is important, not only because of the economy, “what we do is thanks to this, our diet and our routines,” she says and assures that without the family habits that training gives, her daughters' activities could be different, “they could be looking for ways to get that energy elsewhere, going to the disco, going out to party, because Puerto gives it to you, people come here on vacation”, which results in a coming and going of strangers. He also shares that surfing gave others discipline and identity despite their problems, “I can think of a couple who didn't have a mom or dad, and that having been surfers or bodyguards gave them an identity, a reason to look for something good”.

Preserving waves is caring for ecosystems, local activists say. Photo: SOS Puerto.

A surf ecosystem is not just perfect waves, although everything is born in them; walking on the sea may be a fleeting act, but it requires a constant presence. On every face I see that the temper required to enter these parts of the ocean of a furious nature is the same as that experienced in the defense of the waves.

The degree of identity given by this phenomenon is visible in the multiple civil groups that protect the cleanliness of the seas, that access to beaches is free and that denounce coastal erosion, pollution, intensive sale of land and the uncontrolled construction of buildings, as well as poor management of wastewater and garbage. For Sonia, as for other people who love Puerto, it's not about holding back progress, “but we want it to be respectful, sustainable, ecological, inclusive and peaceful.” Sos Puerto Escondido, Salvemos Colorada, Costa Unida, Red Costa Viva, Conecta Puerto, Jungle Plastica, Vive Mar, Save Bacocho, Oaxacan Fund for the Conservation of Nature (FOCN) are some of the civil organizations that seek sustainable development on the Oaxacan coast.

Roxel lives in La Punta, she says that before the pandemic there were few buildings, that there had not been such a rapid increase in business as during the Covid-19 contingency and that, unlike the rest of the coast, La Punta was the most shameless case, that the sale of land was massive and new businesses sprouted like mushrooms. “Land everywhere is being sold, meaning 'come and live in Porto', that's the hidden message and not so hidden.” On the Oaxacan coast, during the pandemic, many content creators on social networks attracted tourism to Puerto, showing how paradise and paradise began to become more expensive not only for visitors but also for residents.

Faced with problems, the community of Puerto is making waves. For two years they have been watching for the development they want, “here it is governed by uses and customs, there began to be people who did not allow growth to continue like this, the Municipal Delegation and the community became participatory,” says Roxel, referring to the municipality of Santa María de Colotepec, which is governed by uses and customs, although the municipality of San Pedro Mixtepec does so through political parties, a contrast that complicates the regionalization of agreements.

They go with their eyes on their shoulders. “One, two, three... four. If that has already happened”, “there is a fourth floor up there”, “that one was going to put another one, you can see the rods”, this is how those who walk together communicate their indignation, suddenly they shout it so that the entire entourage can hear; on more than one occasion they stop to talk to the masons, they ask them if they are not going to lay another floor, or they remind them that this third, fourth or fifth is not going, they warn them, although they know that to stop them they will have to work from other fronts, but that morning they walk.

Buildings in Puerto Escondido are growing in line with tourist demand, with direct effects on the ecosystem. Photo: Dark room.

Melecio, an older man who goes with young Oaxacans and foreigners, says that before, the colony they watch over, Brisas de Zicatela, was pure mountain, Luz will say it was pure huizachera (sticks of thorns that burn easily) or “a land for which no one gave a damn”. He recalls that before the land was distributed, the place was cleaned up, that it all started with a dozen houses that multiplied slowly, steadily but without pause, although never with the speed they did during the pandemic. He points out that buildings can damage waves, but also block the view of the sea, both of which seem equally unfair to him.

Building surveillance takes them a couple of hours under the sun, and the participants are clear that the community does not want buildings that exceed nine meters. During 2022, Felipe was a delegate (a position granted by the community to a local representative who is a liaison with the municipal government) of Brisas de Zicatela at that time he participated in works for the colony and taking care that the assembly agreement approved in 2008 is implemented, which motivates young people to demand two floors and a palapa as a construction limit. “When they come to pay for their proof of non-debit, we make them sign that agreement and when we see that they don't want to respect it, then I bring people together and we're going to remind them.”

The community is organizing against multi-story buildings that are being built in the municipality. Photo: Taken from Twitter.

The subject of wind is not whimsical, but intuitive, this force changes the surface of the seas all the time. Oceanographer Gino Pasqualana explains that tall buildings block the morning offshore wind from the mountains that blows to the sea and softens the wave, “scientific studies have not yet been done to prove this, but based on local knowledge from years of surfers who live there, they have noticed that the construction of higher buildings blocks the offshore wind —the land breeze— and that this has an effect on sanding up the area affecting the wave”. José, treasurer of the delegation and surfer, explains that about 15 buildings have been arrested in the colony, some of them intended seven floors, and today several three-level buildings are pending. José says that this fresh air gives good wave seasons, and in summer, surfers wait for him in the morning and in the afternoon.

In the formation of waves, marine storms, sandbanks, climate, mountains, water quality and offshore, among other elements, create unique recipes in each area. In Puerto Escondido, good tides from March to October feed heavily on the swell, which are open ocean storms that move water from far away. In the case of Puerto, this energy comes from the southern hemisphere; the other months, the waves depend more on offshore wind. In Zicatela, in addition to the immense Mexican Pipeline, there are other wonders such as Carmelitas and Farbar, as well as the La Punta wave, each with different qualities and vulnerabilities to landscape change.

What stirs a wave

When the architect Miguel arrived in Brisas de Zicatela to do a work, he sought what he should: legal instruments to guide his work, “whether it be a development plan, zoning, land use, municipal or state regulations”, he found the “Construction Regulations of the State of Oaxaca” published in 1998.

He believes that this document does not consider the needs of the community because it is state and that because it was made 25 years ago it lost context. At the beginning of the project, he knew, by the regulations, that on roads less than 10 meters he could build the width of the street in height, but on roads larger than 10 meters they allowed one and a half meters per meter (on a road of 10, go up 15). This was guided by and included 40 percent of green area, wetlands with fluffy stem plants for wastewater treatment and a cross wind architecture so as not to impact the waves. The young architect was allowed to complete his project even though he passed nine meters, but, he admits that even without being spelled out in a development plan, today “I don't do more than two levels crazy, nor more than 9 meters, this has to be respected because that's what the community asks for”.

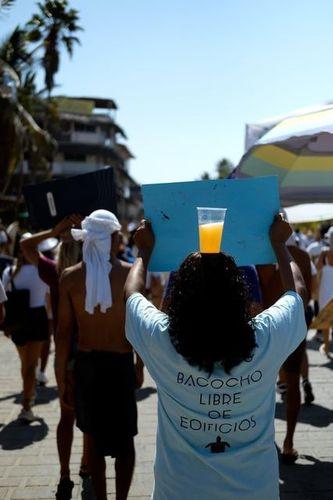

“Free of buildings” surfers demand at a protest. Photo: SOS Puerto.

Miguel's case shows what Sonia considers to be the basis of social demands in Puerto: dialogue. “The new governor of Oaxaca signed a letter of commitment to support urban tourism and infrastructure development in Puerto Escondido and we collaborated by presenting 32 points that seemed basic to us for him to draft an Urban Development and Construction regulation.”

In the field of science, Gino Passalacqua shares his version of a scarcity of documents: studies. He clarifies that the difficulty is to have a good database made with various instruments that measure currents, sediments and seasonal flows over a long time to understand qualities in different environmental conditions, including some global ones.

A more common option for understanding coastlines are reanalysis studies using satellite tools and data sources, which show wave frequency and height. But when evaluating the damage that humans do, Gino says that there are computer models of the ocean and the atmosphere that integrate the current wave conditions in which to simulate changes such as breakwaters, springs or modification in sediments and reproduce with computers what would happen.

Mara Arroyo, responsible for the Network of Protected Surf Areas for STW, highlights that to define protected areas, detailed studies are required, which take a long time and are also expensive; therefore, it is common that only one area is evaluated for a potential threat or when an Environmental Impact Manifestation (MIA) is required for some work, for example, for the expansion of the oil and industrial port in Punta Conejo, Oaxaca. The other challenge is to determine if the demonstrations are well done and honest.

With these studies, it also happens that they do not focus on wave protection, nor on the dynamics of surfing, nor on what the coast can change if they become extinct. In fact, the scientist explains to me, the usual thing is to talk about waves thinking about how it would affect our infrastructures. “In Baja California, a proposal was made to install pipes for taking and discharging seawater near the Tres Emes breakwater, but the topic in the study was not whether the wave was going to be destroyed or affected, rather the studies were to understand resistance and design which had to have the pipe structure to withstand storm surges”.

Surfers in Puerto Escondido. Photo: Wiliam Wallaz.

Changing the way we see the waves, from a dangerous event to a surfing ecosystem, environmental defense is born. “A main component of protecting coastal ecosystems is that there is the support and interest of local people, without that you can't move forward, no matter how much you want and see the obvious threats,” Passalacqua explains. It was from a local interest that the law of ruptures was achieved in Peru, which restricts infrastructure development, oil and gas exploration, and fishing that threatens high-quality surf spots. The law not only considers the beauty of surfing, but its economic and environmental contribution.

It took years to draft and approve this law, today they have 30 waves under legal protection in a country with historical vestiges of fishing boats capable of navigating waves, the totora horses, with a cultural roots as notorious as “the sport of the kings of Hawaii” called “Hee Nalu” or “wave gliding”, which is considered the worldwide origin of this sport.

With its law, Peru became the first country in the world with a legal system to protect these marine forms and consider them a legal asset with rights. Its Breakers Act was created in 2000 and 13 years later the regulation that puts it into action was approved. Today, to protect a wave, it must be registered in the register of breakers after making a technical file that indicates its peculiarities, with this, wave protection also involves diversity, including the ways of life that communities develop around them. One problem is that a report can cost up to 5 thousand euros (about 100 thousand pesos), which they try to pay with the Do It For Your Wave campaign. In Mexico, “there are tools and mechanisms, we just have to see how they can be adapted,” says Mara Arroyo, although she knows that it will be important to create management plans that recognize waves as a resource subject to protection.

In Peru, if a protected wave has been affected, whether it alters or eliminates it, the cause of the damage must “restore things to the state before the damage was generated”. Of that degree of challenge, will it be possible to recreate extinct waves?

In the absence of laws like this, in other countries STW has designated World Surf Reserves since 2009. The program is similar to those of Unesco; every year they open a call, communities apply for sites and an executive committee chooses one. This is an honorary degree, not a legal designation, but those who obtain recognition must create strategies to care for them. The committee considers “the quality and consistency of the waves within the breakwater zone; the environmental richness and fragility of the area; the wider relevance of the place to the culture and history of surfing, and the support of the local community”.

Mexico has the Todos Santos world surf reserve. Photo: Bahia Todos Santos World Surfing Reserve.

There are 11 world surf reserves in the world; Mexico has one in Baja California, which is Todos Santos Bay, which was also selected for “its great diversity of species that depend on the intertidal and coastal areas for their survival,” the designation document indicates. By the way, it is known that about 85 percent of the best surf spots are located in hot spots of high biodiversity. Two environmental problems of this Mexican reserve are the decline in water quality and the accumulation of waste. The place has five surf spots, two with indirect legal protection, namely the San Miguel breakwater, inside the state park; and Killer's, which is in the Pacific Islands Biosphere Reserve.

San Miguel is considered the birthplace of Mexican surfing. The park initiative was born 30 years ago, when the locals wanted a community space, where Pronatura Noroeste did studies and sought the protection designation, at that time it did not include surfing, then Bahía de Todos Santos became a world surf reserve in 2014 and Save the Waves supported the Arroyo San Miguel state park project, thus indirectly protecting the wave, “although the marine area is not part of the park, the wave depends on the contribution of sediment from the stream, on the dynamics of the stream,” Mara explains. Sites that don't have legal protection have a community fighting over issues of access and pollution.

Other defense strategies are born locally; for example, Roxel was part of the delegation in 2021, at that time he filmed his daughters as they were surfing the waves, and suddenly he recorded something else: accidents. These happened between boys and adults, between the one who rented the board and the one who took classes, so it seemed obvious to him that La punta was becoming dangerous. He showed the Cabildo a couple of accidents involving children to make it clear that younger people needed a safe space to learn like the Roxel generation did in Marinero. Today at the entrance to La Punta Beach, a sign shows the municipal agreement: “SATURDAY and SUNDAY ONLY KIDS UNDER 16 from 6am to 10am”.

“I had the opportunity to learn to surf on beaches where we were only children, in Marinero, I was only young, and if I wanted to go to the tip or to Carrizalillo, I was 16 or 17 years old, there were no farts, there were no classes, there was no tourism and I could learn; then, when I was older I managed to represent Oaxaca in national teams (...) but all because I could learn to surf on my beach”, he emphasizes and adds “if we want there to be more champions, then we have to open a space for them”. David believes that they should have all the children surfing there, “it's our wave, we need local surfers. We also need more tournaments, more events, more support.”

For Passalacqua, having a space for training took on another dimension since surfing debuted as an Olympic sport in Tokyo, “implies that the government of each country is obliged to contribute to federations so that it can be developed as an Olympic sport, but there is no interest on the part of governments to protect stadiums, which are the waves”. According to the International Surf Association, more than 35 million people practice this sport.

Surfers in Tenerife, Spain. Photo: Buiobuione.

Other waves

The oceans cover 70 percent of the planet, stories of pollution abound in all of them, and the Oaxacan coast is not exempt from them. During the rains, Roxel sees garbage falling from the ravines, more and more so every time. Early in the morning, on La Punta beach, an encounter with plastics is more likely than with black thorns. Pollution in all its versions fuels climate change, an issue that models waves.

On the one hand, it is known that global warming increases sea level, and it has also been identified that the greenhouse effect and its atmospheric conditions impact pressure and wind patterns, which, in turn, can affect waves. Climate change will also modify storms, it is known that if the direction or force of the waves is different, beaches and ports can be eroded, if the wave periods change, sedimentation would be different.

Along the coasts, water can take an unfortunate path when wastewater management falters, something you can already see, or rather smell, in Oaxaca. Ariana Eleuterio's master's research indicates that sanitary drainage coverage in the city of Puerto Escondido is 48 percent, so septic tanks proliferate that do not meet hygiene requirements, while for the eviction of water in the region there are four treatment plants, two with problems so that the water comes out as it is received and thus discharged into the sea; and one more, the one in Punta Colorada, overflows in the rainy season.

Sonia explains to me that Puerto is not ready to receive crowds, “there is no infrastructure for drinking water, nor for the recovery and treatment of wastewater, there is no electrical network that works properly without failures for the operation of reservoirs and plants”. These problems, he adds, are investigated “with the nose, because it smells like it stinks”. This was the case in the Zapata Cárcamo, where sewage fell in Zicatela near Tamarindos, a fact that “both the authorities, civil society and the community managed to fix it”.

The town receives mass tourism. Photo: Arturo Pérez Alfonso/ Cuartoscuro.

Associations estimate that only 30 percent of wastewater can be treated in Puerto Escondido. Faced with the arrival of more waste, Sonia wonders “how are we going to find Puerto after this wave?”

His doubt is due to the fact that not only those connected to the drain have deficiencies in their water cleaning, since septic tanks are emptied from time to time according to their capacity and use; pipes pump waste that leads to reservoirs; from these collection tanks it is sent to treatment plants, but these do not give way to the increase in population. So it has happened that the State Water Commission (CEA) hires pipes to prevent reservoirs from overflowing, but when it takes them to other reservoirs, the Zapata thing happens.

At night, while some people set up the tables they rented that day and others sell their last nighttime drinks, the lights of the palapas and the bars are coordinated with the blue lights of a pipe on the main avenue of La Punta, the vehicle spans the width of the street and brings the purr of its pumping to the place. The smell on the street also changes when the water is removed.

Sonia believes that to achieve changes, one must be defined so that others can have references. When she moved to this coast, she settled in a house built 22 years ago, canceled the septic tank, installed a biodigester for sewage and a biofilter with wetlands for gray water, she recovers that water to irrigate her garden, “she hasn't sent my shit to the sea for three years”. In his house he has fragrant herbs and mango, soursop and chicozapote trees.

Measures like these could have more impact if they leave spaces that occupy large volumes of water such as restaurants and hotels, so recently the SOS Puerto association invited owners of tourist developments to learn about biotechnology options for wastewater treatment such as biodigesters, ecological graves and artificial wetlands.

“Puerto Escondido is not hidden”

At other times, the community has come together to avoid harm. One of the achievements of SOS Puerto is an incentive for many associations, namely the cancellation of an 18-story hotel on Bacocho Beach, where 80 apartments were going to be built in the vicinity of a turtle camp. To stop it, they prevented the trucks from removing sand from the place, then they set up 24-hour guards with the solidarity of the community until the municipality of San Pedro Mixtepec stopped the work. There it became clear that Puerto “is no longer hiding, but that Puerto is going to demand that they respect,” Sonia points out.

Citizens of the port are protesting against large buildings. Photo: Jacqueline Santiago.

Accompanied by an Oaxacan music band in February of this year, the population held a parade after succeeding in suspending a concrete construction in front of Del Morro Avenue on the sand for a beach club in the federal area earlier that month with complaints to Profepa and after a 10-hour sit-in. Their arguments were that the construction did not have a study on how the movement of sand would affect the beach, flora and fauna of the place, the negative of the construction being thought of sand —something forbidden— and in the middle of a temporary stream, combined with the poor management of construction waste and the absence of a plan for managing solid waste, as well as gray and black water for the area.

In the peaceful demonstration organized by Costa Unida, the citizens' journey was festive, a declaration of principles in the defense of the waves and the search for progress with respect for the place; with banners, the population called for sustainable development, with infrastructure for wastewater, for the protection of the livelihoods of the community and the biodiversity of Puerto Escondido, but they also painted some surfboards with messages such as “take care of our future” and “clean water = decent life”.

After that, they sent Governor Salomón Jara Cruz a letter stating that Puerto Escondido is the third most important tourist destination in the state and that its attractiveness is mainly due to nature, but that there “accelerated growth continues to occur without the corresponding regulations (ecological and territorial)” and indicate that these are necessary to avoid negative impacts, just as an Urban Development Plan is required, which for the place must be conurban since territorially and politically it is two municipalities.

David talks about the concept of location thinking about how it defends itself and belongs to water and land, “even if I'm in the peak, being a foreigner in another place, the local one, the one from there, can catch the wave”, he explains, “that's how they handle surfing, that respect is worldwide, here, in Hawaii, in Chile, in Australia, in Portugal, everywhere the local rules”, he makes it clear: “There are people who grow up here or who spend time and call themselves local, but you're not local if you don't fight your land. Do you want your wave, do you want your picture here? , very crappy here, appearing in magazines and this, what's the use of it if you're not doing anything for your people?”

Thinking about local issues, Mara says that there is no reliable database on waves and surfing, “studies are generated in isolation and there is still no database that can help us to identify sites with potential for protection”, and explains that what does exist is an app, “people can participate in beach monitoring and contribute to the generation of a global wave database, the app is called Save the Waves and anyone can record problems and georeference them”.

The scientist believes that the wave is a vehicle to promote environmental initiatives and strategies, and also to finance protection projects. Roxel also believes that the sea inspires hope, that even if you have the worst surf session “it rolled over, you hurt yourself, you broke your board, but in the end, even if everything is bad, you could have been there (..) despite everything bad that could happen to you, you know that the next day you can return. There's always that connection. Because of that knowing that the next day I can return or that the next day I will return, is that I think we are doing something because there is still that hope”.

* This work was supported by the Marine Journalism Network (Repemar), promoted by Causa Natura with the help of the Earth Journalism Network of Internews.

Comentarios (0)