By César Hernández/Mirror Magazine

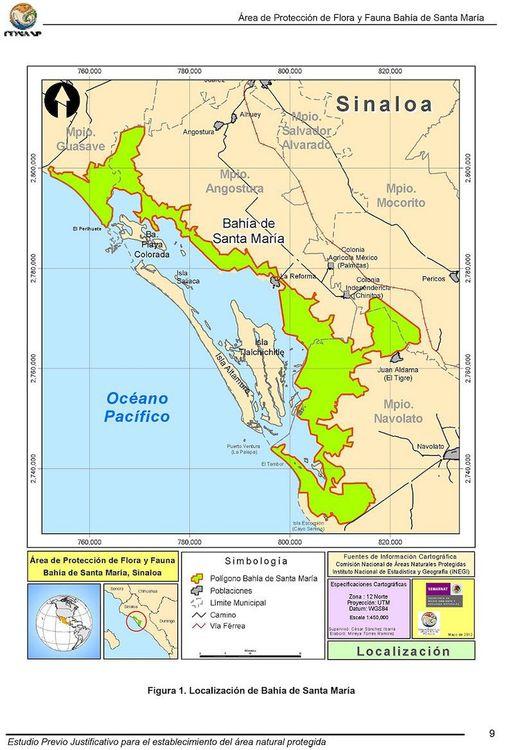

Santa María, Angostura, Sinaloa.- When the “Preliminary study supporting the establishment of the protected natural area: Santa María Bay flora and fauna protection area” was presented, it seemed that the State of Sinaloa was ready to protect 67,639 proposed hectares and that, like areas such as the Cacaxtla Plateau, there would be a new Protected Natural Area (ANP) to “make the most of the advantages offered by each of the various areas to optimize natural resources and in turn conserve them (...) with the main objective of maintaining an ecological balance between economic development and the coastal ecosystem”.

However, the project did not materialize.

The exact reason is not known, say environmentalists who were involved in the process. However, they add, the failure of this effort had to do with the mismanagement of the State Government at the time, as well as the strong pressure of an aquaculture sector eager for expansion.

The importance of the bay for the environment is supported by several appointments that over the years have emphasized the relevance of the area for ecological balance. This site is part of the hemispherical network of reserves for shorebirds (RHRAP/WHSRN) that is within the Gulf of California Islands Protection Area, is considered a priority wetland by CONABIO, is an MAB-UNESCO World Heritage Site, a Ramsar site and one of the few homes of goofy blue-legged ducks (Sula nebouxii), a species that was recently given relevance with a statue on the Malecón in the town of La Reforma, in the center of the bay.

Blue-legged fool on the Malecón de La Reforma, Angostura. Photo: Josué David Piña.

However, none of these appointments protects or establishes rules for the proper use and utilization of the area that ensures its sustainability over time.

Faced with this situation, organizations such as Pronatura Noroeste have resorted to a strategy that various actors describe as “a last resort” to protect the bay: the purchase of private land in order to use it for conservation. Thus, as of August 2023, the Area Voluntarily Intended for Conservation of the Santa María Bay Ecological Reserve totals 2,500 hectares that, although recognized by the Federal Government, are managed and maintained by private means; a challenge to which is added the lack of legal and administrative tools to protect it, and the ignorance of people who in one way or another take advantage of their wealth.

Aerial view of Santa María Bay from La Reforma, Angostura. Photo: Marcos Vizcarra.

The cast

“How can you explain that there are wetlands that are ejidos or that are beaches? It can't be!” , exclaims Dr. Diana Cecilia Escobedo Urías.

The specialist is part of the Department of Environment of the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Integral Regional Development (CIIDIR Sinaloa) and has 26 years of experience studying coastal eutrophication, the most important water pollution process in lakes, ponds, rivers, reservoirs, etc.

“These are the changes that exist in environmental quality due to the increase in nitrogen, phosphorus and all the consequences that occur in an ecosystem due to the increase of these on the coasts,” she explains.

“The federal government, cleverly, because there is no other way to say it, hands over a lot of federal land to the ejidatarios,” he continues.

“It's the same story of the federal zone where they want to put the ammonia plant (Topolobampo). It was ejidal, but it's a federal zone, how do you explain that the ejido had it? Then land use is alienated and handed over to a private individual (...) that was a perverse management of the land from the agrarian distribution”, he reviews.

This is documented by Modesto Aguilar Alvarado in his book “From the Páramo and the Saltpeter to the Irrigation Paradise in Colonia Agrícola México (Palmitas)”. This volume recalls how in June 1959 the general and governor of Sinaloa Gabriel Leyva Velázquez offered settlers from various states land from the Las Bocas estate, in the current municipality of Angostura, under pressure from the then governor of Michoacán and brother of former president Lázaro Cárdenas and, according to the book, to avoid distributing 'estates disguised with the small property' of the Culiacán Valley, which by then were already irrigated land.

It was those ejidatarios who, at the end of the 90's, the civil association Pronatura purchased their plots to integrate them as a Voluntary Conservation Area or ADVC.

Emerged from a reform of the General Law on Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection in 1996, the figure of ADVC's are a protection mechanism recognized by the Federal Government that is established by means of a certificate granted by Semarnat. Currently, the official CONANP website reports 545 nationally recognized ADVC's, a total of 718,283 hectares protected and managed by their owners in accordance with their own management strategies.

By 2012, Pronatura had purchased 766 hectares under this figure, and by 2023 the Bahía de Santa María ecological reserve totals 2,500 hectares of coastal ecosystems and critical habitat for shorebirds and migratory aquatic birds under the reserve.

“The only way to conserve an area is for someone to buy it,” says Escobedo Urías.

Guardians of the Bay

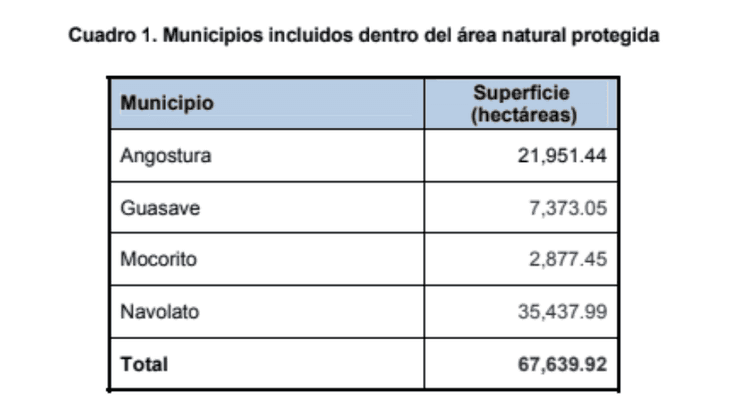

Located between the mouth of the Sinaloa River and Altata Bay, in the municipalities of Navolato and Angostura, Santa María Bay comprises, according to the previous study justifying its establishment as an ANP, a total of 67,639 hectares of the central-northwestern coastal areas of Sinaloa, in the municipalities of Angostura, Guasave, Mocorito and Navolato.

The area is mostly comprised of wetlands, coastal lagoons, islands, peninulas and bays. With an altitude ranging from 0 to 20 meters above sea level (meters above sea level), its agricultural use is limited by high salinity and the main activity is shrimp farming.

Regarding its flora and fauna, the bay “has aquatic and underwater vegetation in some small lagoons and streams, dune vegetation, mangroves on the edge of the coastline and completely covering some islands and islets and deciduous and tropical deciduous thorny forests in small patches”.

In these ecosystems, there are records of 477 vertebrate species distributed in 25 species of fish, 20 of amphibians, 66 of reptiles, 310 of birds and 56 of mammals. Of these, 74 are listed in some risk category within the Official Mexican Standard.

Currently, 2,500 of these 63,000 hectares belong to Pronatura, such as the ADVC Bahia de Santa María Ecological Reserve.

Juan Carlos Leyva, coordinator of Pronatura Noroeste. Photo: Josué David Piña.

“We are in the center of what is known as Santa María Bay and its area of influence,” says Juan Carlos Leyva Martínez, regional coordinator of Pronatura Noroeste.

“These lands, these reserves are located in what was known as the ejido agricultural colony Mexico, this site starts from the La Reforma fishing field and the reserve extends to practically adjoining Navolato in what we know as Montelargo,” he explains. “We are in those 2,500 hectares, they are in different patches in that interval, in the center of the bay in the municipality of Angostura,” he explains.

Pronatura Noroeste Team. Photo: César Hernández.

We are with Juan Carlos and part of his team in the central area of the reserve protected by Pronatura Noroeste. A relict of thorny forest vegetation protects us from the strong midday sun, while it threatens us with the multitude of cacti and thorny plants that make up the dense landscape.

Mimosas in bloom a few meters from the limit of the reserve. Photo: César Hernández.

Blooming mimosas grow abundantly in the shade of vegetation, bird nests are sheltered among cacti, but just a few meters away from this megadiverse patch is already the agricultural frontier. A few meters behind the fence, the planting grounds begin, showing a strong contrast between the green vegetation growing due to the summer rains and the earthy yellow-brown of the dust raised by the preparation of the land in the agricultural fields.

Nest in the Thorny Forest of the reserve. Photo: César Hernández.

Unlike the agricultural land crossing the fence that delimits the natural area, this thorny forest still provides shelter for foraging rest and reproduction of terrestrial birds, as well as non-tropical migratory birds, which use it as a hibernation site.

But in addition to this thorny forest, the Reserve has other types of habitats, such as marshes and wetlands, which are equally important for the species that inhabit it and the ecological balance of the entire bay.

“In other words, this place represents a habitat, a relict, very relevant and important for more than 135 species of terrestrial birds that attend, that come, that are here on the site at some time in their lives,” explains Juan Carlos.

“For example, here we have an abandoned nest that is an example of how the site is used for nesting. That nest has passed its season, the chickens have already come out, they have already laid their eggs, but we are also going to find nests of nightclubs or chimneys on the ground; we are also going to find habitat on some plains that are important for the nesting of some birds, shorebirds and plovers, for example,” he continues.

Boundary between reserve and agricultural land. Photo: César Hernández.

What are the challenges of habitat conservation? What assessment do you make in that regard? , he is asked.

“There are many anthropogenic pressures precisely because of economic activities; although it is true that economic activities or conservation activities can coexist, pressure exists (...) that we have the agricultural frontier literally as a neighbor, it is not metaphorical. It's on the one hand. In other words, the agricultural plot that is there ends and then the Santa María Ecological Reserve begins,” says Juan Carlos.

Among these pressures, the coordinator of Pronatura Noroeste lists the growth of the agricultural frontier on the borders of the ADVC, the polluting effect of agrochemical residues from agricultural use and the effect of aquaculture that promotes habitat fragmentation.

“These are the fundamental pressures that exist here in the Bahia de Santa María Ecological Reserve,” he concludes.

“Not that much”

“Not so much as a fight, right? , but they did tell me 'hey, it's just that this is how far my property goes', but I have a role that says no,” says Antonio Ávila, field technician at Pronatura Noroeste. He is dedicated to doing surveillance work in the reserve. Their job is that of a kind of 'ranger'. That a piece of paper protects the area, he says, is no guarantee of protection.

“My job is to keep an eye on the trails, so that there are no vacant cattle, that farms are not built; because sometimes they invade a few meters under the pretext that they didn't measure well, but it's not true with an intention, sometimes a few meters enter so as not to waste space in their pond, among other things.”

“When you own a property you have to delimit and protect it, that's your duty as an owner.”

Around the reserve, he says, there are mainly agricultural fields, shrimp farms and some vacant lots of people who, for one reason or another, did not sell or make productive use of the spaces.

“I locate around six, maybe they want to make a farm (shrimp farm), but since they can't access it through a canal through the other properties, they're just there for no use, they're being preserved against their will.”

Antonio Ávila, Pronatura Noroeste field technician. Photo: Video capture.

Land without roots

Like any initiative focused on the defense of the territory, Pronatura recognizes the vital importance of involving local people under a community approach.

“We are convinced that one of the best ways to do conservation is with the support of neighbors, the people who use them for their productive activities,” explains Juan Carlos.

“We seek dialogue with all the neighbors who are both in the agricultural part and in the aquaculture part of the reserve; what we do in principle is to promote dialogue, explain to them, make them aware, tell them what an ecological reserve is, emphasize the importance in terms of habitat, in terms of integrity, in terms of what it means for ecological processes”, he abounds.

But in addition to the protection of these 2,500 hectares of coastal zone, the Pronatura organization carries out a series of activities with the community, authorities and the private sector, all focused on the revaluation and protection of the area's natural wealth.

“We do multiple management actions. For example, we do community work, we invite personnel from different communities to join work here in the reserve; we develop firewalls, which is a measure to prevent the fire from spreading if there is a socket burning.”

“We also promote with the local university, which is the Polytechnic University of the Evora Valley, that students do internships here, to help us make reforestation connections, for example.”

“We also work to promote, at the level of the Basin Council, basin management plans; that is, we are promoting the design of different instruments for planning at the basin level and we promote it with users, with farmers, with ranchers, so that these management plans can be implemented by the community or by the productive sectors.”

However, it also points to a difficulty in terms of community work, stating that much of the productive land surrounding the reserve is actually rented, which makes it difficult for them to take root in the well-being of the area beyond their productive enterprise.

“With this I can protect”

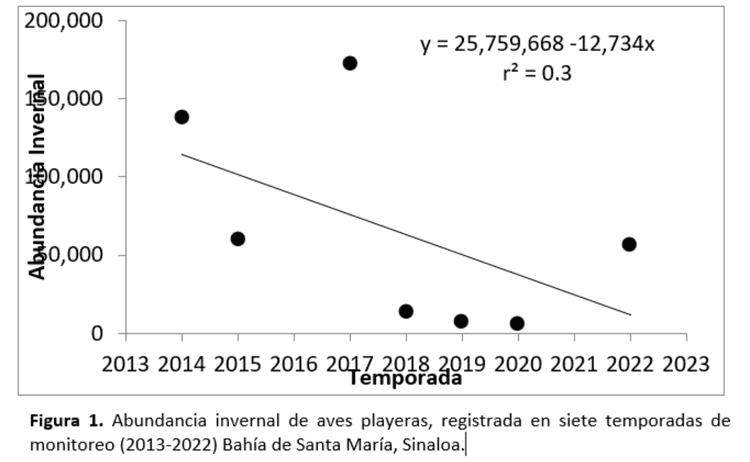

With seven years of experience working in bird monitoring in the reserve, biologist Rosa María Benítez confirms that, at the ecosystem level, there have been major changes.

“Yes, there have been big changes and birds have actually decreased quite a bit in their populations,” he says.

Change in the landscape at the RHRAP site due to the development of shrimp farming. Photo: Juanita Fonseca.

He attributes this decline in the bird population to the reduction of water bodies due to the advancement of productive activities, mainly shrimp farms.

A study by the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) confirms what the biologist said when documenting the decreasing trend of shorebirds recorded in seven monitoring seasons, from 2013 to 2022.

Image: Capture of the State of Waterfowl study in Santa María Bay, Sinaloa (2022).

“The amount of water that has been in here has been reduced. In the reserve there have always been bodies of water and then they have been shrinking as activities have progressed. Yes, it has been seen,” he laments.

Rosa María, who aroused her curiosity, love and respect for nature in those exploration adventures around her grandfather's miles, also regrets sharing her expectations for the future of the bay.

Rosa María Benítez, Pronatura Noroeste field technician. Photo: Video capture.

“The truth is that you are very disappointed in this because, yes, it is a constant struggle and in the end you have to accept that you are not going to be able to protect everything. But in the end you say, with what I can protect, that's what I'm left with. So that grain of sand that we can do. Unfortunately, you can't (protect) everything, but whatever you can rescue that is good. So here, because the truth is very shocked and well the hopes, the truth are not many. At least we can protect this area,” he says.

Boundary between the reserve and the start of aquaculture activity in the bay. Photo: César Hernández.

It is not an 'environmental idealism'

“Sometimes to be able to fix things you have to buy; I've seen it over time (...) There comes a time when the Federal Government doesn't have the money to do it or doesn't want to allocate resources, and the only way to conserve an area is for someone to buy it,” says Dr. Diana Cecilia.

In Santa María, remember, he had to do a load capacity study funded by CONANP, the result was that agricultural activity could not continue to grow.

In its conclusions, the 2013 study indicates that: “According to all the indicators used, the load capacity of the system has been exceeded”.

“Any future expansion of aquaculture facilities in Laguna de Santa María is inadvisable,” the study concluded.

This situation, he says, is largely the result of a lack of coordination between Semarnat and Sagarpa.

“If you go to Semarnat and ask for permission to build a shrimp farm, they will say no, because there is no longer any ecosystem capacity, but Sagarpa gives you permission. And then about faits accompli, well, right?” , reported.

Doctor Diana Cecilia Escobar. Photo: César Hernández.

The doctor and environmentalist defends fishing activity against accusations of overexploitation, pointing out that, in the years she has been studying things, she has seen that the number of fishermen has been maintained, but that what has fallen is the environmental quality.

“The fishermen are the same, there is no real increase in fishing, there are no more pangas, there are no more people fishing. What is happening is that environmental quality has actually decreased.”

“And then we looked at what the remediation strategies would be, we dedicated ourselves to studying this to see how we can reduce the impact, because it's not about getting angry with farmers but about looking for alternatives. That's our job,” he points out.

“It's not an environmental idealism, it's a reality that you can consult with fishing experts,” says Esteban García-Peña, director of the Oceana fisheries campaign. The environmentalist recalls that, more or less, between 80 and 90% of species depend on the good health of estuarine ecosystems such as mangroves.

The biologist with a Master's Degree in Ecology and Environmental Sciences and Comparative Public Policy affirms that, unlike the convenient official narrative, the cause of the deterioration of the coastline of the bay is not only overfishing, but also the destruction of habitats such as mangroves, coral reefs, estuaries and other natural areas that function as a true cradle of species; as well as pollution by agrochemicals and urban waste. “Anyway, just imagine all the sources of pollution that reach the water and directly affect the development of species,” he concludes.

Regarding the protected area in charge of Pronatura, García-Peña recognizes the organization as a pioneer in this type of project.

“In the 90s, ProNatura began with this strategy of establishing areas of ecological servitude,” he says.

“All this gave rise to what were later called the ADVC's, the areas voluntarily dedicated to conservation,” he points out and adds that one step that is missing to promote this type of reserve is to define resources for their proper management.

“The federal government would have to define resources because then there are people, there are ejidos who don't have the resources to do maintenance, inspection, surveillance, care, restoration,” he explains.

Esteban García-Peña, director of fisheries campaigns at Oceana. Photo: Courtesy Oceana.

It also recognizes the conservation strategy as fundamental.

“The fact that you have an area where a bird can perch or can nest or can rest, or a mammal can hide or can have a shelter, can reproduce is essential for the marine ecosystem, it's not just water with fish and mollusks.”

“The marine ecosystem is also something that depends on what flies, what it carries, what is out there,” he emphasized.

A tool for sorting

Navolato is actually the Sinaloa municipality that occupies the largest area compared to the area proposed for conservation in the 2012 ANP supporting study. This document proposed an area of 35,400 hectares, 52 percent of the 67,000 hectares proposed.

The Director of Urban Planning and Environmental Management of the municipality, Cristian Yarely Díaz Sánchez, points out that, after a series of studies and analyses, they concluded that Navolato lacks a 'legal instrumentation' to help it solve problems detected in the Bay of Santa María, such as overexploitation and damage to biodiversity, as well as conflicts over land use. “So we decided to start what is the topic of ecological planning,” he says.

This ecological order, he assures, will be like a kind of territorial planning, but prioritizing the environment.

“It's not about diminishing the development of the municipality, on the contrary! The point is that, if there is going to be a development, it is orderly and always prioritizing the environmental issue.

The law will help us do that,” he promises.

“Determining what areas are viable for and how it can be done, so as not to destroy what we have and to determine the areas to conserve”, abounds.

This regulation would be “the first legal instrument that can be worked with within the Bay of Santa María”.

“We definitely believe that it will be the first legal tool that we will have or that we will have as a reference for work and conservation within the country,” he predicts.

Director of Urban Planning and Environmental Management of the municipality, Cristian Díaz. Photo: César Hernández.

For now, this ecological system for Navolato is preceded by the formation of a technical committee, composed of representatives of all the actors with some relationship with the area and an existing executive committee made up of the authorities, who will be the bodies responsible for evaluating and approving this regulation this year.

“On the contrary, we believe that Navolato now brings important development in the coming years, but that's precisely why we want to bring order and prioritize it, because the environmental issue isn't it? which is so important”, he points out.

For this report, the Department of Environment of Angostura was also contacted, a municipality that accounts for 32% of the areas of the bay proposed for conservation; however, an interview could not be carried out.

Do the people who live here Chinitos, La Reforma, Gato de Lara, and the surrounding villages, know that this is a protected reserve?

“Some people locate it, but no, they don't measure what it refers to; you try to explain it to them and for many of them it doesn't make much sense because everything for them is to take advantage of things,” replies Arturo Ávila, ranger of the Pronatura Noroeste reserve.

“For a person outside conservation, it is difficult to explain exactly the purpose of what is done in this reserve,” he says.

His opinion contrasts with what, during his last visit to Sinaloa with Oceana, Esteban García-Peña was able to confirm when talking with groups of fishermen. “The fishermen with whom we had meetings, and many of them don't just think about the bugs that are in the water to fish; they think about the ecosystem, they think about the bird that needs to be there, about the marine mammals, they already think in a comprehensive way.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Diana Cecilia emphasizes the need to, as do wildlife and even some social groups, mainly indigenous groups, to learn to stop preying and maintain a balance between industrial production and reproduction of natural ecosystems.

For his part, Juan Carlos Leyva believes that, in the very near future, all that will remain of Santa María Bay will be this reserve of 2,500 hectares purchased by a civil organization and voluntarily destined for conservation.

***

* This work was supported by the Maritime Journalism Network (Repemar), promoted by Causa Natura Media.

Comentarios (0)