The sound is a zum, zum, zum. Giant towers with three blades that rotate endlessly line the landscape. Along the way are the road, the fields and the army of wind turbines over 100 meters high that form wind farms. Zum, zum, zum, as the wind feels strong and the voices are heard underneath everything.

When entering the town of Unión Hidalgo, the towers are left behind and the road turns into paved streets and many other dirt roads. The houses are single-storey with cobblestone, cement or sheet roofs. Nothing is extravagant or luxurious in this Binnizá (binni, people; zá, cloud: people who come from the clouds), also called Zapoteca, belonging to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec region, in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico.

Still, life has changed. Its inhabitants say that working the land and cattle no longer works as before, that the water from the wells is scarce, that because of this deterioration several people have migrated, that even the birds have changed their routes.

The installation of wind farms, once the promise of development, became a resistance of more than a decade. In this time, everything from deceptive contracts to violence and pollution has been documented. The current environment is one of uncertainty, but also one of firmness.

The voices of those who live on the Isthmus are resounding when they say that they will not accept more wind projects. Meanwhile, companies that install wind turbines are being recognized by other countries for making wind electricity. The support is with renewable energies (which come from the sun, air and water, among others) because they are considered allies against the climate crisis.

Bimbo, Chedraui, Walmart, Nissan, Cinemex, Oxxo and Cervecería Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma are some of the dozens of companies that appear to be beneficiaries of wind power production. For specialists, organizations, and even land defenders, the problem is not that industries use renewable sources, but rather what this energy generation has done to communities' livelihoods over the past 12 years.

Causa Natura Media contacted the wind companies mentioned in this report, but only a response was received from the Spanish company Iberdrola stating that it will not comment on the matter. Communication was also established with the Mexican Wind Energy Association (AMDEE), which replied that it will not respond to the questions raised.

Wind and energy for whom

When Guadalupe and other residents of Unión Hidalgo came to Oaxaca de Juárez, for the first time in 2011, to seek solutions to the wind power that was being installed on their communal lands, the authorities told her that they were lucky in their town because a company had arrived that would change their lives.

It all started two years before that visit to the capital of Oaxaca. Guadalupe, then 58 years old, and around 70 other people had signed contracts with Desarrollos Eólica Mexicanos (Demex), then a subsidiary of the Spanish company Renovalia Energy, which was looking to install the Piedra Larga wind farm.

“We signed the contracts in 2009 and in 2011 was when the construction of the wind farm began. We realized that it was not what was expected, it was not what had been discussed. They only destroyed,” recalls Guadalupe Ramírez, from her home in Unión Hidalgo.

In addition, the contracts were not what had been agreed upon either. Since these were communal assets (a type of agrarian land that is governed differently from the territory formed by the states), the community had not been consulted nor had a clear legal process been carried out.

“We realized that our land was mortgaged. We no longer had the right to work the land. Now it was they (the company) who could do and undo. Without realizing it, with our own hand we signed and said yes, we handed them everything in a silver tray,” Guadalupe recalls.

In those years, the communities of the Isthmus talked about development, energy generation and new opportunities for a people whose life had always been land and field. That was the information they had available and that they agreed to sign for.

When the complaints began, companies and state authorities held a couple of meetings to discuss the terms of the contracts, but they didn't budge. Of the 70 people who had signed, half decided it would be best to leave things as they were. Continuing to spend on trips so as not to get answers was not within their means.

“This is how sometimes we lose our struggles, due to lack of resources to be constantly going to Oaxaca (capital) to be treated. It wasn't because the others didn't want to defend their land, but because there wasn't enough money. It's very sad to know that the colleague cannot go because of lack of resources,” says Guadalupe, who 12 years after that first mobilization is now one of the leading defenders for her community.

Those who decided that they would remain in the defense to recover their lands, that same year contacted the organization Proyecto de Derechos Econócos, Sociales y Culturales A.C. (ProDESC) for legal support.

After a nine-year litigation, in 2020, the Unitary Agrarian Court of District 22 of Oaxaca declared the definitive nullity of contracts in favor of 11 people, including Guadalupe Ramírez. Demex would have to return the corresponding land, but the wind farm could continue its activity regularly in areas where the contracts had not been appealed, as it had been since its start of operations.

Currently, there are two permits for power generation granted to Mexican Wind Development, in accordance with requests for information made to the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) for this report.

These permits are those that establish the megawatt (MW) capacity, the description of the facilities, the partners who will receive that electricity supply, the validity of the permit, and other agreements.

Most of the wind turbines were processed under a self-supply model, which meant generating electricity in their own plants without depending on the supply of the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). And although the self-sufficiency category legally disappeared with the energy reform of then-president Enrique Peña Nieto in 2013, the permits were not immediately canceled since a transition period was established.

The current president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has been critical of this, assuring that companies maintained their profits and that their partners “pay less in electricity than a grocery store”. So he decided to accelerate the cancellation with an electricity reform that has been stopped under the protection of some companies that argue the loss of competitiveness and the relegation of renewable energies.

In the case of the permits granted to Demex, both belong to the industrial estates that form the Piedra Larga wind farm. Except that the first one occurred since 2009, with the Spanish company Renovalia Wind as its leading company, and the second in 2012, known as Piedra Larga Phase 2, under the Spanish company Gamesa.

In the case of Renovalia Wind, permit E/823/AUT/2009 describes a wind power plant with 152 wind turbines divided into two polygons. It has 27 partners for the demand for this energy, including companies such as Suburbia, Barcel, Ricolino, Bimbo and Walmart.

On behalf of Gamesa, the Piedra Larga Phase 2 park was granted the E/939/AUT/2012 permit for a power plant with 60 wind turbines and a total maximum capacity of 137.50 MW. Its partners are Walmart, Suburbia and Vips.

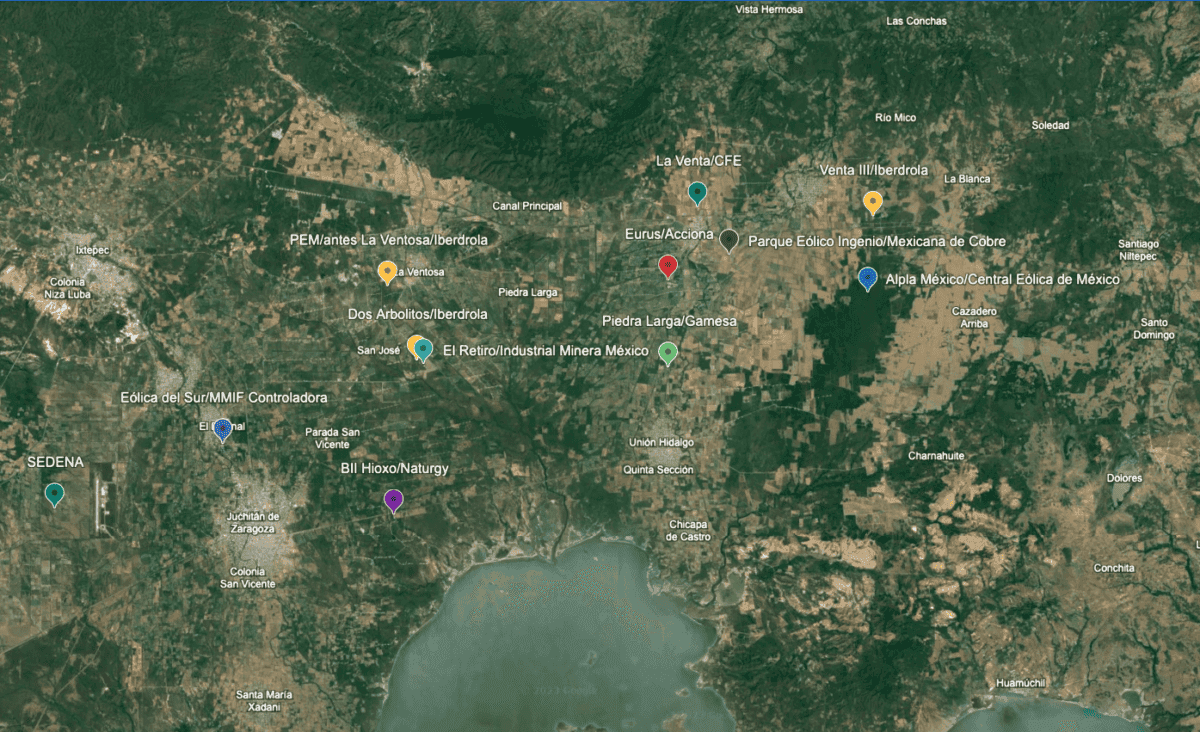

Piedra Larga has been followed by dozens of parks in the region. According to information from the CRE provided through transparency, there is currently a register of 28 permit holders distributed among the towns of Juchitán, Unión Hidalgo, La Venta, La Ventosa and El Espinal. The permit holders represent the parks that currently exist in this area.

Of the total, 13 are owned by Spanish companies such as Accion, Gamesa, Iberdrola and Naturgy, which use subsidiaries to act as permission holders. There is also a project by the Austrian company Alpla, one by the American company Walmart, one by the Italian company Enel Green Power and another by the Japanese company Mitsui in alliance with the French company Electricité de France (EDF).

What makes the Isthmus of Tehuantepec such a coveted area are the strong winds that hit this region. And despite the conflicts with its inhabitants, the investment commitment continues. In February of this year, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said that he planned four more parks with support from the United States government.

“The issue is not whether wind projects are put on or not. The issue is how to regulate the installation if you already have 28 parks in the region that, in addition, are exceeding the capacity of electrical transmission networks,” explains Juan Antonio López, coordinator of Transnational Justice at ProDESC and companion of the legal battle of Unión Hidalgo.

“If you have damages that are already affecting the regional system, the environment, health and the social environment more widely. Would it be ideal to put more parks there?” , questions.

Bad practices

Guadalupe Ramírez remembers the sound of detonations. It was a few months after I decided that I would not accept the contract for the Piedra Larga wind farm. She was traveling with her family members through Unión Hidalgo when two vans were placed in front of and behind the vehicle in which she was traveling. It was there that he heard the sound of the gun firing from one of the cars.

“The first thing companies do is surround themselves with people who defend them, who frighten all people. We know them and if we talk about last names, we already know that he is a guy and we have to be afraid of him,” Guadalupe says.

Since those years, threats and intimidation have not ceased. In addition, residents and defenders have denounced the increase in organized crime in the area.

In the town of La Ventosa, located just 20 minutes from Unión Hidalgo, German Valdivieso, 30, says that everything has changed in the dynamics of the Binnizá community. With the beginning of the defense, the division between those who gave up their land and those who were still in denial was notorious. The latter were intimidated by detonations of weapons, anonymous calls and persecution.

“Wind energy doesn't just bring promise, they bring insecurity, they bring other things that people avoid saying. We have been threatened and that's why we tell others and take action because even access is not free,” says Germán, a member of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus for the Defense of Land and Territory.

In 2018, the French company EDF Renewables made a consultation for the installation of a 300 MW wind power plant, located near La Ventosa, which it called Gunná Sicarú. The park would be suspended in 2021 after a series of irregularities reported by defenders of Unión Hidalgo and ProDESC.

Defenders interviewed for this report agree that people who disagreed were silenced during the consultation. They were not allowed to speak or if they took the floor the screams and boos began.

“At the root of the problem is the systematic violation of human rights involved in the installation of these projects. What we mainly see is the violation of free, prior and informed consultation, but there is also a violation of the right to self-determination of peoples,” explains Ángeles Hernández Alvarado, collaborator of the Observatory of Socio-Environmental Conflicts of the Ibero-American University (Ibero).

The Observatory has documented this and other land defenses in Mexico. In the case of the Isthmus, queries have been detected that are only made to meet the requirement. Often there is the presence of people who are not from the communities. In addition, these processes are carried out in Spanish when communities speak Zapotec.

“For the EDF Renewables consultation, they (the permit holders) met with certain people who claimed to be landlord leaders (of the land) and in turn they convinced other people by paying 200 to 500 pesos to attend the meetings,” recalls Juan Antonio López, from ProDESC. This is for the purpose of voting in favor of the project.

On the Isthmus, some of the oldest parks are related to these practices and irregularities. For example, Bii Nee Stipa, bought from Gamesa in 2011 by Iberdrola, has been controversial.

Journalist Diana Manzo documented how in 2015 a 47-hectare owner accused the company of dispossession, death threats and default for two years equivalent to 150,000 pesos.

According to information obtained through transparency, this park has had a permit since 2006 and began operating in 2010. Its wind power plant consists of 31 wind turbines with a total capacity of up to 26,350 MW. And its partner is the Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma Brewery with headquarters in Orizaba, Veracruz; Navojoa, Sonora; Guadalajara, Jalisco; Puebla and Chihuahua.

A similar case has occurred with the permit holder Fuerza y Energía BII Hioxo, from the company Naturgy. A plant with 252 generators whose main partners are Cementos Moctezuma and Tiendas Chedraui with 47 offices distributed in Puebla, Guanajuato and Veracruz.

In 2017, collective amparos were filed and signatures were collected against this park for violations in the consultation, as well as forced evictions by police during demonstrations in the areas surrounding the facility.

“The thing is that (companies) continue to deceive and pay a crumb to those who sign contracts. In some cases they say it will improve the light supply, but that's not true. There is no development, as they call it. For us there is no development, only conflicts,” says Germán.

One of the complaints is that although energy is generated in the Isthmus, 15 of the 28 permits fall under the category of “diverse industries”, which include power plants with partners that demand energy for industrial activities. The rest is established as an “independent producer” or as a “generator”, as is the case of the plants of the Federal Electricity Commission.

For example, the Spanish company Gamesa, in addition to Piedra Larga Phase 2, has two other permit holders under the name of Eólica Zopiloapan, in the town of El Espinal, and Environmental Energies of Oaxaca, between Juchitán, Santo Domingo Ingenio and Cazadero.

In the case of Zopiloapan, its power plant consists of 35 generators with partners such as Nissan, Nestlé, Apla Mexico and CPW Mexico. Meanwhile, Environmental Energies of Oaxaca generates electricity under the category of “independent producer” for exclusive sale to the Federal Electricity Commission.

However, specialists contacted for this report believe that the main problem is the actions surrounding this energy generation.

“Of course we believe that we should bet on a different generation of energy, but there are several fundamental things there and one has to do with inequality. On the one hand, we talk about the fact that these energies seek to alleviate the effects of the climate crisis, but they have direct consequences in these communities where social and ecological impacts are being promoted,” points out Ángeles Hernández, from the Ibero Socio-Environmental Conflicts Observatory.

In addition, the generation of electricity through wind power in Mexico is still minimal compared to that obtained from other sources. According to official figures, in 2020 it represented only 5.88% of total energy generation.

Measuring impacts

It was that noise that motivated Rosalva Fuentes to join the defense that was being formed in her town. Used to sleeping in a hammock outside her house, with only the chirping of crickets and blowing air, hearing the sound of wind turbines for the first time was disturbing.

“The first time my mom also woke up and with great surprise she told me it was the sound of wind farms,” Rosalva, 54, recalls from her home in Unión Hidalgo.

The incessant noise, the damage to community water wells, the pollution of rivers such as the Holy Spirit, the death of animals such as bats and the change of route of migratory birds that used to fly over this region, are all attributed to the saturation of wind farms.

Despite the fact that official company websites ensure that parks do not interfere with the activities and life of communities, their inhabitants say the opposite.

“Wind energy can be good, I don't know, but it's not the right way to develop them. You can see that they invade land, dig deep and put in a lot of cement (for infrastructure). Waters are diverted and there is no natural way for them to pass into rivers and wells. I wonder if in 30 years we will no longer have water”, describes Rosalva.

In Juchitán, the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus for the Defense of Land and Territory believes that in order to respond and explain these environmental phenomena, a regional study of the cumulative impacts is urgent in order to determine what will be the solutions and the repair of the damage that has already been caused.

“Our position is clear that we don't want one more wind company, any more industry, because there are no real benefits for communities,” says Mario Quintero, one of the members of this Assembly. To his voice is added that of the defenders of Unión Hidalgo, La Ventosa and La Venta.

While specialists believe that moving towards a just transition will require weighing the results. But to date, there are neither studies nor official answers that can provide clarity.

“This energy transition and this push for renewable energy cannot be for some at the expense of others... If you ask me the ideal scenario, then it would be with processes that involve the adequate participation and consent of the people who are going to be potentially affected,” adds Ángeles Hernández, from the Ibero Observatory.

Meanwhile, the giant towers with three blades continue to rotate non-stop. Zum, zum, zum, while the wind is strong and the Binnizá communities continue their organization with the conviction that no more projects will arrive.

Comentarios (0)