Illustration: Esteban Silva

Opening the faucet and letting the water run daily is something that has never happened in the Ciudad Cuauhtémoc neighborhood. Washing, cooking and taking a bath are needs conditioned on the days when the water arrives. In dozens of houses in this neighborhood of Ecatepec, in the east of the State of Mexico, nothing has been going through the pipe for two months.

Life has been like this for more than 30 years.

When the water comes, it's at night. Revealing to clean and collect as many liters as possible became a habit. The rest of the month, it is rationed into drums and tanks, it is reused up to three times, bottles are bought and, when there is money, pipes are paid for.

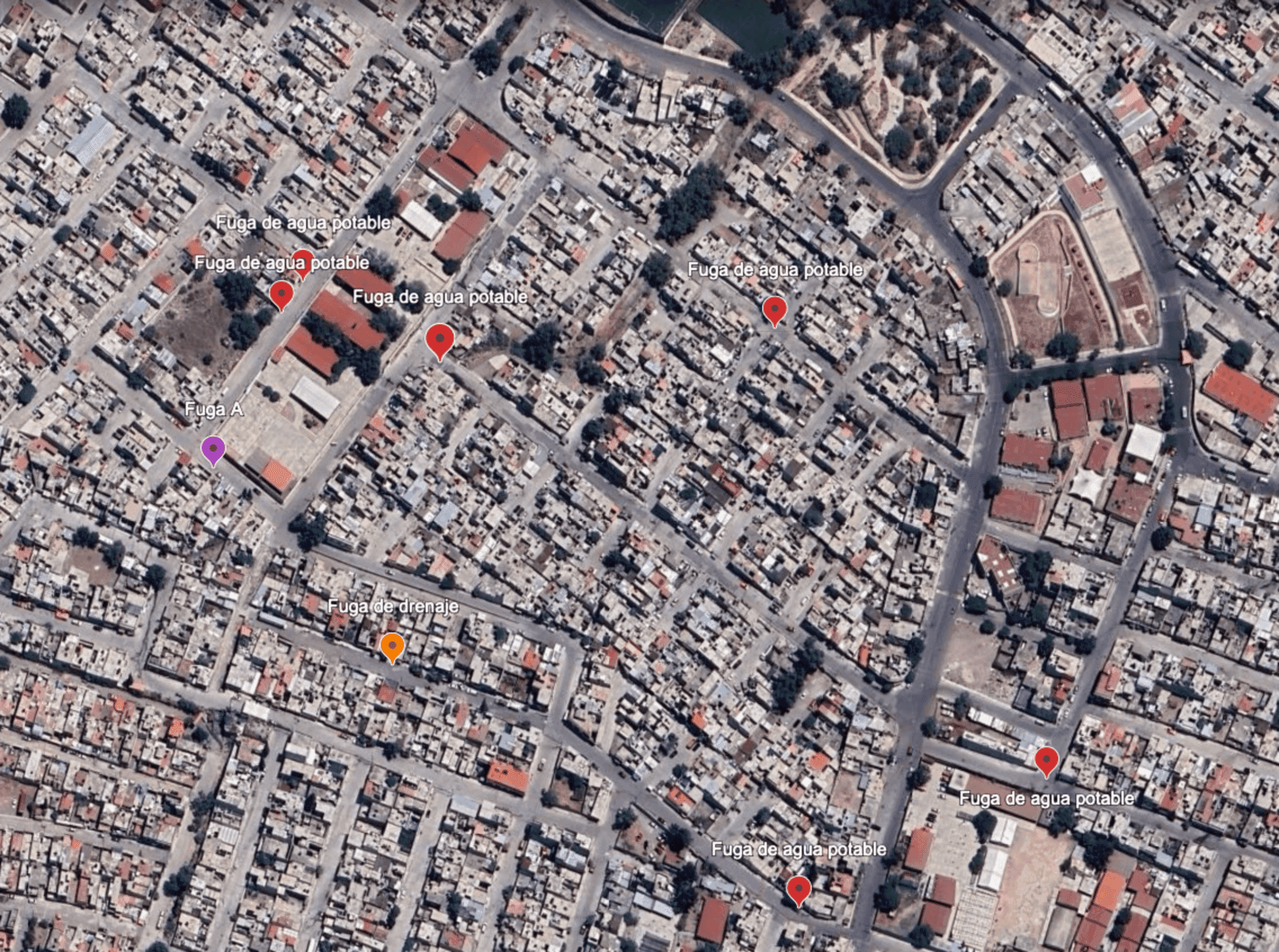

Neighbors find it interesting that when water comes out of the faucet, it also sprouts in the streets. Leaks of clear, odorless liquid, mix with the drain and run down steep avenues. Despite neighborhood reports, they have not been repaired for so long, that we already know where they are. One on this street, one on the corner, three more on the next block.

Several times they have seen water come out on the street rather than in their own homes.

In a neighborhood like Ciudad Cuauhtémoc, where water is not an everyday right, seeing waste on the streets is disturbing for its inhabitants. A reality that is repeated in other neighborhoods of Ecatepec; in other municipalities in the State of Mexico; and in other states, such as Guanajuato, Mexico City, Nuevo León, Sinaloa, Querétaro and Tabasco.

On average, 40% of the country's drinking water sent through the pipeline is lost in leaks, researchers from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) document. Leaks are not the only cause of the shortage, but they are the symptom of a deteriorating hydraulic infrastructure.

Behind the numbers are water systems that go months without attending to a leak. These can last so long that sinkholes form.

The increase in demand for water, unplanned construction and seismic zones are also factors that increase the likelihood of leaks. While some solutions are being proposed, the institutional staff and the budget allocated to pipe repair are being overcome.

For this report, more than 600 requests for information were made to the water systems in operation and the five most populated municipalities in each entity with the objective of measuring water loss in the national hydraulic network.

The National Water Commission (Conagua), the Drinking Water Sewerage and Sanitation Service of Ecatepec de Morelos (Sapase) and the Mexico City Water System (Sacmex) were contacted for more information on network maintenance and citizen reports, but until press time there was no response.

Ecatepec, between losses and inequality

Elisa Espinosa moved from Veracruz when she got land in the Ciudad Cuauhtémoc neighborhood 40 years ago. “I liked it because it looked like a field,” he recalls as he walks through the streets full of houses, half colored facades and half black work. The colony was built at the foot of the hill of Chiconautla, one of the nine founding towns of Ecatepec.

From the start, there was no water. The neighbors went down the avenue to fill their drums with the pipes sent by the municipality. At that time it was not worrying because the colony was just being populated and there were plans to build a hydraulic network.

“But even when they put on the net for us, it didn't come daily. At first it fell every 8 days,” Elisa recalls.

Currently, the water supply takes an average of one month, sometimes extending up to two or more. Public pipes no longer arrive when they are ordered and private pipes only agree to leave the supply when it comes to large quantities such as complete tanks. No buckets, no drums, not half filled. The monthly costs amount to 3,500 pesos.

“It's spending on what we don't have,” Perla Serrano, who has lived in the colony for 21 years, tells a group of neighbors. Everyone present, including Elisa Espinosa, nods.

These are five women, sitting on the edge of the sidewalk, protecting themselves from the midday sun, gathered to talk about how the shortage is going after the presidential elections of last June 2. The answer is the same: the water hasn't arrived.

For years, they have all been organizing offices to Sapase, which is the agency responsible for drinking water, sewerage and sanitation services in Ecatepec. One of their main demands is the maintenance of the pipeline to mitigate leaks.

Most of the time, the body's actions are delayed or null.

In the water leak records provided via a request for information for this report, Sapase recognizes the lack of attention paid to the maintenance of the hydraulic network in Ecatepec.

In 2023, Sapase only dealt with 45% of water leaks in the entire municipality. Out of a total of 5,957 reports, 2,682 were repaired.

There are records of leaks dated January 1, 2023 that until April 2024 continue with the status: in the process of being treated. Response time was no more effective in previous years. In 2022, only 19.1% of the reports were repaired. In 2021, they reached 44%.

The Sapase Transparency Unit explains in its response that “the time between reporting and repair, nor the amount of water leaked, has not been estimated.” However, the dates of the reports indicate that it takes from 24 hours to a month to remedy the pipeline. Some are more than half a year old, and then there are those that have not been attended since the previous one.

“We have three escapes on this street that we have been, without lying, for six years reporting them and they haven't been able to come because they tell us that they have no material, that they have a lot of leaks to deal with, that (they will come) until it's our turn... It's never been our turn,” Perla explains as she extends the copies of the letters they sent.

“We hereby address you with the due respect you deserve to ask you in the most attentive way to support us with the change of the pipeline,” begins one of the documents, dated June 30, 2021, addressed to the municipal president of Ecatepec, Fernando Vilchis.

The problem in numbers

Ecatepec is the first municipality with the greatest neglect of water leaks. But in terms of quantity, it is the fifth place in the State of Mexico.

Tlalnepantla, a municipality that is also part of the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City, has ranked first in the state since 2021. The annual average is 14,500 leaks per year.

This is followed by Tecámac and Naucalpan with an average of 8,000 annual escapes, and then there are Cuautitlán Izcalli and Ecatepec with an estimated 5,000.

If we speak at the national level, the numbers double. In 2023, the city of Culiacán, Sinaloa, reported the most water leaks in the entire country with 35,866 leaks. This was followed by Tijuana, Baja California, with 32,000; Monterrey, Nuevo León, with 23,113, and Ensenada, Baja California, with 21,664. Only in that year.

Meanwhile, from January 2019 to April 2024, the city with the most escapes is Hermosillo, Sonora, which accumulates 255,826.

For this report, the Causa Natura Media journalism team requested the causes, the liters lost and the length of time the leaks lasted, but not all municipal water systems have a breakdown of the information.

Several of them don't even keep a record of escapes, such as Valparaíso, Zacatecas; Tanquián de Escobedo, San Luis Potosí, and Pueblo Nuevo, Durango. While most do not have a history of past administrations, so data before 2019 is scattered.

In other cases, there are municipalities that do not have their own water system or an area in the local government that responds to the problem, so it is unknown what their situation is with respect to the hydraulic network.

More leaks don't always result in more wasted water. Of the 508 municipalities consulted for this report, only 40 keep track of what was lost. If we consider only the information provided for this sample, in 2023, at least 38 billion liters were leaked in the primary and secondary network. Enough to fill three million 800 thousand pipes or 15 thousand Olympic pools.

However, almost the total of this figure corresponds to Tabasco, since it is the only entity that keeps an estimated measurement of leaked water. That year it reached 36 billion liters in 15 of its 17 municipalities.

At the level of regional water systems, the Cutzamala System, which supplies Mexico City and the State of Mexico, has lost more than 31 million 600 thousand liters from 2021 to April 2024, according to information shared by Conagua via transparency.

The causes are usually damage to the pipes due to their age and lack of maintenance. Some external factors include buildings and the constant flow of cargo vehicles that generate pressure on the floors.

These leak reports do not include intentionally caused damage. In recent years in Mexico, there has been an increase in the so-called “huachicoleo of water”, thefts of drinking water in different parts of the infrastructure carried out by people for their own benefit or that of third parties.

Movements on the floor

“All the infrastructure is not ready to withstand the gradual deformation of the terrain,” says Wendy Morales, an academic at the Institute of Geology of the UNAM. “In the center of the country we see permanent subsidence and how millimeters are increasing every month. It's a constant for decades, permanent damage to infrastructure,” he said in an interview.

As a geologist, Morales sees the loss of water from natural soil factors. Sinks, landslides, earthquakes, and others have an impact on the national hydraulic network. This also causes the leaks. To which is added human activity.

“In the end, we have to associate that many of the geological hazards are socio-natural. They occur naturally, but there is an effect on the human side that potentiates them,” says the academic.

An example is the excessive construction of buildings, corporate buildings or large infrastructure projects that represent a burden on the ground. In central Mexico, where the foundations were laid centuries ago on a lake, every peso counts.

“And in that sense, not only is it the burden you place on the ground when it comes to building more, it also implies that they require more services, and by requiring more services, it leads to overexploiting the aquifer, increasing these geological hazards,” Morales explains.

Money, money

To find solutions, the immediate answer seems to be the budget.

Last January, the government of Mexico City reported that to reduce service times, from January to November 2023 they had invested 12 million pesos to deal with 11,138 escapes. Faced with questions about scarcity, there is talk of enabling wells, building new ones and placing more dams, but plans focused on the rehabilitation of what already exists are left out.

In places such as the Iztapalapa city hall, water distribution modules are currently operating where residents can request pipes. In the neighborhood of San Juan Xalpa, near Cerro de la Estrella, between 40 and 60 leave daily, from 9 in the morning to 4 in the afternoon, to supply those who have problems with the supply.

“But what we want is mains water,” says one of the neighbors in line with the module.

In other entities such as Sinaloa, which also have a large number of leaks, in 2023 Governor Rubén Rocha Moya declared that they had an unprecedented investment in hydraulic infrastructure thanks to the 27,809 million pesos that the state government would receive from the federal government.

In Nuevo León, officials' statements are similar. In December 2022, Governor Samuel García announced that over the next two years there would be projects with private investment to improve and expand drinking water and sanitation infrastructure. A total amount of 627 million pesos.

But the measures have not yet had an impact on reducing leaks and in some other states the budget is not enough for large investments.

In the State of Mexico, the government recently announced the “Women Plumbers” program in which 75 women from Ecatepec, Tlalnepantla and Valle de Chalco would be trained to learn how to repair leaks in their homes. Although most of the losses occur on public roads.

“The situation is very complex. You can't just see it from one area. We cannot say that changing the entire infrastructure will solve the problem. This is something that has to do with how we are using water, for whom it is distributed, the education we have for consumption...”, says academic Wendy Morales.

Every year in the Federal Expenditure Budget (PEF), money is allocated for drinking water, sewerage and sanitation infrastructure. The same is divided into conservation actions for the Cutzamala System, in the Valley of Mexico; the intermunicipal network for Yaquis communities, in Sonora; the construction of the Libertad Dam for supply in the Metropolitan Area of Monterrey, Nuevo León, among others.

Although the PEF increased by 69.1% from 2022 to 2023, by 2024 it decreased by 45%.

For the specialists interviewed for this report, beyond the budgetary aspect, the problem is the action plan.

“It is possible to know how much water we are extracting, but we don't have how much water is reaching each home and how much is coming out. We don't have enough meters to know 100% how much water we're losing,” explains Claudia Rojas Serna, a researcher in the Department of Process Engineering and Hydraulics at the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM) in Iztapalapa.

For the researcher, the first step is to obtain definitive information on profits and losses. A key step that has not been taken.

“The first thing we should do is to be able to know how much water is reaching homes and also to each of the industries, because even industries don't have a reliable meter that tells us how much water they are using,” Rojas adds.

In the study “Water Perspectives in the Valley of Mexico”, prepared by researchers from the UNAM Water Network, it is noted that lack of information inhibits social participation and that there is greater openness to solutions.

“In general, there are problems with regard to the availability, quality, access and dissemination of the necessary information, not only for decision-making but for the development of research projects, as well as for participation processes, and this results in a lack of trust in authority,” they indicate in the study.

Recently, the UNAM published as a success story that a group of university entrepreneurs in Chemical Engineering and Civil Engineering had launched the company “Tubepol”, to create a completely new infrastructure within a damaged one without digging too much.

On some other occasions, it is the same neighbors who pay to remedy the pipes or organize to do so with their own tools.

The proposals and resources are, but they seem scattered.

...

When Elisa Espinosa is asked if she ever thought about moving when the supply didn't arrive, the refusal didn't come. She says she would be happy if she had daily water and a room upstairs in her house to watch the night. The height at which Ciudad Cuauhtémoc is located means that when the landscape darkens, it is only the lights that illuminate the capital and its surroundings. A viewpoint view from the depth of Ecatepec.

“I tell my children that would be fine with that,” Elisa reaffirms.

The rest of the villagers think the same way: they are not going to leave the place where they built their homes. They have found a way to resist for years without water arriving every day and what remains is the conviction to find solutions. Even if there are only five of them at today's meeting, as they acknowledge with sorrow and annoyance.

“Hopefully we know more about this and they can do something, because here care is not the same for everyone,” says Perla Serrano in front of the group of organized neighbors. All those present, including Elisa Espinosa, are supported by a yes.

*This is the first report in series #RedEnAbandono, a special about the loss and damage surrounding the hydraulic infrastructure in Mexico. Originally published in Causa Natura Media.

Comentarios (0)