At least four months a year, large shrimp fishing boats in Mexico must remain docked at the docks to allow the species to recover in fishing areas.

During the dry season, which varies depending on the marine region, different commercial shrimp species grow and reproduce.

This standard, regulated by the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Commission (Conapesca), is essential for the sustainability of one of the country's most important fishing resources.

However, between 2020 and 2021, more than 365 deep-sea vessels dedicated to shrimp fishing may have broken the regulations, extracting resources during the restricted time, according to data from the Satellite Localization and Monitoring System for Fishing Vessels (VMS System), registered by Conapesca.

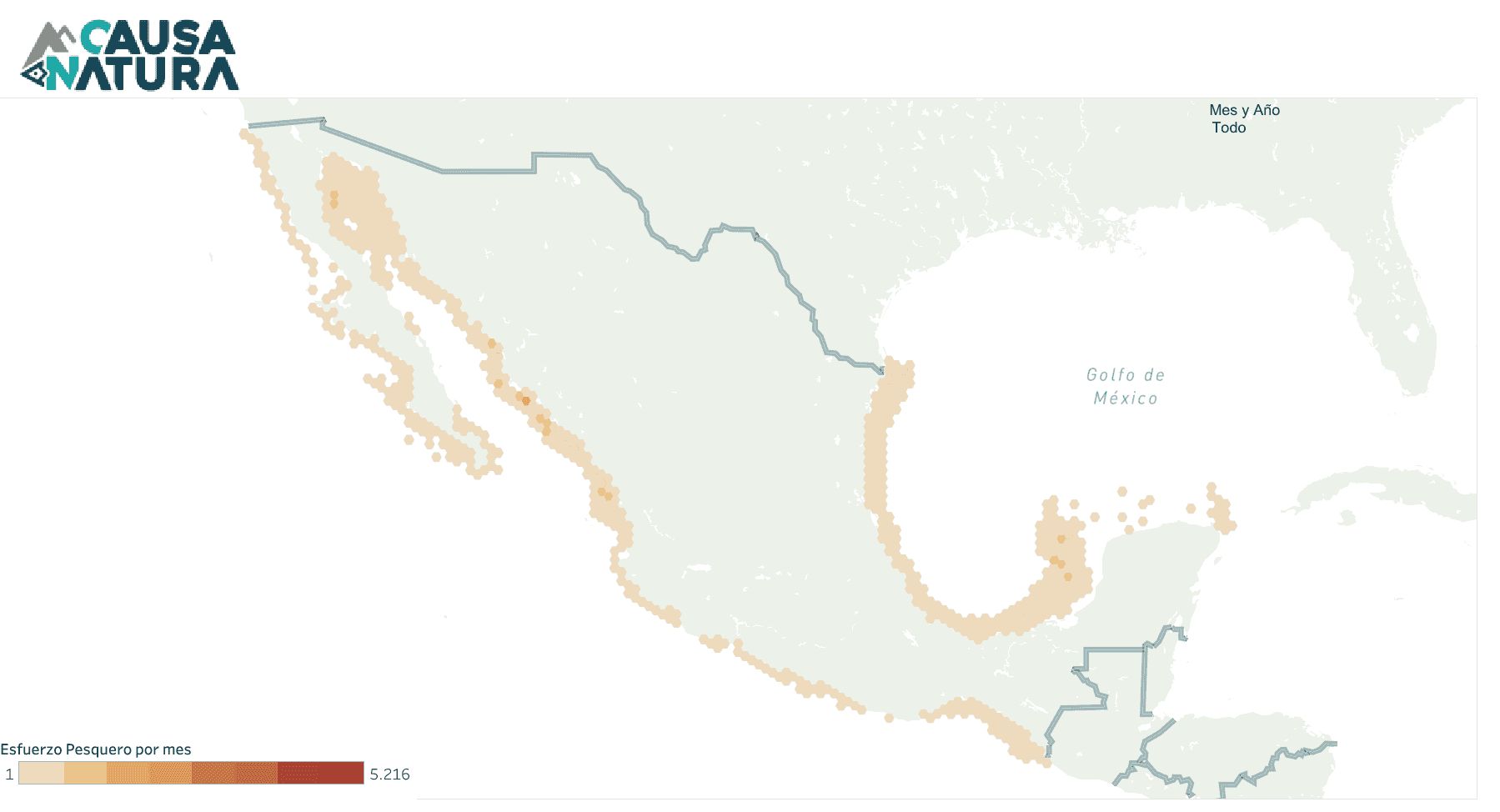

An analysis of the Natural Cause Data Unit, with open satellite data and requests for transparency on permits, reveals that there are irregularities in compliance with established prohibitions in practically all regions of Mexico.

According to the data provided, in 2020 and 2021, 18,234 possible fishing spots were registered during closed seasons. These are satellite signals that reflect the frequency with which boats enter these areas at a speed, depth and position that suggests that they are fishing.

Monitoring shrimp boats during closed season

How do you know when a shrimp boat is fishing illegally?

Ships that go out to the high seas to search for this seafood must have a permit granted and regulated by Conapesca. These are ships that, due to their size and engine capacity, are considered “larger boats”. For this fishery, the trawling technique is used, which, as the name suggests, consists of dragging a net on the seabed to capture these crustaceans.

Since 2007, all permit holders of such vessels are required to have a Satellite Tracking and Monitoring System for Fishing Vessels, as established in Official Mexican Standard 062-PESC-2007. A set of equipment and technology allows obtaining information about the position, speed, course and location of a fishing vessel, 24 hours a day and 365 days a year.

A boat is considered to be suspected of fishing when, according to the signals of the VMS System, there are characteristics that are suitable for this purpose. If it moves at an operating speed of between 1.5 and 3.5 knots per hour (low speed to facilitate trawling), in an area with a depth between 9 and 200 meters, the boat is in optimal fishing conditions.

All the vessels monitored and included in this analysis are only allowed to fish for shrimp, of no other species, so they must remain docked at the pier throughout the closed season.

The periods are defined by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (Sader), on which Conapesca depends. The vetoes are divided into two major maritime regions, the Pacific and Gulf of California and the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, which in turn are divided into subregions.

In the case of the Pacific and Gulf of California, the restrictions are between the months of March and September, while for the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea they are from May to September. They are applicable both for offshore shrimp fishing and for coastal fishing.

In Mexico, there are 976 commercial concessions to catch shrimp on the high seas, according to data from Conapesca.

Based on VMS records, during 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, 11,501 possible fishing spots were detected during the shrimp closed seasons carried out by 394 vessels, owned by 168 permit companies.

By 2021, intrusion during the closed period was significantly reduced, but 365 vessels, from 149 companies, were detected.

Ángel Castillo Novelo, representative of the Campeche Offshore Fishermen's Federation, explained to Causa Natura that during the restriction period, the Harbor Master does not grant exit permits, except for maintenance work, to test machines a few days before the ban is suspended. To this end, he points out, they are not allowed to sail for more than an hour or go more than 10 miles from the coast.

Conapesca, in collaboration with the Secretariat of the Navy, are the institutions responsible for monitoring strict compliance with the prohibitions.

Castillo Novelo assured that, at least in his area, Campeche, shrimp farmers strictly comply with regulations and attribute the faults to the coastal fishery, although he recognizes that there is a lack of vigilance work on the part of government institutions.

“The ranger is overwhelmed by that system, they don't have the capacity and much less the personnel to do that type of surveillance, there is only one person here in the city of Campeche and he is the one who watches all the ships in the state of Campeche, which are like 100. Imagine in other states that there are more than 500,” he said in an interview.

Constant non-compliance with the ban

It doesn't happen once or twice, offenders are consistent. Companies or cooperatives whose boats go out fishing every month during the ban.

José Alfredo Munguia Fernández is one of the permit holders whose boats went out to sea on the most occasions during the closed season; his vessel was detected at 532 possible fishing spots during the period not allowed, between 2020 and 2021.

Munguia Fernández is a representative of the Union of Shipowners of the Pacific Ocean Coast and his fishing area is near Puerto Peñasco, in Sonora.

April, May, June, July, August, your Mezde boat never stopped during the restriction period.

The area is part of the Mexican Pacific maritime subregion Zone 1, the most affected in the entire country by non-compliance with the ban.

Jorge Francisco Mendoza Ramírez, the company SCP de Bienes y Serviços Guasave Cuatroentos, Miguel Ángel Galvez Martínez and Pesquera Meraz also operate there, others that have the most potential fishing spots closed.

Another of the permit holders with the highest possible fishing spots observed is Rodolfo Espinosa Gutiérrez, president of the Topo Viejo Union of Cooperative Societies and Shipowners.

The monitoring system identified fishing spots even in permanently closed areas, where trawling is not allowed.

An example is the case of the area of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean that extends from La Aguada Island, in Campeche, to the limits of Belize, with the exception of the fishing grounds of Contoy.

There, the Marengo and El Rey boats carried out activities. Both are owned by Sergio Candelario Rosado Pat.

Their boats were also detected during the closed season in the Contoy area.

The shrimp fishery is one of the strong pillars in the sector's economy.

According to the Mexican Fish and Seafood Consumption Perception Study, prepared by GlobeScan and the organization Collective Impact, shrimp is the favorite seafood in most Mexican cuisines, followed by tuna, salmon and tilapia.

In addition, Mexico exports more than 32,000 tons of shrimp, according to Sader data, with a production value of around 304 million dollars. Exports include shrimp farmed and caught in marshes and lagoons.

According to data from the Aquaculture and Fisheries Statistical Yearbook, updated to 2020, the offshore shrimp fishery reached 29,734 tons in the last year of registration.

According to statistics, this fishery has fallen over the past 5 years, while shrimp production in controlled cultivation increases every year.

The Pacific coast is the area with the highest shrimp production, in particular the states of Sinaloa and Sonora, followed by Tamaulipas, on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

Trawl fishing is an activity questioned by the environmental community. International organizations such as Greenpeace and Oceana have urged different governments to ban this activity, alleging serious damage to marine ecosystems.

Andres Beita-Jiménez, a researcher at the Fisheries and Marine Institute, Memorial University of Newfoundland, in Canada, said in an interview that it is possible to trawl in a sustainable way, but he considered that public policies to regulate it have failed in Latin America.

The Effects of Illegal Fishing

The prohibitions have a reason for being: to guarantee the biological cycle of shrimp, said Esteban García-Peña, director of fisheries campaigns for the organization Oceana.

The biologist also explained that these periods are usually established in recruitment seasons, that is, when shrimp individuals that spent their juvenile stage in mangrove areas are incorporated into the open sea.

In this period, he said, juveniles that do not yet reach adult size can be captured and, therefore, will not leave offspring.

García Peña identifies serious effects in two aspects, one economic-social and the other environmental.

The availability of the product for the next fishing period depends on respecting this reproduction cycle.

When it is done illegally, the employment of hundreds of workers and permit holders who did meet the established deadlines is put at risk, because since there is no good shrimp reproduction in the season, their economy will be impacted. Along the country's coastline, he said, entire families depend on this activity for their livelihood.

On the other hand, he pointed out, there is damage to ecosystems associated with non-compliance with closed periods in shrimp fishing.

The researcher stated that the profits of this fishery are not exclusively from catching shrimp, but also from incidental fishing, that is, those species that are trapped in trawls and that can be traded.

He indicated that audits carried out by Oceana in 2019 and 2021 identified that during periods of abundance, the catch is divided between 50% shrimp and 50% bycatch.

However, when it is scarce, it reaches 10% shrimp and 90% by-catch, he explained. This is one of the reasons why it is profitable to go fishing, even when shrimp is scarce on the high seas.

Incidental fishing, in his opinion, is poorly regulated in Mexico, because although the National Fishing Charter includes which species of by-catch can be commercialized and which cannot, there is no capacity to control the capture of species that are not allowed, such as beaked fish, stingray sharks or goldfish.

Shrimp farmers also become fishermen for scales, sharks, and other species, but without regulation, he added.

On the other hand, he pointed out that the decrease in fish stock due to not respecting the restrictions causes shrimp boats to increase their efforts in the established period, causing greater drag on the seabed, with the environmental consequences that this entails.

Lagoon ecosystems are also affected by interrupting the reproductive cycle.

As there are fewer reproductive individuals, because they were hunted the previous year, there will be fewer larvae in lagoons and wetlands, which impacts small species that rely on these larvae for their food.

“The entire food chain, which is very complex both in lagoon systems and in marine systems, is impacted. It breaks down the entire food chain and that affects not only the shrimp population but also the entire ecosystem,” he said.

Towards better practices

A sustainable fishery necessarily involves compliance with applicable regulations, said Francisco Vergara, head of Fisheries Dissemination in Mexico at the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), an international organization that sets a standard to ensure sustainability in this economic activity.

If bans are like a management tool, they have to comply with it, he added.

The specialist explained that one of the criteria of the MSC standard for obtaining a sustainability certification is the health of the fish stock and the management strategy. This criterion considers analysis, monitoring and capture control rules, as well as management measures.

In addition, the evaluation considers the existence of mechanisms to detect irregularities and punish non-compliance with regulations.

To obtain a certificate, the fishery must undergo a rigorous evaluation, carried out by auditors external to MSC.

The industrial shrimp fleet in the Pacific sought to obtain the sustainability label, but it stuck in the process.

In the public report, experts from the auditing team made specific comments on areas for improvement.

“There is evidence that the current management strategy has failed to maintain the level of exploitation of blue and white shrimp (...) There is no evidence that the corresponding sanctions are applied in all cases in case of non-compliance,” the document reads.

Researcher Andrés Beita-Jiménez said that although sustainability labels are an instrument of markets, as is the case of MSC certification, they are functional to pressure companies to comply with regulations and ensure the conservation of marine species.

Comentarios (0)