Sea cucumbers, in northwestern Mexico, are candidates for extinction. At the root of their critical situation is the lack of management programs and the illegal fishing that satisfies the appetite of the Asian market. Faced with the decline, the fishing communities of Baja California, which are economically dependent on this resource, hope to cultivate cucumbers to reduce pressure on wild individuals and repopulate overexploited areas.

Sea cucumbers (holoturoids) are a group of marine invertebrates that are related to stars and sea urchins. In Baja California, they are usually at a depth of between 60 and 80 meters under the sea. However, during the breeding season they come closer to the coasts and that is when they are most vulnerable to illegal fishing.

The risks of this species disappearing go beyond the loss of the sea cucumber itself and have implications for the entire ecosystem. When these animals feed, they move around the sea floor, cleaning the organic matter in the sand and preventing it from decomposing and contaminating the natural environment. In addition, when feeding, they remove and oxygenate the seabed.

For this reason, “when sea cucumbers are preyed upon, locusts, fish and corals die. Everything that inhabits the seabed dies because there is no one to clean and those areas become anoxic [without oxygen],” says Magali Zacarías, senior technician at the Ensenada Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education (Cicese).

Benjamín Barón is a senior researcher in the Cicese Department of Aquaculture and leader of the sea cucumber aquaculture project, which, after a year and a half of tests, is about to control the entire life cycle of the warty cucumber (Apostichopus parvimensis). The challenges, however, including technical and financial challenges, are many.

An adult specimen of warty sea cucumber in the Cicese. Source: Daniela Reyes.

An adult specimen of warty sea cucumber in the Cicese. Source: Daniela Reyes.

A History of Degradation

Sea cucumber is in high demand in the Asian market, where its consumption is a luxury reserved for special occasions. China, Hong Kong and South Korea are the main commercial destinations.

Its supposed medicinal properties and the fact that it is considered a culinary delicatessen in stews and soups, allow it to be sold at prices that, depending on the species, exceed one thousand dollars per dehydrated kilo.

Dried sea cucumber is the most commercialized and most valuable form, due to its long shelf life and ease of transport. When dried, a kilogram of sea cucumber turns into approximately 100 grams, which is why its price is so high.

In Asia, the development of technology has allowed the cultivation of the sea cucumber species Apostichopus japonicus, considered Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, demand is so high that this production is not enough to satisfy the market.

“They produce large quantities, but they also consume a lot of sea cucumber,” Zacarías says. In fact, “their production is not enough for them and that is why they have preyed on many of the species all over the planet,” he says. This was the case in Yucatán, in southeastern Mexico, where the sea cucumber of the species Isostichopus badionotus became such an important resource for the Asian market, that it ended up being overexploited and with a permanent ban that prohibits its capture since 2013.

In the quest to meet this demand, Mexico, and specifically the state of Baja California, play a key role, since, since 2021, it exports 100% of the sea cucumber that is produced.

The two commercial species of sea cucumber found off the coast of Baja California are the warty (Apostichopus parvimensis), which is found from the border with the United States to the middle of the Baja California peninsula, and the brown sea cucumber (Isostichopus fuscus), which is distributed from the Gulf of California to Peru.

Brown sea cucumber is classified as an Endangered species, both by the IUCN and by the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat), which is responsible for its management. Warty cucumbers are considered Vulnerable and do not have a management plan. It is only governed by annual catch quotas assigned by the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca).

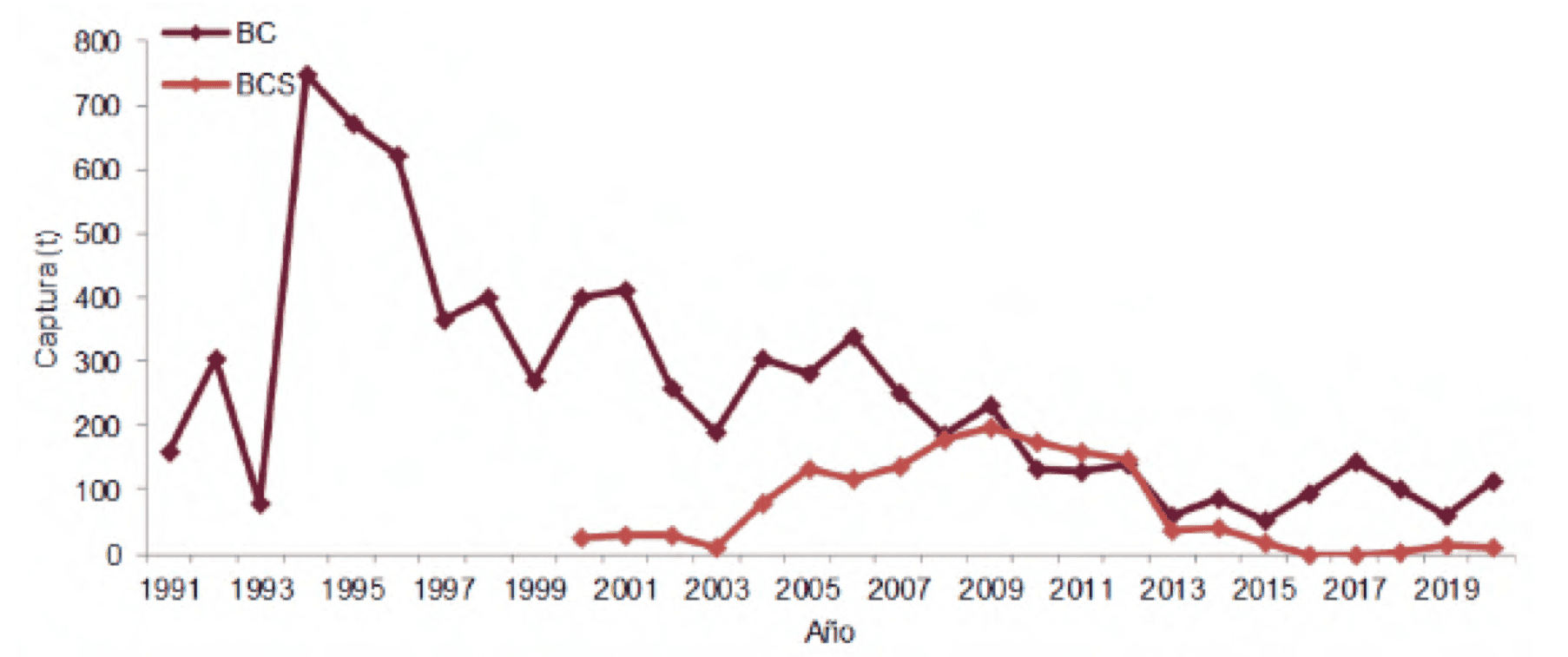

Sea cucumber production in northwestern Mexico: Source: National Fishing Charter (2023).

Sea cucumber production in northwestern Mexico: Source: National Fishing Charter (2023).

Since the production of warty cucumbers began to be recorded in 1991, maximum figures of up to 747 tons were reached in 1994. Since then, there has been a downward trend. In the period from 2013 to 2020, between 90 and 100 tons were caught annually, in accordance with the National Fisheries Charter.

In January 2021, the Center for Biological Diversity in Mexico, a non-profit conservation organization, submitted a request to Semarnat to consider the inclusion of warty sea cucumber in the list of threatened species listed in the Official Mexican Standard (NOM-059), but the request was not accepted.

The petition states that there has been a 50% reduction in the warty sea cucumber population in Baja California in the last three generations, covering an analysis period of approximately 12 to 15 years. It also indicates that in California, the United States, the reduction is 30% and that the average decrease over its entire distribution range ranges from 30% to 40%.

For Cathy Valdez, head of the Ensenada Regional Aquaculture and Fisheries Research Center (CRIAP), the incorporation of the species into NOM-059 should result in recovery, but support is required with inspection and surveillance. Enlisting it there would have a great impact on the economy of fishing communities, so it proposes a community recovery before including it in the standard.

“These are several factors, from ecological to management and also to fisheries. In the 90s, there was indiscriminate fishing for sea cucumbers and this led to a deterioration of wild populations and a lower availability of the resource. Also [there are problems] with the management that has been given to it and unregulated, unregistered fishing or illegal fishing also play a large part in this decline,” Valdez points out.

These factors, combined with the effects of climate change on the sea and high market demand, are diminishing sea cucumber populations and destroying their habitat, according to Carolina Navarrete, biologist and head of benthic products at CRIAP Ensenada.

In 2018, the National Fishing Charter showed that warty sea cucumber was “used to the maximum sustainable” and recommended not increasing fishing effort for commercial use, which at that time numbered 26 permits and 164 boats, of which 100 were in Baja California.

However, this first recommendation was ignored and by 2023 the fishing effort amounted to 31 permits and 272 authorized vessels, of which 178 correspond to Baja California, according to Valdez.

Cultivate hope

Pond area for the cultivation of brown sea cucumber in the facilities of the Cicese Ensenada. Source: Daniela Reyes.

Pond area for the cultivation of brown sea cucumber in the facilities of the Cicese Ensenada. Source: Daniela Reyes.

The first attempts to cultivate sea cucumbers in Mexico were in 2009. The Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute in Yucatán began experimenting with cucumber species from southeastern Mexico: chocolate chips (Isostichopus badionotus) and pencil cucumber (Holothuria floridana). In 2024, Cicese began the first investigations for the cultivation of brown and verrugoso sea cucumbers, species from the Gulf of California and the Pacific Ocean, respectively.

“We conceive aquaculture as an auxiliary tool to contain the deterioration of species because it has several possible solutions: one is to produce to market, but another is to produce to repopulation. These are the two very important aspects of aquaculture, and cucumbers are a highly threatened species,” says Barón.

The Cicese project received funding from the National Council for Science and Technology (Conacyt) for three years starting in 2024 to start a project to reproduce brown cucumbers. However, one of the biggest obstacles has been obtaining specimens of this species, since being protected, permits are required, which are difficult to obtain.

In November 2024, through a permit grant, scientists obtained 57 specimens of brown sea cucumber that are currently in the laboratory. The group of researchers made up of Barón, Zacarías and Beatriz Cordero has tried to obtain authorization from Conapesca to extract 50 specimens of this species annually without the need to go through an intermediary with a fishing permit, but they have not been successful.

“One way to take care of a species that is in an ecological problem is to promote aquaculture and we assumed it would be simple, but we have been faced with the fact that the authority does not discriminate to regulate. For them, a research center is the same as a fishing organization, so it requires too much of us and it has become very difficult for us to obtain brown cucumber specimens to work with,” says Barón.

Mongabay Latam, following the Conapesca protocol, requested an interview with the organization, but it has not been finalized until the publication of this note.

Researchers are currently studying the biology of brown cucumbers and have already started researching warty cucumbers, thanks to the fact that they were able to obtain specimens through the cooperative Buzos y Pescadores del Ejido Coronel Esteban Cantú. Diets are being tested for both species and looking for the right physico-chemical parameters for their cultivation.

Laboratory experimentation involves the risk that any change in diet, in water temperature, in lighting, failures in pumping water or the presence of parasites or other organisms can kill all the specimens, as happened with a batch of juveniles of warty cucumbers reproduced in the laboratory.

“We must be very careful with them because we know that we are not going to have more animals in the rest of the year,” Zacarías says.

They had a batch of 106 specimens of warty cucumbers and had managed to keep them stable for a year. They even worked their entire life cycle successfully, from adulthood, reproduction and the first days of juvenile life, which they have not achieved with brown sea cucumber.

However, after reproduction, a copepod, a small carnivorous crustacean, filtered through the seawater that the Cicese pumps from Ensenada Bay to fill the ponds. In one weekend, this crustacean killed thousands of larvae and juveniles, in addition to the microalgae that are the food of sea cucumbers at that stage.

Such situations are common during research and experimentation, experts say. These processes require a lot of time, attention and money, since they involve a team of specialists to meet all the needs of the crop, from food, technology, physiology and pathologies.

The objective of the project is to control the cultivation process of brown and warty sea cucumber in a laboratory and, subsequently, to supply juveniles to fishing cooperatives that already have catch permits so that they can continue raising the organisms in maricultural conditions up to their commercial size.

“We want to domesticate the species and that involves total domination of its life cycle. That they get used to driving under total human control. This is the most complex challenge because it involves adapting or knowing many of the environmental characteristics that allow you to maintain them in the long term,” says Barón.

In addition, the cultivation of sea cucumber would guarantee product traceability that is difficult to achieve with wild fishing in the current context, explains Valdez.

Until now, no project has reached the point of producing seeds for repopulation. Coupled with the lack of funding to increase capacity in laboratories, the legal complications of obtaining specimens of brown sea cucumber, and the long life cycle of cucumbers, research to master them is progressing slowly. However, expectations are high.

In the future, juveniles could be used by cooperatives for aquaculture or by the government for repopulation, but what Barón is certain of is that this technology will reduce the pressure that currently exists on sea cucumbers.

“Probably, the simple fact of aquaculture lowers pressure on fish resources and that could be a partial solution to the problem without the need for repopulation, which is very expensive. This model, and much of what we have done in the field of aquaculture, has its origin in academia, but the idea is that it then permeates society in public, private or social entities,” says the researcher.

Impact of illegality on communities

Above: photograph of Ejido Coronel Esteban Cantú. Below: Photograph of La Bufadora that is located near the area where sea cucumbers are caught. Source: Daniela Reyes.

Above: photograph of Ejido Coronel Esteban Cantú. Below: Photograph of La Bufadora that is located near the area where sea cucumbers are caught. Source: Daniela Reyes.

23 kilometers from the port of Ensenada is the cooperative Divers and Fishermen of the Ejido Coronel Esteban Cantú, which relies on sea urchin fishing and relies on sea cucumbers during the closed period.

The 39 members go out to the rough waters of Arbolitos Beach, about seven kilometers from the ejido, very close to the marine geyser known as La Bufadora, to obtain the support of their families.

Until a few years ago, the cooperative carried out surveillance tours to deter illegal fishing, but they stopped doing so because of the high risk involved.

“Since the cooperative was founded, there has been an agreement to take care of the area. Before, we were very angry. We took care 24 hours a day because there were a lot of pirates. We would surprise a boat, we would tie it up, we would tow it, we would talk to the inspectors of Conapesca or the Secretariat of the Navy and they would take care of it. Currently that no longer works, the conditions have changed,” says a member of the cooperative who chose not to identify himself for fear of reprisals. “It's dangerous to approach the boats and we'd better leave them because safety is at risk,” he says.

As a result of the presence of illegal fishermen, they have lost power and governance in their own territory. In addition, given the fear and lack of results on the part of Conapesca, they have stopped reporting.

Until 2023, Conapesca had three boats and 10 land vehicles for inspection and surveillance tasks throughout Baja California. In addition to 17 Federal Fisheries Officers attached to the Directorate of Inspection and Surveillance.

During 2024, Conapesca had the lowest operating budget since 2016 to date, with 74 million 584 thousand pesos (approximately 4 million dollars) for inspection and surveillance tasks throughout the country.

The cooperative perceives that the authorities have lost their presence in the territory and that has been a factor that has contributed to its crisis.

“The resource is in decline because it is overexploited. Right now it's a mess and you're demoralizing,” says a member of the cooperative.

Playa Los Arbolitos where fishermen from the Buzos cooperative and fishermen from Ejido Coronel Esteban Cantú moor and drown. Source: Daniela Reyes.

Playa Los Arbolitos where fishermen from the Buzos cooperative and fishermen from Ejido Coronel Esteban Cantú moor and drown. Source: Daniela Reyes.

Although they do not have a favorable scenario, the cooperative remains optimistic and cooperates with projects, such as the cultivation of sea cucumbers, which represents hope to continue dedicating itself to fishing.

“There are cooperative members who tell me to sell everything and distribute the money, but I tell them no, that this is not over yet,” says the member of the cooperative who preferred to remain anonymous for safety. For him, there is still hope. “A change can be made, but we need to have the will to do it, for the good of all, because if there is no business here with fishing, everything ends.”

*This report was selected by the Mongabay Latam grant to tell stories about oceans.

Comentarios (0)