The oasis of the town of Todos Santos in northwestern Mexico is a space of high value for the local community, however, for five years it has been in a process of accelerated deterioration due to the tourist and agricultural real estate sector. In its defense, the community proposes to create a public park.

From the upper part of the town you can see a shoal full of palm trees and some orchards parallel to a body of water that flows into La Poza, a coastal lagoon. The landscape is called El Valle del Pilar, in honor of the Virgen del Pilar, who is the town's patron saint, but also El Palmar, recently designated by the academy as an oasis.

Palm grove and orchard area in Todos Santos. Source: Daniela Reyes

Palm grove and orchard area in Todos Santos. Source: Daniela Reyes

Baja California Sur is the driest state in Mexico and the only one with oases, which represent less than 1% of the state's total area. Oases are ecological systems composed of a body of water and areas of vegetation installed in arid zones created to facilitate agriculture in the desert.

“The oasis allowed regional sustainability in an environment of water scarcity and has a very important social factor composed of traditional entities and practitioners who were responsible for evenly distributing resources to ensure the well-being of all in an environment characterized by isolation and aridity,” said Teresa Egea, sustainability consultant and landscape designer.

The Todos Santos oasis is one of the most important wetlands in the state but, according to a study by the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) published in 2020, it is in a process of deterioration due to tourism, agriculture and extreme natural events.

“The South California archipelago of oases is interconnected. It is a system along the entire Baja California peninsula. Todos Santos is the second oasis with the highest agro-biodiversity of all the archipelagoes. In addition, it is the most eroded oasis and most endangered,” said Egea.

The study showed with satellite images that the extension of the oasis decreased by 51.2% in 17 years (from 2002 to 2019), while the La Poza lagoon decreased by 63% and the natural landscape by 21.7%.

In that same period, agricultural land use increased by 86.59% and urban land use by 43.57%, as can be seen in the comparative map where, as urban growth increases, the vegetation cover of the oasis decreases and the extension of La Poza decreases.

The sidewalks of the water: Public Park Proposal

As a sustainability consultant, Egea came to live in Todos Santos in 2017. She studied the oasis and integrated it into the designs for which she was hired. However, the developers did not understand the importance of the oasis and, instead of keeping it, they sought to erase it with their projects.

“I get tired of having to deal with advice and proposals to developers and foreign people who hire me with objectives of integration and commitment to the community, but who don't understand my advice because they are not integrated and because their priorities are really different. They have this tendency to arrive and erase all history, and to segregate the local population, which is increasingly being displaced from privileged and historic places to places without resources,” said Egea.

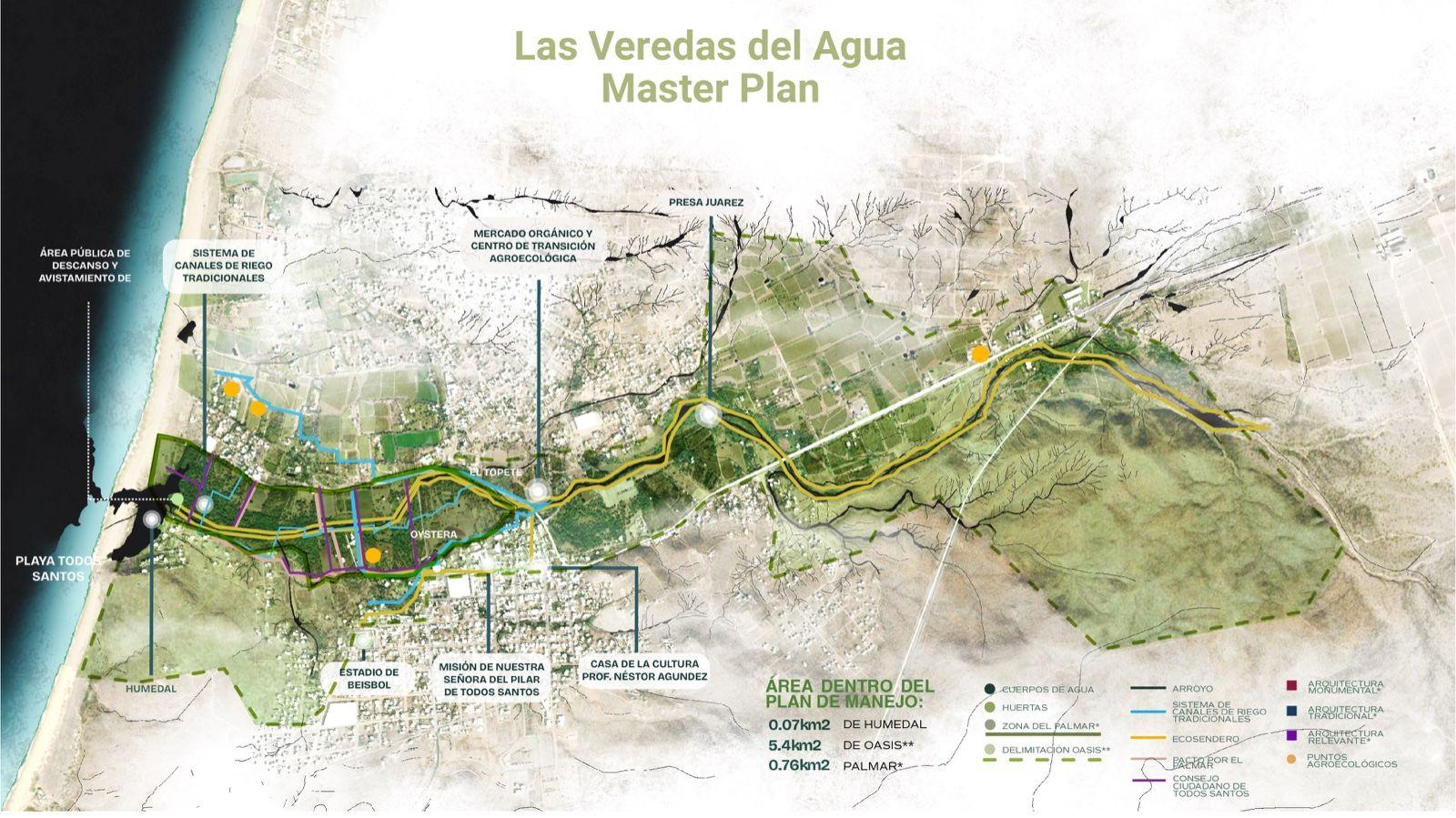

Based on his experience, he decided to undertake a proposal for a solution: a land planning plan that focuses on cultural identity, historical memory and natural resources, embodied in the project Las Veredas del Agua.

The project proposes to conserve the area of the oasis, which is 5.2 square kilometers, and rehabilitate it as a public park. It includes an ecopath that runs through it and reconnects the key elements of the territory to encourage people to walk the water paths of the oasis again.

“Walking through the territory, the population is once again aware of the place, which is key to understanding history and culture. Connections are created between different local populations that are very disconnected,” said Egea.

The project considers it crucial to create a public market where you can sell what is produced in local gardens, to push a transition from industrial agriculture to a traditional one with local value.

The idea of creating a public park in the oasis had been around for some time among the population, but Egea founded it through interviews and research. This is how he created a first conceptual proposal that received an honorable mention in the territorial planning category at the Latin American Biennial of Landscape Architecture 2024.

Currently, the project is in the phase of building partnerships at the local level to create the technical design of the project in a participatory way.

“The ideal is to create local governance with all sectors. Civil society designs, companies provide financial support, academia guides the process and the government approves. You can't do it without one of these actors,” said Egea.

In partnership with the organization Protect All Saints, on June 20 and 21, the project will be presented at a public event to the community where, through work tables, it can be part of its design.

Demonstration against Cabo Santos and The Palmoral real estate and tourism projects in Todos Santos on May 3, 2025. Source: Daniela Reyes and Peskydrone.

Demonstration against Cabo Santos and The Palmoral real estate and tourism projects in Todos Santos on May 3, 2025. Source: Daniela Reyes and Peskydrone.

Proposals such as the public park have gained relevance among the resident population after two megaprojects for tourism and real estate were made public near and in the oasis: The Palmoral by Santa Terra and Cabo Santos, which the community has opposed through demonstrations and the collection of signatures.

Urban growth and, in particular, these types of projects compromise the aquifer that supplies the resident community and that feeds the oasis, said Diego Ramírez, director of Protecting Todos Santos.

“The problem with the increase in population density is precisely that the water extracted for domestic, commercial and agricultural supply is removed from the Todos Santos aquifer and that aquifer is precisely where the oasis is located. Its deterioration is largely due to water piping. Many of the trees start to dry out because they no longer receive water, which now goes inside a tube,” Ramírez said.

The UABCS study defined the Todos Santos Oasis aquifer as overexploited due to reduced water levels and increased salinity near the coast.

In the past, springs flowed continuously throughout the year, but since 2007 the flow has been limited most of the year, with the exception of short periods of tropical cyclones, according to the UABCS study.

Old image of the Todos Santos oasis. Source: Pablo L. Martínez Historical Archive

Old image of the Todos Santos oasis. Source: Pablo L. Martínez Historical Archive

For Ramírez, urban growth for high-density projects has transformed what was a historic landscape, created for food production, into a privileged place used for real estate speculation.

This is reflected, for example, in the town's Subregional Urban Development Program, where, in the last update it had, it changed from palm groves and orchards to landscape use.

“The word implies a lot of things because it now has a connotation more focused on tourism, unlike palmares and orchards whose definition was to produce food, so it also loses its essence and now becomes a concept more symbolically attached to tourism development,” Ramírez said.

In the past, people from all over the world came to the oasis to swim, do clothes, play, party, so it had a high social value that has been lost. Currently, most of the orchards have been lost and little by little private property has been closing access to the stream that runs in the oasis.

“The park would be like a way to reuse those spaces, and as a way to also protect it, because it would no longer be abandoned,” Ramírez said.

When the Jesuits arrived in Baja California Sur, they changed the landscape by creating these oases around the missions, but that meant the displacement and extinction of the original peoples. Ramírez fears that if the landscape that has allowed survival for so long in an arid region is changed again, this time it will entail the extinction of traditional knowledge and cultural heritage.

“We have very little time with the imminent threats of developments. That biological and socio-environmental corridor that constitutes the oasis, they want to turn it into a tourist corridor. This moment is key to avoid seeing before our eyes a place that is a world heritage site transformed into a tourist corridor in which little by little the oasis will disappear completely,” said Egea.

Comentarios (0)