The beach. If Lourdes Magaña, a merchant from Mérida, Yucatán, is asked about her happiest childhood memories, that's her automatic answer. The enormous stretch of white sand where he sat waiting for sunsets in summer and played volleyball or softball with his sisters and brothers.

At the end of 1970, his family, despite having few financial resources, managed to rent a house near 12th Street in Chicxulub, a community belonging to the coastal municipality of Progreso, in this state in southeastern Mexico, to spend their summer holidays.

“We were just going home to sleep. We woke up early to go to the beach to watch the sunrise. I would play for hours in the sand, make the little house I dreamed of, let my imagination run wild. That's where I learned to swim. I didn't use sunscreen and to date my nose is peeled, as if with scars. But I didn't care. We spent the whole afternoon-night there,” she says nostalgically.

This year he returned to the happiest place of his childhood, but he couldn't rescue his memories. There is no longer a beach. The sea hits the houses directly. “The change is brutal,” he adds.

You might think that everything is the result of Lourdes's perception, but that's not the case. The beach where 12th Street flows, located east of the Chicxulub pier, is one of the red spots of coastal erosion in Yucatán: it went from having 14 meters of sand in 2006, to only four meters in 2023, according to Jorge Euán, professor at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Polytechnic Institute (Cinvestav).

None of the specialists, fishermen or vacationers consulted by Causa Natura Media for this report knows with certainty when it began, but they all agree that in the last 40 years the sea has “eaten” the beaches of the north coast of Yucatan, and that this problem does not only cause material damage: it also threatens biodiversity and the social fabric of the state. In addition, they agree that they have seen several proposals to solve the problem, but not results.

A natural phenomenon became a problem

Although it may not seem like it, the beach is a fragile and “unstable” ecosystem, since it combines the cycles of tides, sea currents and sediments, such as sand. One of these cycles is erosion-deposition, which can be annual or semi-annual: normally, beaches wear out during winters or in seasons of storms and hurricanes, because northerly rains and winds, as well as strong and short waves, carry the sediments out to sea.

But in summer or in times of calm, when the waves are smaller and break with longer frequencies, the sand returns from the bottom of the sea, allowing the beach to recover. This process can be fast or slow, depending on the strength of the meteorological phenomena that have impacted the area.

In the case of Yucatecan beaches, the sediments arrive from the east side to the west, according to the head of Cinvestav's Department of Marine Resources, Alejandro Souza.

However, in the last four decades, sand has not returned to certain parts of the Yucatan coast: the beaches have only worn out. And although natural factors such as climate change influence this fact, the truth is that human actions are what are preventing this natural process from happening.

The red lights

Some studies indicate that, on average, 19 meters of beach were lost throughout the Yucatan Peninsula from 1980 to 2019. In 2007, Cinvestav studied how the entity's shorelines were located and found that in 27% of the entire coastal strip there were houses separated by less than 10 meters from the sea.

The Report Card for the Yucatecan Coast, prepared by the National Laboratory of Coastal Resilience (Lanresc), in 2017, specifies that the stretch from the municipality of Dzilam de Bravo to that of Hunucmán is in poor condition in terms of coastal erosion, specifically, the beaches of Telchac and Progreso.

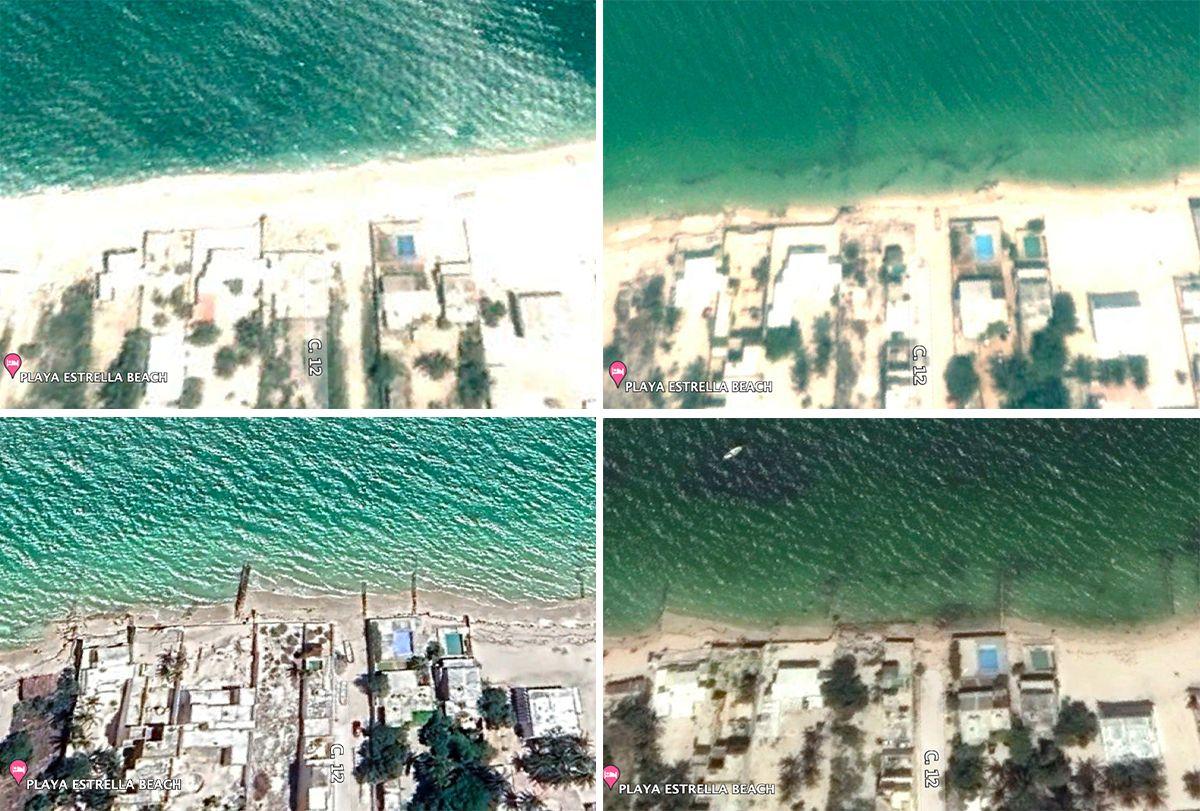

This is confirmed by specialists from Cinvestav, the Sisal Academic Unit of Unam and Uady, who analyzed satellite images captured over different years with tools such as Google Earth, to compare the extensions of the beaches and measure the advance of the sea.

Thus, they detected “red spots” of erosion within the coastal strip, which is in worse conditions.

For example, Cinvestav professor Jorge Euán identified setbacks of up to six meters per year at several points in Telchac. It also considers the three coastal police stations in Progreso: Chelem, Chuburná and Chicxulub as red lights. The first has generated concern, since various measures have been implemented there to combat erosion without bearing any fruit.

This is the case of 12th Street, which was riddled with breakwaters that were not effective. In 2005, that area no longer had any sediment, so the structures were removed and a sand filling of between 10 and 12 meters was made. But the remedy only lasted 5 years: since 2011 the site has not had a beach again.

Chicxulub is another critical point for Euán, who specifically pointed out the place where Lourdes Magaña built her happy childhood memories: 12th Street, which lost half a meter a year.

Chuburná is also considered a critical area. Estimates by researcher Alec Torres, from the Sisal Academic Unit, indicate that in Laguna de la Carbonera the retreat is approximately six meters per year.

Although, in Yucatán, the entire coastline has a similar profile: waves and currents are constant on all beaches, not all of them are eroded.

How did we come to this?

Some researchers, such as Torres and Souza, point to the expansion of the Pier, carried out at the end of 1980, as one of the causes of erosion on the northern coast of Yucatán, since the intervention was not properly planned and modified the waves in the area.

Another is the shelters (the places where boats are kept): academics indicate that in Yucatán they were built by digging in the wetlands of the swamps and to connect them to the sea, entrances were opened that, naturally, were filled with sand.

To avoid this, breakwaters were installed, some walls made of sticks and stones, which stop sedimentary transport. Since the sand in the state moves from east to west, the breakwaters led to the formation of plateaus on the east side of the shelters, and, by preventing the flow of the sediment, they eroded the beaches located in the western area.

Another crucial factor are spurs, geotubes and other temporary “remedies”, which, according to Appendini, had their “boom” in the late 80s, when faced with the first glimpses of erosion on the north coast, people who owned oceanfront homes panicked and began to take improvised measures to mitigate erosion on their land, without knowing that this was aggravating the problem.

The above-mentioned structures serve to hold sand, so they are usually effective in maintaining the beach. But that means interrupting the flow of sediment on the coast. And the remedy becomes the disease.

“They saw that they stopped the erosion a little. Then everything was filled with spurs. Lonely people created an erosion problem, because you put one on and within 24 hours it erodes you downstream. This happens when people perceive a danger and take actions that have no engineering basis. I have seen cases where people place spurs to protect themselves, but they do it in the wrong place and end up increasing the erosion of their own land,” said the academic.

Currently, to carry out any type of intervention at sea, permits are required from the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat). However, an alarming number of such works installed without authorization have been detected. Despite that, less than half have been withdrawn.

The lack of planning and the housing boom are considered primary causes of the serious problem of erosion, since evidence indicates that right where the beaches are most worn out is where all the condominiums and summer houses are built.

Construction regulations on the coast are relatively new. In fact, it was in July 2007 that the Ecological Management Program for the Coastal Territory of the State of Yucatán (Poetcy) was enacted, which was reformed in 2014.

Thanks to this regulation, it is now forbidden to build buildings less than 20 meters from the mangrove forest or less than 40 meters from a body of water. Nor can it be built on the first dune, nor can it destroy the creeping vegetation that characterizes it.

In addition, an Environmental Impact Statement (MIA) is required, prior to any type of work, and depending on the size of the land, location and land use, it is requested to conserve a percentage of the unbuilt area.

However, 60 years ago the picture was not the same. In the “desire to be in front of the sea”, citizens built on the dune, and to build fences or pools they removed the creeping vegetation that characterizes it, which in addition to cushioning floods, protecting the coast from waves and winds and being home to different animal species, has the function of retaining and fixing sand, Brito explained.

“If people don't respect the natural system, there are consequences,” said Appendini, who added that straight accesses to the beach have also begun to be built, which favors flooding.

Unfortunately, it's not all due to past actions. Both Appendini and Brito said that to date, cases of non-compliance with the Poetcy parameters continue to be detected, affecting the first dune, mangroves, bodies of water, coastal flora or fauna.

The UNAM academic has detected cases of large complexes built on the seafront, and he did not rule out that there are corruption networks that allow works to be carried out that do not have the corresponding permits

Another cause of erosion is global warming, which not only affects the melting of glaciers and rising sea levels, but also generates stronger storms and hurricanes, causing more aggressive winds and waves, which wear out the beach frequently, without giving it time to recover.

One factor that has not been analyzed in depth, but could be linked to the scarcity of sand is the possibility that sedimentation sources are depleted, according to Dr. Euán.

The failures of the fight against erosion

The midday sun hits harder than usual in Chicxulub. Although it's not high season, a handful of families are tourists at that Buenos Aires police station in Progreso. Some take refuge in restaurants. Others, such as Alberto Nahuat's, are going to explore the sea. But they discover that they don't just have to avoid the sun's rays: they also have to juggle to find a piece of sand where they can rest.

After searching for a while, they succeed: they settle in the few centimeters of space they find between the wall of a house and the waves. In the stones that surround them, they place a refrigerator and they prepare to look at the landscape.

“I know that this erosion thing is a thing of nature, but the government must take measures to prevent it,” he says in an interview.

State authorities say they have implemented various measures to prevent beach erosion from worsening.

Starting with the 2020 Expenditure Budget, a component of “recovered eroded coastal areas” began to be specifically identified, which includes the development of the coastal management program for the conservation and improvement of eroded areas, carrying out actions for the restoration of sand transport in coastal dynamics and the coordination of beach and mangrove cleaning. But that doesn't necessarily represent progress.

According to the results-based Budget documents, provided by the Secretariat of Administration and Finance (SAF) through the National Transparency Platform (PNT), in 2018 and 2019, actions related to coastal erosion were included, along with others, in the Program for Adaptation to Extreme Weather Events, to which a total of 10 million 533 thousand 428 pesos and 21 million 227 thousand 159 pesos were allocated per year, respectively.

In 2020, the erosion component was specifically added to the Program for Conservation and Integrated Management of the Coastal Zone, which received 11 million 177 thousand 448 pesos; but resources fell 96% in 2021, when 397 thousand pesos were allocated to it. And in 2022, it was only 347,000 pesos.

For the 2023 budget, the component referring to recovered eroded coastal areas was included in the Priority Ecosystem Conservation Program, to which 674,044 pesos were allocated.

That didn't mean that more money was allocated to strategies to prevent beach wear and tear or rescue them. Through the PNT, the entity's Secretariat for Sustainable Development (SDS) specified that in 2018 no resources were granted for that purpose due to administrative change. In 2019, 35,858 pesos were allocated; in 2020, only 4,000 pesos, and from 2021 to 2023, there were 40,000 pesos.

In other words, concrete actions to combat erosion have accounted for less than 12% of the resources allocated to coastal management programs.

Failed answers

Emphasis is placed on resources because another point, on which specialists agree, is that effective solutions to this problem are expensive: none are immediate, they require previous studies and their operation is long-term, therefore, not only should we consider installation costs of structures or machinery, but also of maintenance.

In addition, for such actions to really work, they must be thought, designed and implemented “globally”, that is, taking into account the coast as the complex system that it is, and not limiting the measures to a single piece of the beach.

For example, several buttons: in 2014, the administration headed by PRI member Rolando Zapata filled seven kilometers of sand between Chicxulub and Yucalpetén, but it only worked during the months of July and August.

The failure of this measure caused discomfort among residents who already had the sea just a step away from their patios. In response, in 2016 they formed the group “United for the Beaches”, and in October of that year they signed an agreement in which the Yucatan government committed itself to carrying out studies on erosion and partially solving the problem.

In 2017, the collective, on the recommendation of the UNAM, began to remove illegal spurs. But two years later he installed geotextiles, which do not solve the problem either and can generate others.

“No one is responsible. If they don't work, nobody takes them away, they stay half buried in the sand, they break and they stay there contaminating the beach and posing a risk,” Appendini said.

In 2019, the state government, under the leadership of the panist Mauricio Vila Dosal, installed two bypasses, structures that extract sand from accumulation areas and deposit it in erosion areas.

One of the works was built in the shelter port of Chuburná and the other in that of Telchac, both were operated together with the Secretariat of the Navy (Semar). As announced, more than 14 million pesos were invested.

Although researchers agree that bypasses are an effective way to solve both sand piles at the entrance of shelters and coastal erosion, and they even mention that all shelters should have one to compensate for the impact on the sediment transport cycle on the coast, they also agree that sand pumping requires constant maintenance and vigilance, something that has been lacking in the two that are located on the Yucatecan coast.

In 2020, under the argument of the health contingency due to the Covid-19 pandemic, both facilities stopped working. At the time, the Secretary of Sustainable Development, Sayda Rodríguez, assured that as soon as the health emergency passed, operations would resume, but the truth is that both academics, residents and fishermen do not know what happened to those systems.

Causa Natura Media went to the two points where the bypasses were installed. In the shelter port of Telchac, fixed and floating hoses and pipes were dismantled, and machinery was carrying out dredging work. At the site, it was discovered that the bypass has been discontinued since last year, and now part of the pipe is used to move the sand removed from the dredge to the west coast.

Appendini, who participated in the UNAM team that collaborated in the installation of this bypass, stated that the system was not properly implemented.

“We proposed a bypass and in the end it couldn't be done that way. And that's okay, you can't always do things as planned, but then I visited the place and saw that it wasn't running properly: if you throw the sand too close, it won't catch the coastal current and you can stay there. You have to take the sand farther away, to where there is the coastal current that can carry it. Why didn't they? Because it's much more expensive to install hoses up to that point,” the specialist acknowledged.

In Chuburná, the fate of the bypass was not known either. When consulting them on the subject, the members of the Chuburná Nautical Committee stated that no authority explained or consulted anything about the project, which was harmful to them, since none of the specialists who arrived considered their knowledge of the currents and fauna of the area.

“They threw the sand on the west side. And we said no, because all the time we have the chik'in iik', the wind from the west. That wind brings the sand back to the beach, because that's the way the current goes. We talked to the biologists and they said they had studies. They do have studies, but they don't live it, we live it and we know what wind affects us,” said Samuel Caamal, treasurer of the group.

In the same way, the fishermen detected a reef on the west side of the breakwater and warned the people responsible that sand deposits could affect it. But they didn't listen to them.

“There were products of all kinds there, such as octopus. But it was worth a cricket for them. And they buried him,” said Daniel Pool, president of the Chuburná Nautical Committee.

What if the beaches are lost?

Beyond the damage to the homes of wealthy families, whose construction was partly the cause of the problem, coastal erosion can cause significant damage to the ecosystem.

One of the most serious is the salinization of fresh water. According to Torres, as the coastline advances, so will marine waters and, therefore, there will be a tendency to salinize any well, especially in areas close to the coast.

In the same way, the hydrodynamics and water quality of this area covered by mangroves, which are a “nursery” for different animal species, can be modified.

Wildlife is also damaged and among the main victims are white turtles and hawksbills, the two species that nest most frequently in the state, which are on the Red List and are currently protected by the Official Mexican Standard (NOM) 059.

The fact is that, according to the coordinator of the turtle camp of the Center for Technological Studies of the Sea (CETMar) in Progreso, the turtles return to the beaches where they were born to spawn.

However, some of these areas no longer exist: they are already under water or are littered with geotubes and spurs. This prevents nesting and is a risk, because if turtles don't spawn they can die.

Those who manage to find some piece of sand face other problems: having a very small space of sand between houses and the sea, they tend to make surface nests, which exposes eggs to both water and sun and to animal or human predators. And being close to homes, turtles are vulnerable to attacks from other animals, such as feral dogs.

On the other hand, when some turtles can't find a beach, they enter the patios of summer homes, where they can harm themselves with structures such as pools or high-rise retaining walls, all without counting the possibility of being abused.

In the last year alone, Carlos has dealt with two reports of turtles falling into swimming pools, three of exposure of nests and four of feral dog attacks in Progreso.

Unfortunately, turtles aren't the only ones affected. The beaches are also resting areas for seabirds and there are organisms that live in the sediment, such as those called “wéech” (which means “armadillo” in Mayan), and that are a species of insects that lived in the sand, specified Dr. Euán.

Another effect, which in turn was one of the causes, is the destruction of the dune and the loss of vegetation. Without dune, there is no creeping flora. Without that vegetation, there is no way to fix the sand. And the coast is exposed to strong winds and waves.

Erosion has also impacted fishermen, who used to guard their boats on beaches and must now take other measures. There is no count of how many houses have collapsed due to the effects of the tides, or how many already have the sea practically in the yard.

What is known is that this heritage is in uncertainty, because according to Mexican laws, the 20 meters from where the waves break inland are part of the Federal Maritime Terrestrial Zone (Zofemat). In other words, technically, the properties affected by erosion are in federal territory.

“If federal authorities took legal action, those properties where the waves are already breaking would no longer be private property, but the property of the Nation. We assume that the Federal Government has not intervened because there are too many houses in that situation in Yucatán, and surely thousands of amparos would be detonated to protect the heritage,” Luis Brito explained.

The solution in limbo

Will the beaches that have already been lost ever recover? Can other areas be prevented from being eaten by the sea?

Experts say yes, but they are not very optimistic because of the economic and social costs of effective measures to combat the problem. They emphasized that no short-term measure, designed for a single area, that does not have the right equipment and personnel to manage it, will work.

One of the ideas considered is the redesign of shelters, with structures that allow the transport of sediments, and with the commitment to so-called “soft engineering”: new technologies developed with plants, such as seagrass or creeping dune vegetation.

Another was the creation of artificial dunes or the regeneration of the beach-dune system, either through the demolition of houses that already have irreparable damage or through a filling of sand, so that vegetation can be planted and the entire system can be reproduced.

But in order to fulfill those dreams, experts recommended eliminating structures that prevent the natural transport of sediment, carrying out global studies of Yucatecan coastal dynamics and reforming construction regulations on the coast (the Poetcy), to prevent construction in vulnerable areas prone to erosion and flooding.

Euán also suggested that linear accesses to the beach should no longer be allowed to be built, but that they should all be diagonal or “shaped like that”, so as not to promote water transit and erosion.

For his part, Brito recommended that in areas close to the sea, only stilt houses be approved, those raised and not at floor level, to respect the vegetation of the dune and allow the flow of sand and water.

A few were more drastic, and stressed that it is necessary to ban construction on the coastal strip. Like Appendini, who reiterated the fragility and importance of the beach ecosystem.

“When we're little kids, we build castles in the sand and if they fall, nothing happens, because we know that's going to happen. Building a house on the beach is the same thing. We must be aware of that. We must respect the natural system and build according to nature. Now there's a lot of talk about nature-based solutions, but before we get to that, we should build with nature,” he said.

Comentarios (0)