Illustration: Esteban Silma.

North of Iztapalapa, in Mexico City, fish and seafood from all over the country arrive at the Nueva Viga market. Between the coming and going of the vendors and the pungent smell of the fish, inspectors from the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Commission (Conapesca) carry out rounds to verify what is coming in and what is being sold.

This morning, at the entrance to the market, two inspectors stop a white Toyota van. The driver introduces himself and agrees to show the mandatory documentation: an invoice issued by a fishing cooperative in Cárdenas, Tabasco, and a fishing guide with which he covers 200 kilos of farts, 160 kilos of saws, 155 of snapper, 210 of huachinango and 220 kilos of sea bream.

— What do you transport? — asks one of the fishing officers.

— Fishery product. I go to warehouse 18 of platform “A” and 25 of platform “D"— answers the driver.

However, there is a problem. Of the total kilos transported, there are 50 kilos of dogfish and 100 kilos of rabbit fish that are not accredited by an invoice.

“They (the driver) are told that without the invoice they cannot prove the legal origin of the fishing product and an inspection report will be drawn up and the fishing product will be retained as a precautionary measure... as well as the vehicle,” says one of the Conapesca officials.

What happened next, according to the resolution of file 100.2C.21/PA/CDMX/089/2022, is that it was not possible to prove the documentation of the 100 kilos of rabbit fish retained. The process ended with a fine of more than 96,000 pesos in which it is unknown if the driver was able to resolve the debt. The last thing that is reported is that during the legal process they visited him at his home in Tabasco and he was not located, they said that he no longer lived there.

Transporting fish and seafood without documents is one of the main forms of illegal fishing. The inability to verify the origin and destination represents not knowing if the product was caught in a protected area, during the closed season or without permission.

In the Nueva Viga market, the largest of its kind in Mexico and the second in the world, finding these cases is a task on the shoulders of two inspectors, rotated in shifts. The quantity of merchandise exceeds its capacity, a thousand tons are sold daily in that market.

What size is the problem?

A sanction for a fishing offender is only possible if they are first identified.

An analysis carried out by Causa Natura Media on 288 inspection and surveillance records made public by Conapesca reveals that 26.3% of the total had an identified person.

However, punishing a person identified for having committed fishing offences goes a long way, where defendants have the possibility of presenting evidence to avoid a sanction, said several people related to the work of Conapesca.

These allegations of those mentioned above serve, for example, to demonstrate that you have a permit, the legality of a fishing gear, the legal origin of a product, among others.

However, after the scrutiny of 21 inspection report resolutions that had offenders identified (individuals and companies) for various violations, 100% of them have a fine.

Although this is the end of the administrative process, cases are likely to go to court, says lawyer García Soto, who in the past was in charge of the Legal Affairs Department of Conapesca.

“I can tell you what I can tell you from the point of view of a former public servant who was in charge of this type of responsibility at different times in the last 15 years and who currently dedicate myself in a very specialized way to litigation in this matter because it is not actually being sanctioned, that is, sanctions imposed are announced but they are not telling them later that these sanctions have fallen in court, when they are sanctions against a specific person,” he explains.

The Bill and the Trap

An inspector takes a tour in Tonalá, Chiapas, in southern Mexico. As you pass by the Southern Gas Station, you notice that in the maneuvering yard, a group of people unload plastic boxes from a trailer. The smell of seafood is intense. So decide to approach the driver with the inspection order.

“We went up to the box (of the trailer) to see what was on board, observing that it carried 140 jars of shrimp with fresh farm heads with 28 kilograms each jar, giving a total of 3,920 kilograms of shrimp,” explains the inspector in the minutes of May 20, 2021 as part of the resolution of file 100.2C.21/PA/CHIPS/066/2021.

As with drug trafficking, identifying someone responsible for transporting illegal fishing does not guarantee that there will be a sanction for those who head these trafficking structures.

When asking for documents that prove legal origin, the driver answers that he is only the driver and that the owner did not leave any documents. So the inspector retains more than 3 thousand kilos of shrimp.

The product was not claimed nor did it have the necessary documentation to prove its origin, so it was confiscated.

The General Law on Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture requires that the confiscation be put up for auction at public auction; sold directly; donated to social welfare or rehabilitation establishments; or destroyed if it is decomposed fish or prohibited fishing gear.

This same Act indicates that the product is accredited with the arrival, harvest, production, collection, import permit and fishing guide, as appropriate.

“To move the product they ask you for the fishing guide; and the fishing guide asks you for an invoice to request it, but the system that issues the guides does not verify the invoices,” explains a former inspector from Conapesca, who asked to keep his identity, for this report by Causa Natura Media.

Not carrying the documentation is not the only mistake that can occur. In places such as the Nueva Viga market, it has been found that the invoices do not contain necessary information such as a fishing permit.

In other cases, according to the former inspector, the merchant can partner with a company to obtain an invoice and make sure that the illegal product can be entered as legal and, subsequently, the issuer cancels that invoice. Even the Tax Administration Service (SAT) has fish marketers that appear on the list of billing companies.

“In the approaches we have had to the New Beam, what we know is that the information that must accompany the product based on arrival notices, fishing guides, etc., does not always travel with the product and therefore cannot prove the legal origin of the product. But in addition, there is no way for the information to accompany the product under the current circumstances,” explains Renata Terrazas, executive director of the organization Oceana Mexico.

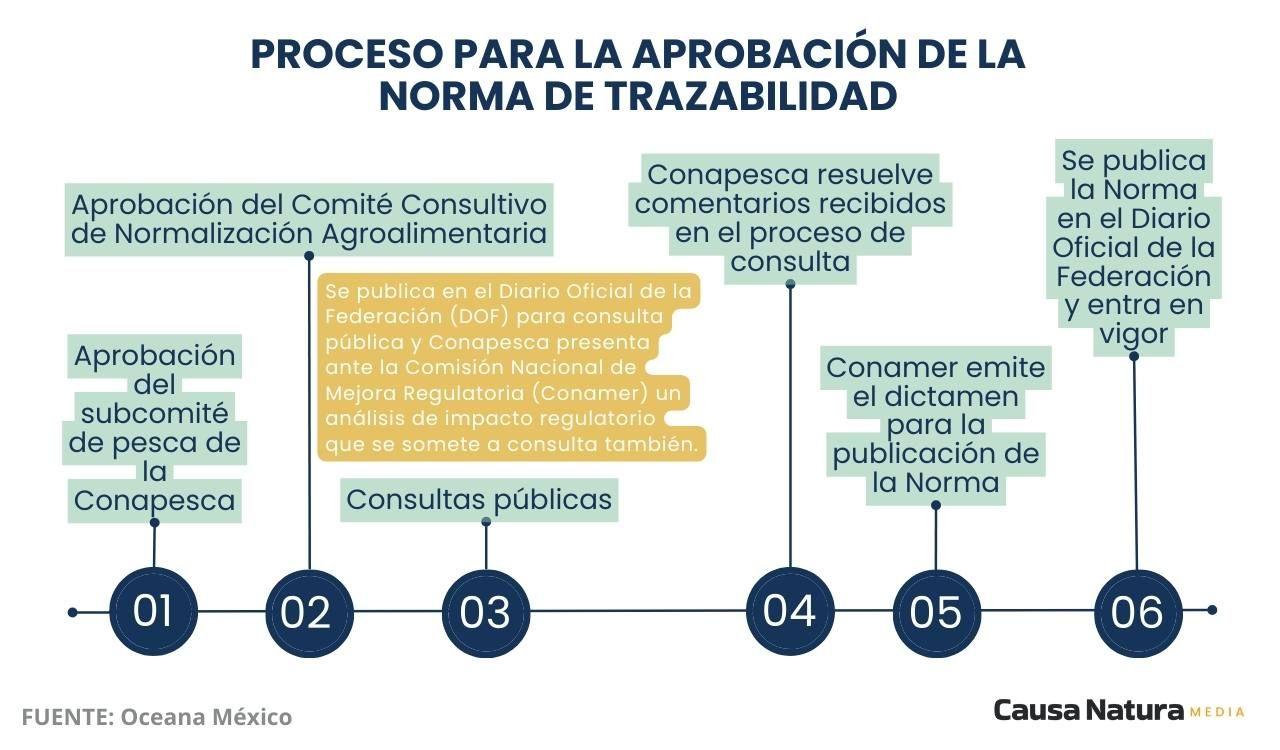

The civil organization has sought to promote a traceability standard to improve the information system and to ensure that documentation always accompanies the product from the moment of its capture to its commercialization.

There is currently a draft in Conapesca that is under arrest despite an urge from the Senate of the Republic for the institution to make progress in this regard. It proposes the creation of the Traceability System through an Official Mexican Standard.

However, it remains to receive the opinion of the Conapesca fisheries subcommittee, the first step towards its entry into force. Terrazas points out that this arrest indicates that “the fight against illegal fishing is not a priority for Conapesca”.

“Nowadays (the fish product) is accompanied by documents that we don't always know how they were constructed and if the information that feeds them is true or not and that also don't always accompany these documents to the fish,” Terrazas adds.

In addition to this, Conapesca's staff is not always enough and that inspections, as well as the budget and resources allocated, have been declining in recent years. The Causa Natura team found during a visit that there are two inspectors per shift assigned to the La Nueva Viga market, who were not present. When I asked the offices, it was said that they were in other proceedings and that they could only be found during the change of shift.

“Sometimes there's a fishing guide all over a truck and, if it's split up, the proper documentation to support the product is no longer done. The inspection and surveillance processes are very small compared to the quantity of product that arrives at the ports, but also that which reaches the New Beam. So the possibility of being arrested by an authority for not having the documents that support the legal origin of your product is very low,” explains the director of Oceana.

Causa Natura Media spoke with Roberto Gutiérrez Ambríz, president of the Board of Directors of La Nueva Viga, about the frequency of receiving fish and seafood without documentation or with invoices that do not provide all the information.

According to Gutierrez, market staff maintain a 24-hour review to review documentation, but they don't get involved in inspection and surveillance processes like Conapesca does.

“For us it is very important that they bring a recipient and that they bring the documents in order because it may be, and it has been our turn, that there are people who want to come and sell directly to our customers in our backyards. That's why it's important for us that they bring a recipient. Already what is applied in the law (the inspections) is Conapesca's turn,” says Gutiérrez Ambríz.

Domicilios, a game of hide and seek

Three Conapesca officers are holding in La Nueva Viga a vehicle from Tamiahua, Veracruz, with around 1,600 kilos of fish products transported in refrigerated boxes.

The resolution determines that he had incurred an administrative offense because the product was moved without the fishing guide. A fine of 8,000 pesos was imposed on the driver and it was decided to return the withheld product and property.

However, the commissioner to report the process was unable to do so at the Veracruz home, recorded in the inspection report. When the neighbors came, they stated that the accused no longer lived there.

According to García Soto, notifications are usually made by personnel from the legal affairs unit or assigned to state offices (formerly fisheries sub-delegations) or fishing offices.

Without being able to locate the driver, two years after the events, in August 2022, the notification of the resolution was made to him via platforms, which consist of a dashboard in the Conapesca offices and a website.

Cases like this in which there is no address in which to locate the person responsible take place automatically until a resolution is reached, even if the alleged person responsible does not show up. Once an identified person has been identified, Conapesca provides for sanctions, such as fines.

Although the case we present takes place in Mexico City and the fish product comes from Veracruz, an analysis by Causa Natura Media found that this also occurs in Yucatán, Baja California, Michoacán, Colima, Oaxaca and Sinaloa. These are at least 12 other cases, of the 288 analyzed for this investigation, where the defendant's home could not be identified.

Addresses were found that lead to vacant places, others where the person never lived, or the address is wrong or the one who was found stated that he was not the accused, without the commissioner responsible for notifying the sanction being able to do anything about it.

Punishment of formality

Paying a Conapesca fine is a challenge when an offender is not registered with the SAT.

For fines to be effective, García Soto explained that not only a fixed address is needed, but also a tax address with a federal taxpayer register, so that the SAT can effectively collect the penalties corresponding to federal fines.

The Conapesca Rights, Utilization and Product Payment System “e5Cinco” requires offenders to submit a Federal Taxpayer Register (RFC).

“If today, due to the fact that someone doesn't register with the RFC, they go and commit a lack of fishing material, and just because they haven't registered, they can no longer be charged the fine,” García Soto explains.

Regardless of whether the fine is imposed, there is an obstacle to charging when people are not in good standing.

“Forget if it is imposed, if it is not imposed. If from the design of the scheme they don't have such data, it will mean that in the end, when you have run all the machinery, that you had to have a budget, you had to have staff, you had to be in the moment, arrive with the sailors, draw up the record, send it to the lawyer, that this time if they wanted to do the process, that if they found the one they had to find, that this time they were so brilliant that if they hold the sanction in court and when they send it to the SAT I would return it to you saying: 'I'm sorry because the RFC doesn't come tax address, it's uncollectible and it's over because you can't do anything there anymore'”, he adds.

In this way, the requirement excludes informal fishermen from paying fines.

Data from the National Employment and Employment Survey (ENOE) show that the employed fishing population in the second quarter of 2023 amounted to 269 thousand people, of whom 86.6% are in the informal sector and 13.4% in the formal sector.

The former have an average monthly salary of 5,650 pesos and the latter of 8,210.

“It is clear that only the organized sector can be sanctioned there, that is, the one that has a permit, the one that has a fishing concession, which therefore has an address that is registered in the federal taxpayer register, that has a tax address and a tax box and who is a person who acts in the formality, not only of fishing but in the formality that contributes through the payment of taxes,” said García Soto about the sanctions scheme in Mexico.

These obstacles to paying fines affect the institution's ability to collect. In accordance with Article 144 of the General Law on Sustainable Fisheries and Aquaculture, these resources must be allocated to inspection and surveillance programs.

García Soto points out that “the authority can report that it imposed 150 sanctions this semester”, but if they are not charged, they are only “happy reports”.

Regarding the sanctions of Conapesca, Alejandro Olivera, representative in Mexico of the Center for Biological Diversity, points out that it is necessary to strengthen the legal area of the institution and that other sanctions be used in fishing matters, such as the cancellation of permits or the confiscation of boats that are rare and not only the fine should be used, which, as was evident, are difficult to collect.

“There are many sanctions in fishing matters involving the cancellation of a permit, the confiscation of boats, when have you heard that someone has their permit taken away for doing an illegal activity? It is not exercised, the few sanctions that exist in the law of aquaculture and fishing are not exercised, so you have to give an example, you have to put order, start setting an example and it doesn't happen,” he explains.

During 2022 and up to June 2023, 374 boats and 731 vehicles were precautionary seized, according to open data from Conapesca, however, in the same period, it issued 1,699 resolutions, of which only 120 consisted of the confiscation of assets, corresponding to 32% of the vessels retained as a precautionary measure, according to information obtained through the National Transparency Platform (PNT).

There are organizations, such as Cemda, that insist that before dealing with the sanctioning process, it is important to look at legal harmony so that the sanction can be imposed.

“If you don't address the underlying problems, then it's unlikely that what you do above will have the expected result or impact. In that sense, what we point out is, first strengthen your regulatory framework, align, link, harmonize, standardize with other instruments and plans in the field, and then start from there,” says Gómez Villada, marine biologist and coordinator of the research area at Cemda.

A sea of precariousness

“Right now they owe me since June, July, August and what is September. And to other colleagues I am sure they owe them more. They owe us what we call 'field expenses', which are 250 pesos a day for 20 days, that's 5,000 pesos a month, they are food support,” said an inspector interviewed for this report, who asked to keep his identity.

Although the concept is food support, inspectors say that they also use part of this budget for other expenses such as lodging and possible transportation contingencies.

One of Conapesca's main problems is that its budget is falling and, as a result, the amount allocated for inspection and surveillance.

While in 2015 the allocated budget was 3,513 million pesos, by 2020 it fell to 659 million, and in 2022 it only rose to 2 billion.

“It's paradoxical because it's a super important sector at the national level in economic, social and historical terms. Fishing, therefore, is a very important activity in the country and because it also receives, let's say, this lack of attention in terms of budget, because of course it also increases this vulnerability of the sector,” says Saraí Gómez Villada, marine biologist and coordinator of the research area at Cemda.

On the other hand, inspection and surveillance actions, which include inspections, land and water routes, and checkpoints, while in Enrique Peña Nieto's six-year term they reached 31,000 per year, by 2022 they only reached 25,506.

When comparing the first four and a half years of the current six-year term with those of President Enrique Peña Nieto, the decrease in the number of people placed at the disposal of the public prosecutor's office is -880%, of smaller vessels -98%, of larger vessels -187% and of engines retained by the authority -145%.

In the same way, there are states such as Puebla, Coahuila and Zacatecas that have not had any inspectors assigned in recent years, according to information obtained through transparency.

While in Guerrero, Oaxaca and Colima there are only three for the entire state. The states with the highest concentration of inspectors are Baja California, mainly due to efforts to protect vaquita marina, with 15, and Sinaloa with 36.

“At La Nueva Viga we have found that there are quite competent Conapesca personnel who seek to do their job in a good way. It's something you don't always see and it's worth recognizing. What happens is that for them to act they have a lot of obstacles,” says Renata Terrazas, executive director of Oceana.

Technologies against the crisis

Interviewed for this report, they pointed out that the use of technologies can help authorities to control illegal fishing from its source.

The Satellite Tracking and Monitoring System for Fishing Vessels (Sismep), which is a Conapesca instrument where you can check the movement of ships, their travel routes and identify if they fish in restricted areas, as well as provides information to safeguard human life at sea and to monitor meteorological phenomena.

However, it does not currently provide information in real time and requires deep-sea fishing boats to carry GPS.

To have more control over fishing activities, it is necessary to require that smaller vessels are also monitored and this information is available in an open and transparent way, says Alejandro Olivera.

In this way, all vessels would be identified and it would be known in real time when any one incurs a violation, so more information would be provided to fishing officers when drawing up an inspection report and would speed up Conapesca's administrative sanctioning processes.

Technology can also shield the commercial chain. Having a traceability system would allow the authority to consult the product in an electronic system and obtain all the information regarding the fishing permit, the arrival notice, the fishing guide, and to be able to detect if its origin is legal or not, Terrazas de Oceana said.

For her, the objective of this system is not to evaluate inspection and surveillance tasks, but to promote the generation of information that can be accessed by the authority to do their work, and in this way the irregularities that occur with the invoices could be corrected.

“The traceability system should make it easy for the authority to identify if that product is supported by the necessary documentation yes or no; with a chain of information that allows the authority to detect if there was manipulation of the information, if something happened that should not have happened,” he explained.

*This work had the collaboration of journalist Lilia Balam.

*This is the second report of the Paper Infractions investigation published by the Causa Natura Media journalism team. You can check the first one at this link .

Comentarios (0)